Witches, medicine & magic through London’s history

Amulets that protect you from plague? Witch-repelling bottles filled with nails and urine? Before the arrival of modern medicine, Londoners relied on all sorts of magic to keep them from harm.

Since the 1st century CE

Finding solace in the supernatural

Disease and death have always terrified Londoners – and rightly so.

Modern medical science and public health systems have enabled us to defend against plagues and pandemics. But the people who walked London’s streets before us had to rely on other resources as they tried to understand the overwhelming, awful nature of disease.

Whether it was carrying amulets or experimenting with alchemy and astrology, Londoners have long turned to various forms of magic for personal protection.

Magical amulets from ancient London

Some of the earliest examples of Londoners using magic come in the form of magical amulets. These were prepared by the people of Roman London against plagues and infectious maladies.

This amulet is inscribed with a protective spell or prayer to the gods, invoking their protection for the amulet’s owner, a man named Demetrios. Found in the River Thames, it may have been thrown there deliberately as a ritual offering.

Other magical Roman objects of this sort survive, including personal curses against specific individuals, presumably wishing some kind of personal or physical harm against them.

Pilgrim badges: where magic meets religion

Many of the ‘magical’ practices of the past would have been understood as matters of religious faith by their followers.

In medieval London, cheap lead badges purchased as souvenirs of holy pilgrimages were believed to hold magical protection against sickness. Many Londoners went on pilgrimages to the shrine of London-born martyr Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, in Kent’s Canterbury Cathedral, where he was assassinated in 1170.

“In everyday sickness, the badges must have been a comfort.”

The inexpensive, mass-produced pilgrim badges were touched against the shrine in order to absorb some of its holy power. After this, they were thought to hold healing and protective properties in times of illness.

In everyday sickness, the badges must have been a comfort. And during the horror of widespread plagues, such as the Great Pestilence of 1348–1350 (known as the Black Death), perhaps they were the only hope of beleaguered Londoners as they watched their fellow citizens die in their thousands.

Pilgrim badges relied on the principle of ‘sympathetic magic’, whereby physical objects could represent individuals with magical powers. In the case of saints and martyrs, their magic was a welcome aid in times of sickness. But the principle also applied when trying to protect against witches and other agents of harmful magic.

Protection against witchcraft

Belief in witchcraft in Europe reached its heights between 1450–1700 CE. Witch hunts killed perhaps 100,000 people via official execution, torture or illegal lynching. Religious powers were in constant battle against witches and the devil.

In England, witchcraft laws passed in 1542, 1562 and 1604 established witchcraft as a crime punishable by death. Witches – who were usually, but not always, women – were tried at court and accused of ‘maleficium’, causing harm by using magical spells

“The combination of human urine and iron nails was a popular one to fill the bottles”

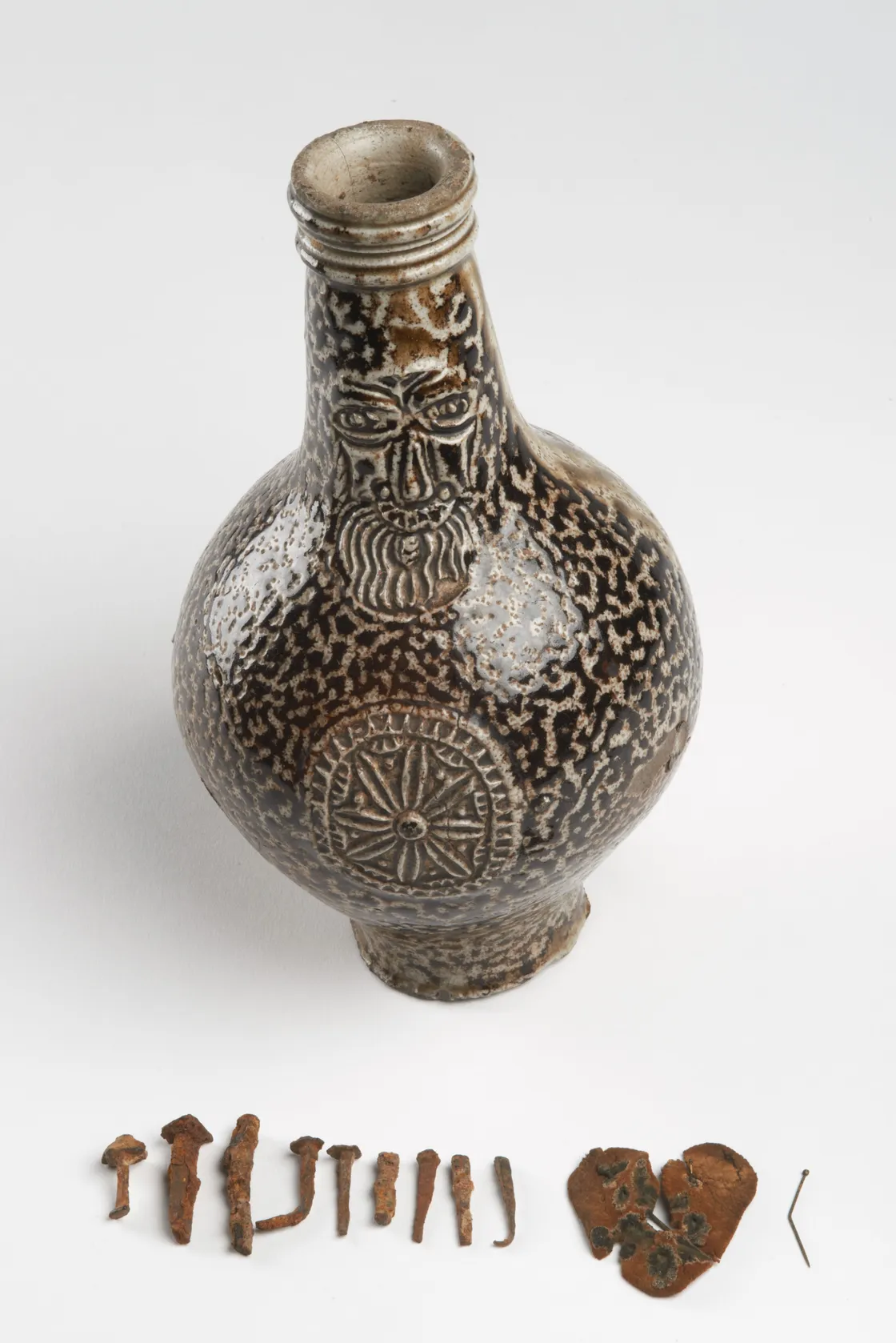

Witch bottles were everyday bottles or jugs filled with items believed to discourage witches, such as lead shot or bundles of hair. They’ve been found in London buildings from the medieval period right through to the 1800s. The combination of human urine and iron nails was a popular one to fill the bottles. It was based on the belief that the bottle would transfer its power to the witch and cause them to have painful urination.

This 17th-century jug had been re-used as a witch bottle and was found with a hear-shaped piece of felt, pints and 11 nails inside.

Shoes were also invoked for their protective qualities, because they would suggest to the witch that a living human patrolled the area. These boots were deliberately placed within the roof of the Savoy Chapel on the Strand as late as 1876.

The belief in witchcraft persists

Many Londoners became increasingly sceptical of witchcraft by the 17th century. But the belief never entirely disappeared. And the suspicion of witchcraft was never confined to impoverished or poorly educated people. The London diarist Samuel Pepys (1633–1703), who was a highly educated and influential figure, recorded conversations in which he and his friends shared their knowledge of protective charms and discussed other ‘enchantments and spells’.

As late as the 1680s, prosecutions for witchcraft were still taking place in London, with the accused generally on trial for causing the illness or death of an individual. In 1682, the Old Bailey heard the case of Jane Kent, indicted for witchcraft after supposedly bewitching a young girl named Elizabeth Chamblet. Chamblet died after reportedly falling “into a piteous condition, [with] swelling all over her body, which was discoloured after a strange rate”.

The distraught father, who’d previously argued with Kent over the unsuccessful sale of some pigs, blamed witchcraft for the inexplicable death of his daughter. Kent was eventually acquitted, after numerous people testified to her good character and her regular attendance at church. But Chamblet’s mysterious ailment was never deduced.

Elizabeth Sawyer, of Edmonton, Middlesex, who was executed for witchcraft in 1621.

The laws against witchcraft in England were eventually reversed with the 1735 Witchcraft Act. Practising witchcraft was no longer seen as a legitimate threat that was punishable by death. Instead, the new law assumed witches weren’t real and that practising magic was considered to be fake and deceitful. The accused would face imprisonment instead of execution.

Mixing magic and science

Magic and science also overlapped in early modern London. ‘Natural philosophers’ such as Francis Bacon and Nicholas Culpeper combined their studies of logic, medicine and botany with experiments in alchemy, astrology and fortune-telling. These were not regarded as incompatible practices. They were complementary efforts towards understanding the natural universe, with the human body at its centre.

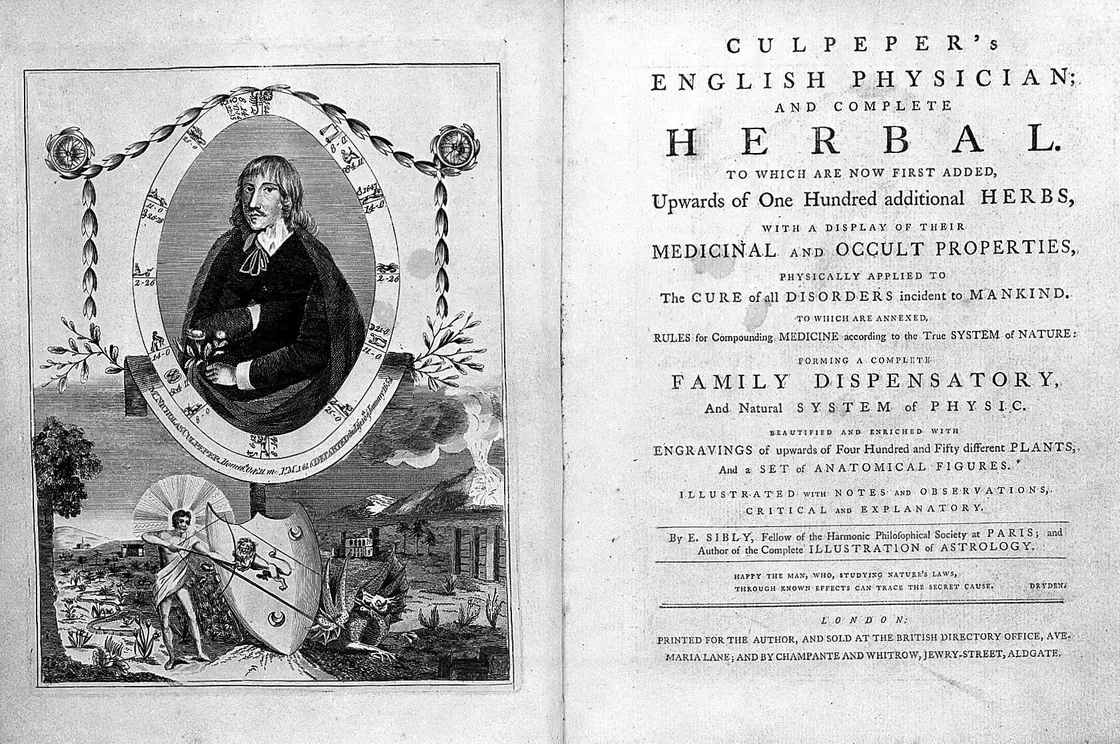

Culpeper played a key role in bringing medical knowledge to a wider audience. He ran an apothecary (or pharmacy) from his home in Spitalfields, outside the authority of the City of London. And he used astrological observations in his research into herbal medicine. In his 1652 publication The English Physitian And Compleat Herbal, he recommends collecting, preparing and administering plants under specific astrological conditions so that they’re more effective.

Nicholas Culpeper's The English Physitian And Compleat Herbal.

Even today, Londoners have not completely abandoned their belief in magic as a precaution against disease. Modern witch bottles are often picked up by mudlarks, people who have permission to search the shores of the Thames for objects from London’s past.

The modern ‘wellness’ industry, with its reliance upon detox supplements and crystals imbued with positive energy, is a new manifestation of our need to feel like we are doing something – anything – in the face of our own physical fragility.

Writing/researching credit: Danielle Thom