Women’s toilets & the fight for the right to work

How a roll of commemorative toilet paper tells a hidden story about women's rights, including workplace discrimination and just being able to leave the house.

1800s & 1900s

Standing up for their right to sit down

The lack of public female toilets in London was once a significant barrier to women's progress. It often restricted their ability to move freely around the city. They had no respectable option of going to the toilet outside the home.

The lack of toilet facilities was even used by employers as an excuse not to hire women. This lasted well into the 20th century.

To tell this story of women’s struggle for access to work and toilets, we can turn to one unassuming yet special object in our collection: a roll of commemorative toilet paper.

What a toilet roll tells us about women’s rights

The toilet roll was created in 2016 by the First 100 Years project to commemorate the journey of women in the legal profession over the past 100 years. It represents how women were often prevented from getting a job in the legal industry, simply because there were no female toilet facilities at law firms and legal institutions.

In 1919, the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act made it illegal to ban people from jobs based on their sex. But many businesses used excuses to avoid hiring women, notably that they couldn't adapt their workplaces to accommodate them.

“It represents the collective voice of those that faced such a ridiculous obstacle”

Dana Denis-Smith, First 100 Years

The founder of the First 100 Years, Dana Denis-Smith, said: “The artefact is a visual representation that we felt empowers women to share their own experience in a dignified but striking way. It represents the collective voice of those that faced such a ridiculous obstacle."

"Sitting comfortably? Thanks to the courage and tenacity of pioneering women in law, now we all can."

Access to toilets in Victorian London

There were inadequate female facilities throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. 'Respectable' women couldn't relieve themselves in streets or alleys as men did, and the few toilets available in Victorian London were overwhelmingly built for men.

Women who wished to travel into central London or even further for leisure and pleasure had to carefully plan where they could ‘stop off’ on the way. So excursions outside the house were often based on visiting friends and family, where toilet facilities could be guaranteed.

“Women were put on a leash as long as their bladder capacity”

Because of this lack of access to toilets, women were put on a leash as long as their bladder capacity. They were tied to their local area. Even when London's first public toilets were built for railway stations and the 1851 Great Exhibition, the common modesty of Victorian society assumed women would be too embarrassed to be seen entering them.

This was part of a broader Victorian pattern of dividing the city into a male-oriented 'public' sphere and a female-oriented ‘domestic’ one. Victorian society saw the ideal woman as being 'the angel of the house', naturally focused on being a good wife, mother, sister and daughter.

What changed in the early 20th century?

This unequal access to the public city began to be challenged in the 20th century.

In the early 20th century, women could spend more time out of the home at new places like Selfridges on Oxford Street.

The vast department store Selfridges opened on Oxford Street in 1909 – complete with its own toilets. Facilities like these within safe, respectable spaces like Selfridges was a game changer. They allowed women to spend more time away from home and away from their local area. As a result, shopping could be a leisurely and enjoyable activity.

Selfridges also benefited the Suffragettes, who spent a lot of time on the streets campaigning. They used department stores like this not just for the toilets, but also to rest and have a cup of tea in comfort

Women’s access to ‘war work’

The First World War was a catalyst for change for women’s employment. Working class women had traditionally contributed to family income. But the war brought middle class women into the workplace.

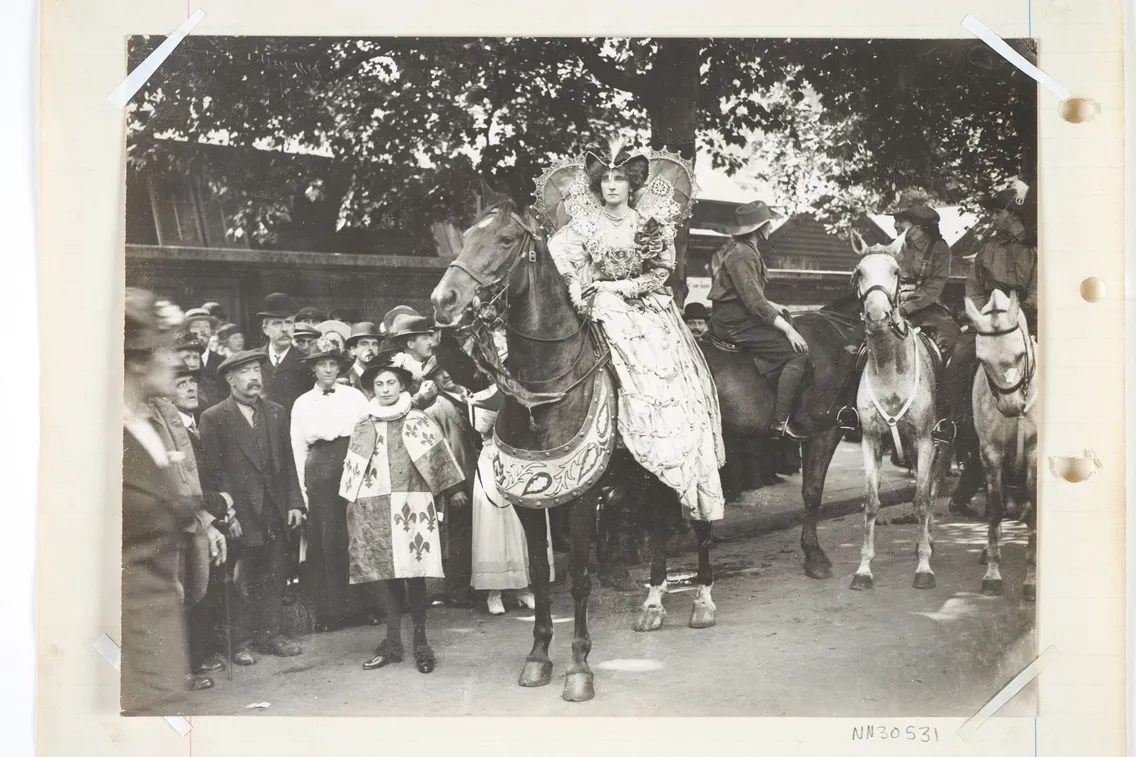

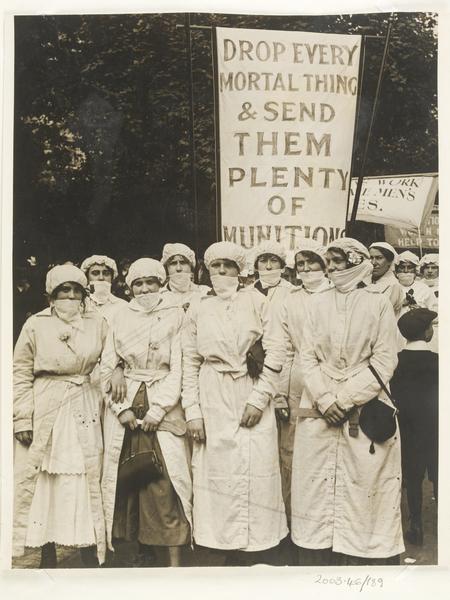

In 1915, Suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst organised the Women’s Right to Serve march in London where women were encouraged to register for ‘war work’. Women served on farms, railways, in the police and fire service, and as workers in munitions factories. War gave women many work opportunities denied to them in peacetime.

There was still widespread resistance to the idea of women doing large-scale war work. It was felt to be ‘unwomanly’ and also a threat to men’s jobs. As women were paid less than men for the same work, male-dominated labour unions feared that their men would be replaced with cheap female labour. Employers also saw providing dedicated female facilities, like changing rooms and toilets, as a burden.

But by the end of the war in 1918, 7.5 million women were working. Through work, many middle class women had become more financially and socially independent. Many didn’t want to return to a life of domesticity or just running the family household.

Women working in a munition factory.

Resistance to women in the workplace

This wartime shift in attitudes wasn’t to last. Throughout the 20th century, women still struggled to enter the workplace.

The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act in 1919 made it illegal to refuse a woman entry to professions because of their sex. It meant that women could now work in medicine and law, or sit on a jury.

But the act failed to outlaw the marriage bar, which was a regulation employers wrote into contracts that stopped women working when they married. The civil service and local government maintained a marriage bar. So married women couldn’t work as teachers, nurses and doctors.

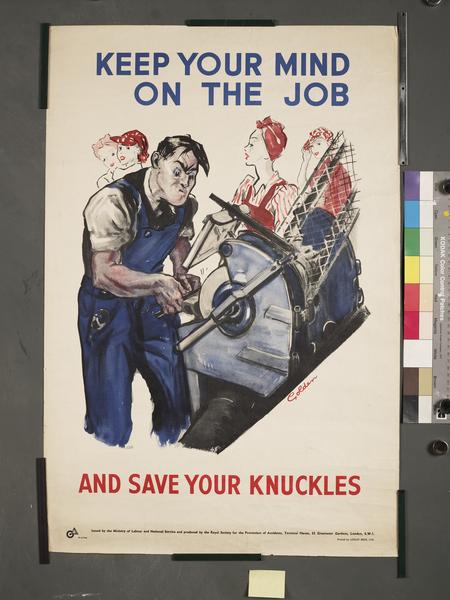

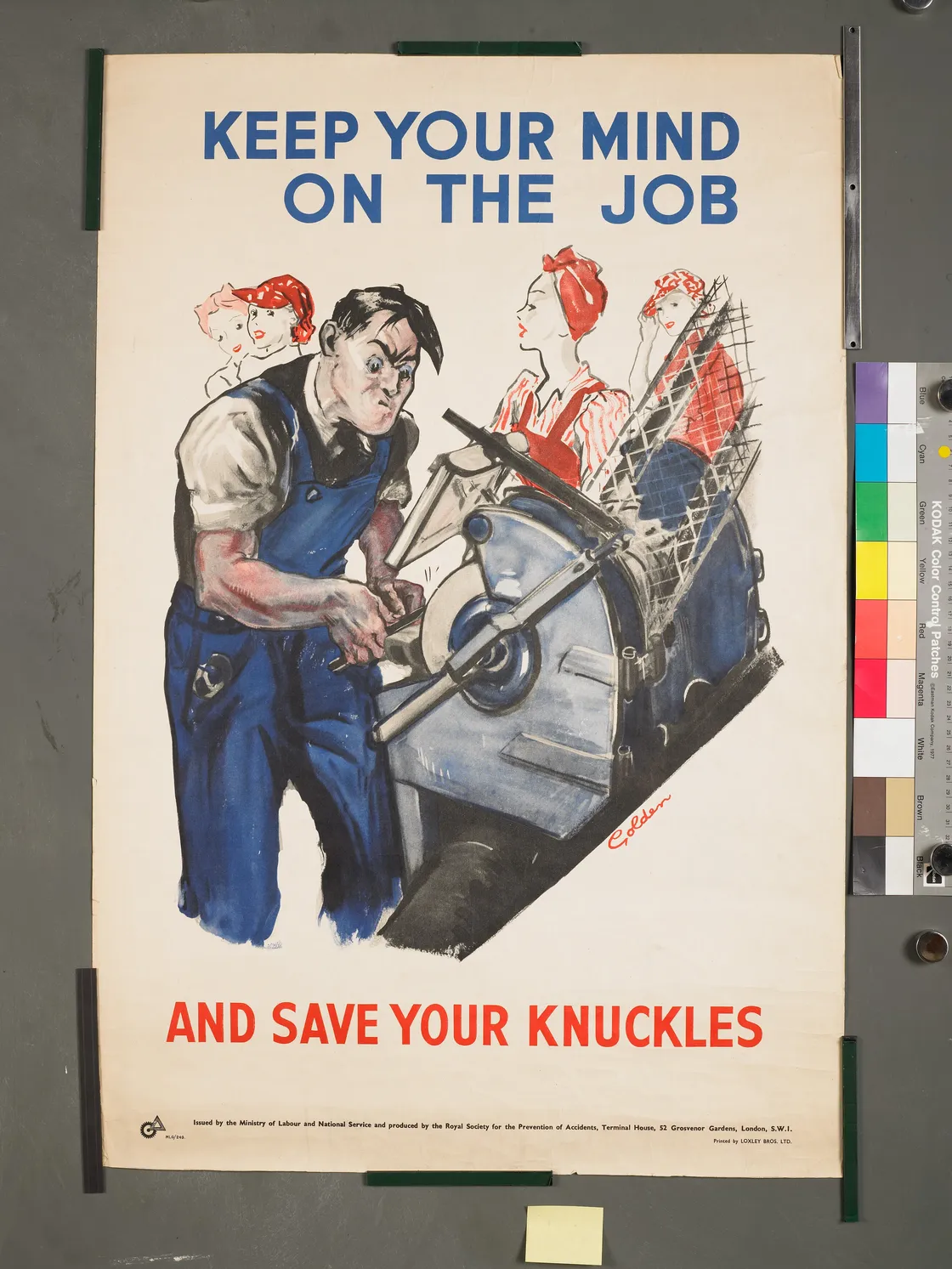

One of a series of 'safety first' posters produced during the Second World War in response to the growing number of women working in factories.

The civil service abandoned the marriage bar in 1946 – but it continued in other professions and government departments for decades after.

In 1970, the Equal Pay Act gave women the legal right to have equal pay for performing equal work to men. But they still continued to face lower pay and less rights than men in the workplace. They also faced difficult choices when juggling work with family responsibilities.

Women’s campaign for equality in the workplace

Both wars saw strikes by women employed in war work, campaigning for equal pay to male workers, but also for better safety equipment, recognition – and bathrooms. Employers were resistant to installing facilities for women, including toilets, and used this as an excuse to not hire women.

Turning back to our toilet roll, we can see how this movement for equality in the workplace continued throughout the 1900s. “As recently as the 1970s, lack of washroom facilities for women was used as a pretext not to hire female lawyers,” the printed text on the sheet reads. But it was the “perseverance” of “pioneering women in law that opened the way for many like-minded women to enter the legal profession.”

It wasn’t until 1992 when it became a legal requirement for employers to provide separate toilet facilities for men and women. And it was decades later, with the 2010 Equality Act, when transgender people had explicit protection against discrimination and the right to access single-sex spaces and facilities.

Researching credit: based on a blog by Alwyn Collinson