The Zong Massacre Trial

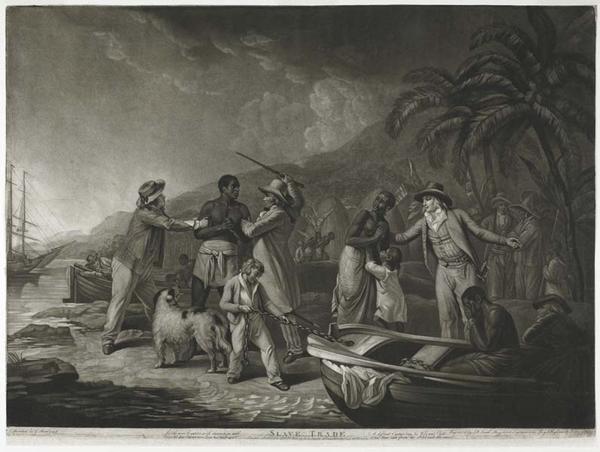

In 1781, British enslavers killed 130 enslaved Africans by throwing them off the ship Zong. The murders were the result of a cruel trade, made possible by London’s insurers.

Guildhall

1781–1783

A replica of the Zong, an 18th-century enslaver's ship, sailing past Tower Bridge.

This page contains content some people may consider sensitive, or find offensive or disturbing. Understand more about how we manage sensitive content.

Insuring murder

As the ship Zong sailed from west Africa to Jamaica in 1781, sickness spread among the crew and the roughly 470 enslaved Africans they held onboard.

Worried about their profits, the crew threw 130 of the Africans into the water, killing all of them. The enslavers had insured their “cargo”, so they claimed compensation for the loss.

That claim was challenged by the insurers in a London trial, which spread word of the massacre. Anti-slavery campaigners used the case to highlight the brutality of treating people as goods. But nobody was ever prosecuted for the murders.

Coming 20 years before the British trade in enslaved Africans was abolished, the Zong Massacre and the following trial shows us how the trade relied on London’s insurers, and the cruel calculations it produced.

The massacre happened at the peak of the trade

British traders began trafficking enslaved Africans in the 16th century. By the 18th century, Britain was the biggest trader of enslaved Africans. Ships left from Bristol, Liverpool and London, but London was the financial and insurance hub which made it possible.

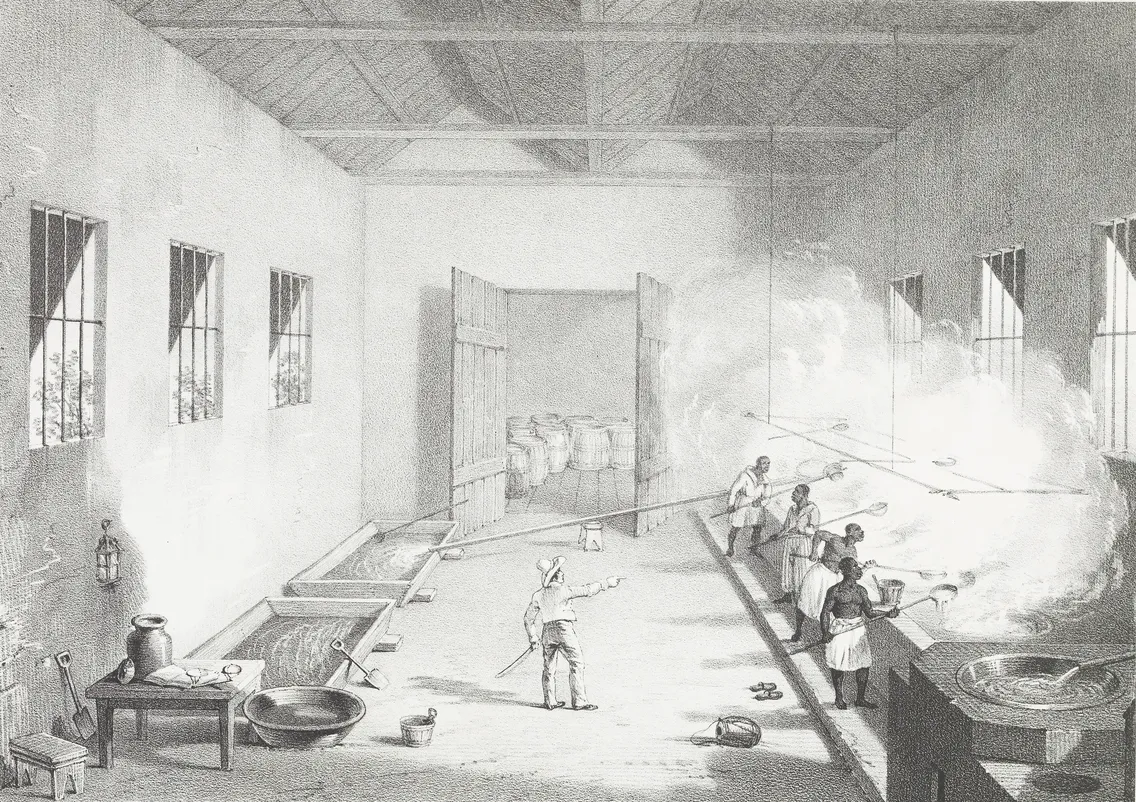

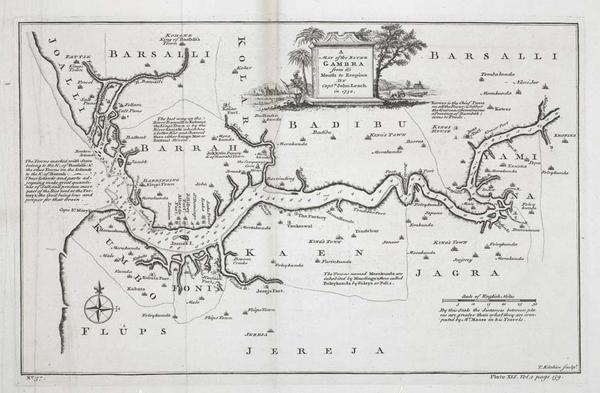

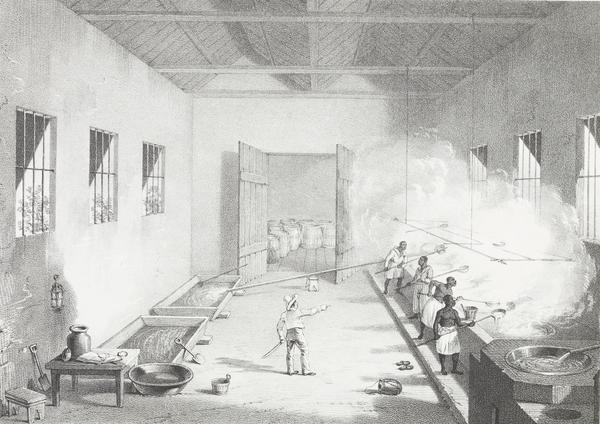

British slavers purchased enslaved Africans in west Africa. They then sailed to the Caribbean or north America, where enslaved people were sold to work on plantations.

Thousands of tonnes of sugar, cotton and tobacco produced by the labour of enslaved Africans came to London, requiring huge docks and warehouses to handle it.

The Zong’s journey

The Zong was a British-owned ship. In August 1871, it left Ghana in west Africa and headed for Jamaica.

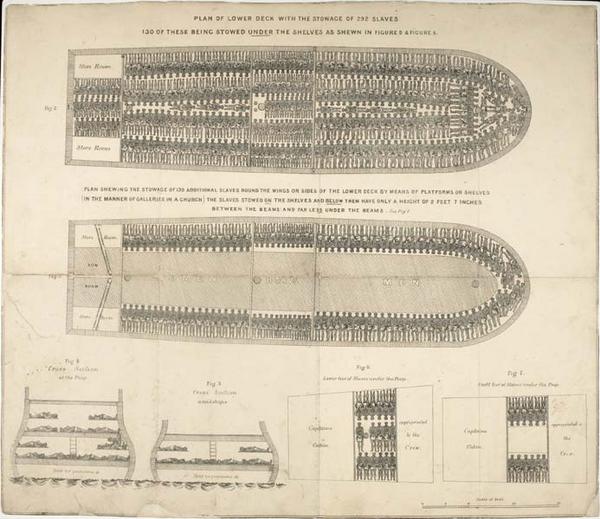

The ship was carrying around 470 enslaved people held in terrible conditions, controlled by a crew of just 17. It was twice the number the ship was designed for.

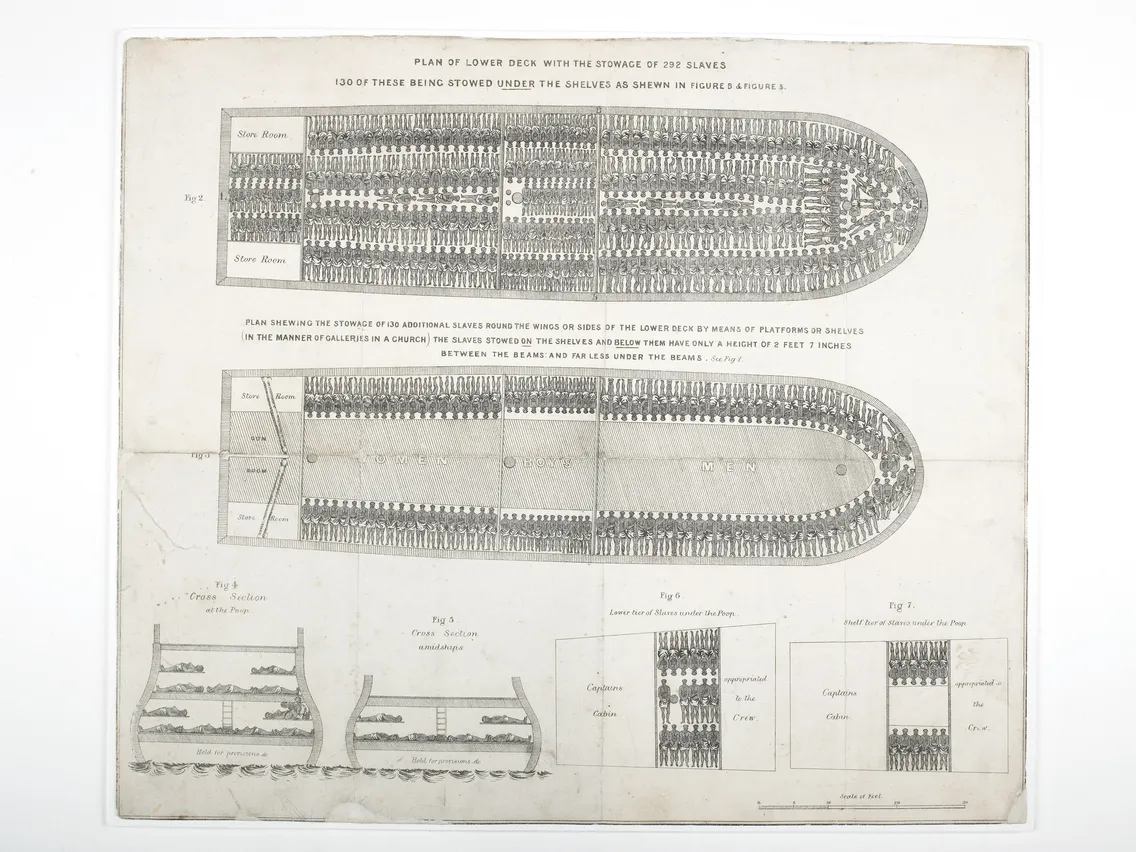

The plan above shows a Liverpool slaver’s ship and the regular level of crowding during the weeks-long journeys. Men were shackled below deck for most of the journey. Recalling his own journey as an enslaved person, Olaudah Equiano described “the loathsome smells… the chains… the filth… the shrieks of the women and the groans of the dying”.

The massacre

Weeks into the trip, 60 of the enslaved Africans had died of sickness, plus seven of the crew. With the illness spreading, more were predicted to die.

The ship’s master, Luke Collingwood, knew that if the enslaved Africans died of natural causes before they could be sold, they wouldn’t make as much money.

But their insurance policy covered emergencies. If enslaved people were thrown into the water to “protect” the safety of those onboard – the crew and owners could be paid compensation.

Over three days, 133 enslaved people were sent to their deaths. The ship’s crew later claimed that their drinking water was running out, an emergency which they said threatened the whole ship.

“a large part of the insurers’ profits came from enslaver’s journeys”

The insurance trial

Enslaved people were treated as “cargo” by their enslavers. It was normal for them to be insured in case of storms or other accidents. But this time their status had been used to justify mass murder.

When the Zong reached Jamaica, and news of the massacre got back to Britain, the ship’s owners claimed compensation.

The insurers refused to pay – accusing the owners of fraud and challenging the story that the ship had run out of water. A trial was held in March 1783 at the Guildhall in central London to settle the dispute.

The ship owners won the first case, but the verdict was appealed. A second trial seems to have never happened, meaning we don’t know how the case was settled.

Did the Zong Massacre help end slavery?

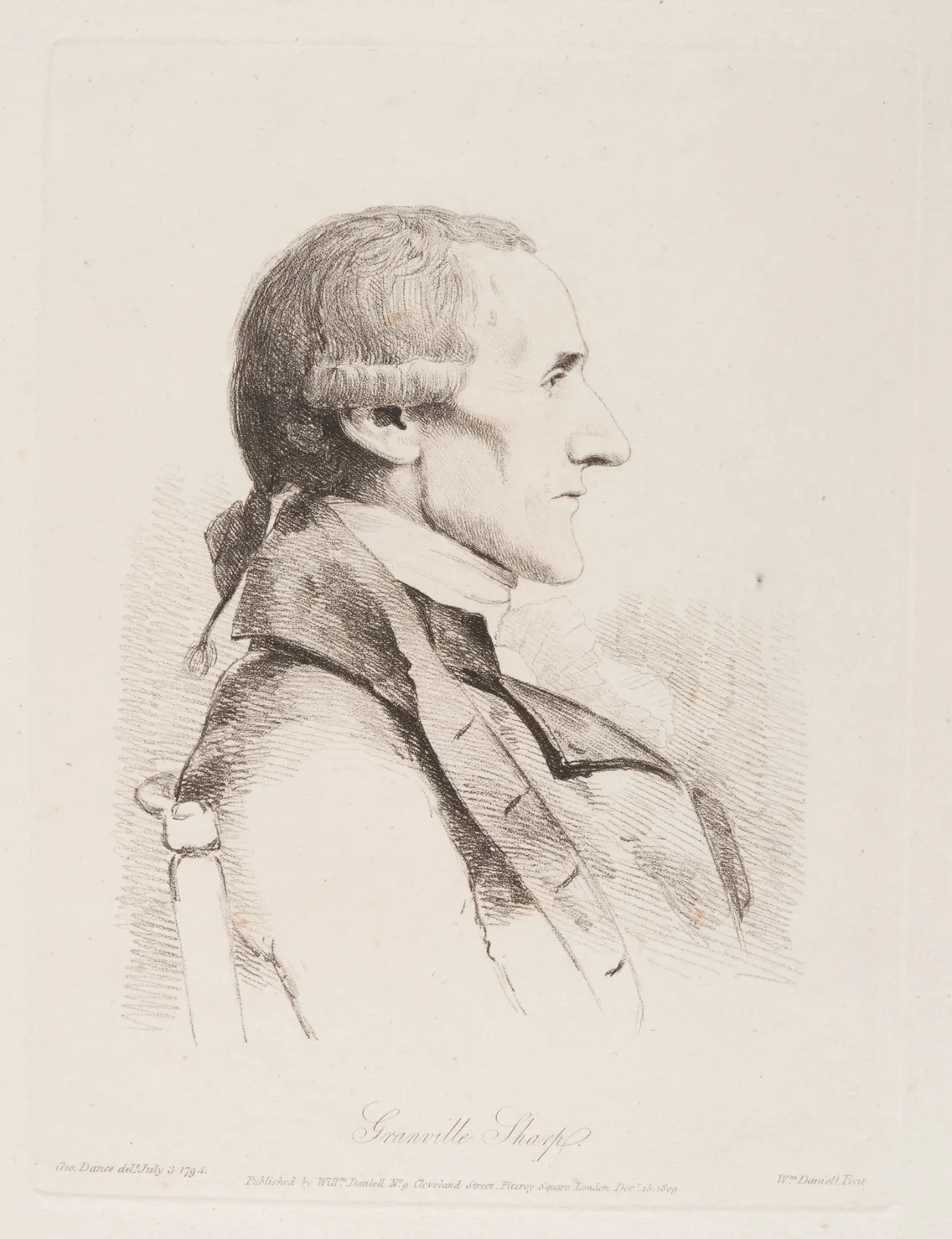

News of the trial spread to campaigners who wanted to abolish the trade in enslaved Africans, including Olaudah Equiano and Granville Sharp. Sharp wrote to the prime minister asking for a murder trial.

They never got one. None of the murderers were ever prosecuted. But the obvious brutality of the massacre did help anti-slavery campaigners, including formerly enslaved people, win support for their cause.

Their efforts, plus resistance by enslaved people, eventually made change.

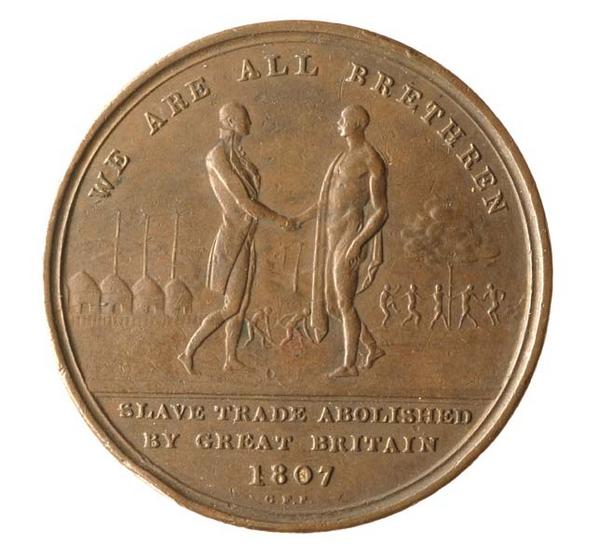

In 1788 the first regulation of the trade in enslaved Africans was passed, limiting the numbers a ship could carry. It took until 1807 for the British trade in enslaved people to become illegal, and until 1833 for a law to pass freeing all enslaved people in the British empire.

How London insurance made the trade possible

Long sea journeys have always been risky business. For traders of any kind, insurance was the way to reduce those risks.

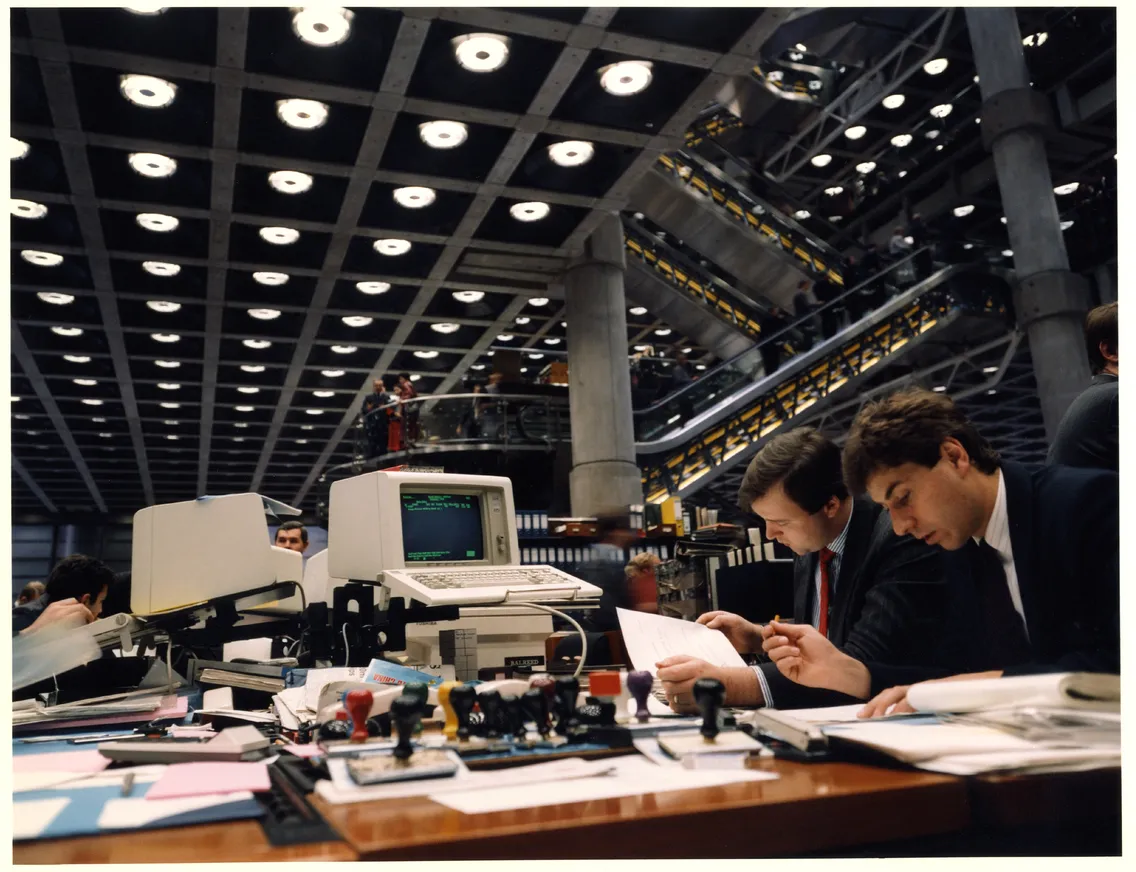

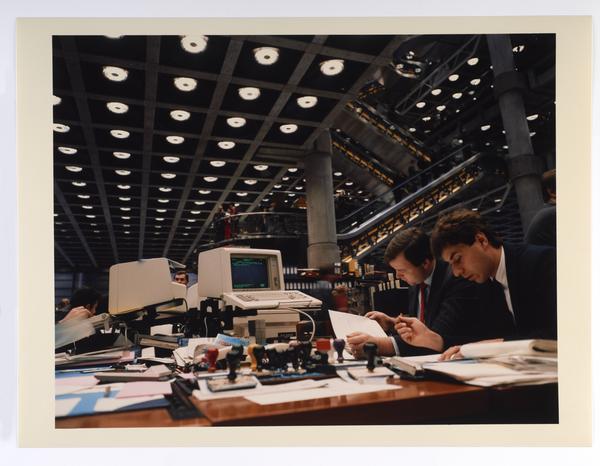

As international trade increased in the 17th century, London developed a sophisticated insurance industry to support it. This was centred around Lloyd’s insurance market, started in a central London coffeehouse in 1688. By the 18th century, a large part of the insurers’ profits came from enslaver’s journeys.

London’s financiers were equally involved, providing essential funding. Overall, a significant portion of the city’s wealth in the 18th-century was in some way connected to the suffering of enslaved Africans.