Who was the Suffragette Emily Davison?

Emily Wilding Davison is remembered as the Suffragette who died days after being knocked down by a horse at the Epsom Derby in 1913.

1872–1913

Davison's dash onto the racetrack was the last act in many years of militant protest.

Brave and independent to the end

Davison stepped onto the track during the race in a last effort to win women the right to vote.

Between 1906 and 1913, she repeatedly put herself in danger to draw attention to the Suffragette campaign. She often acted on her own initiative, without instruction from the campaign’s leaders.

Davison was celebrated by campaigners as a “martyr” to the cause, but we’ll never truly know what her intention was that day at the Derby.

Emily Wilding Davison was a teacher before she became a full-time militant.

Her early life

Davison was born in Blackheath, south-east London in 1872.

She studied English at Holloway College and St Hugh's Hall, Oxford – but as a woman, Davison was not allowed to graduate. She worked as a school teacher and a private governess, teaching children in their home.

Emily Wilding Davison, second from the right, with other Suffragettes.

Becoming a Suffragette

Suffragettes were followers of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), a militant campaign group founded in 1903 and led by Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst.

In the years up to 1914, Suffragettes used law-breaking tactics to demand votes for women. They began with peaceful marches, but later attacked buildings by starting fires and smashing windows.

Emily Davison became a member of the WSPU in 1906. She was 34 years old then, and working as governess to the children of Francis Layland-Barratt, a Liberal MP.

After 18 months, her urge to embrace her militant identity led her to resign.

“Davison often chose her own unique and risky ways to protest”

An independent campaigner

Davison became a full-time campaigner for the vote in 1909, but she was never formally hired as a paid WSPU Organiser.

Davison often chose her own unique and risky ways to protest, including hiding in the House of Commons three times. In 1911 she was the first Suffragette to set fire to a postbox – something which went on to become a frequent tactic.

Prison time

Davison went to prison eight times for offences including stone throwing and assaulting someone she mistook for the Chancellor David Lloyd George. You can see her being arrested in a photo in our collection.

Our collection also features many examples of the Holloway Brooch and hunger strike medal which Suffragette prisoners, including Davison, received from the WSPU for their commitment to the cause.

This WSPU poster shows the force-feeding of Suffragettes who went on hunger strike while in prison.

Like many Suffragettes, Davison used hunger strikes to protest while in prison, and was force-fed by the authorities – a violent process where a rubber tube was forced into her mouth or nose.

In 1909, she barricaded herself in her cell at Holloway Prison as another protest. A prison warden forced a hose into the cell and showered her in ice-cold water.

And while serving her final sentence in London’s Holloway Prison in 1912, Davison protested the constant force-feeding by throwing herself over some railings and onto a staircase below. She was knocked unconscious.

How did Emily Wilding Davison die?

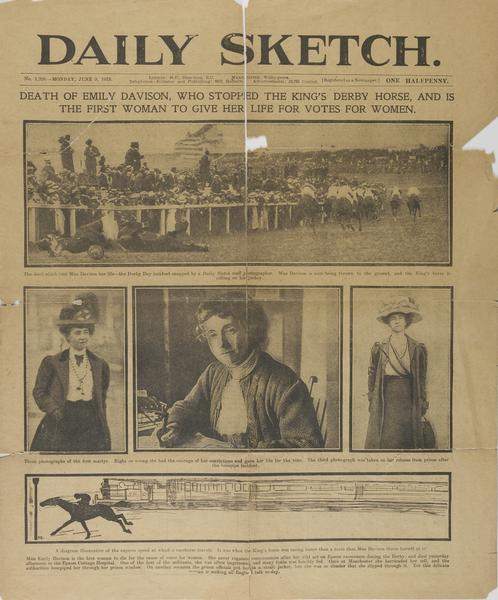

On 4 June 1913, Davison ran onto the racetrack during the Epsom Derby. She collided with a galloping horse owned by King George V, causing her severe head wounds and injuring the jockey.

Davison died four days later in hospital, surrounded by distraught Suffragettes.

What was the reaction?

The collision was captured on film and almost immediately became an infamous event in British history.

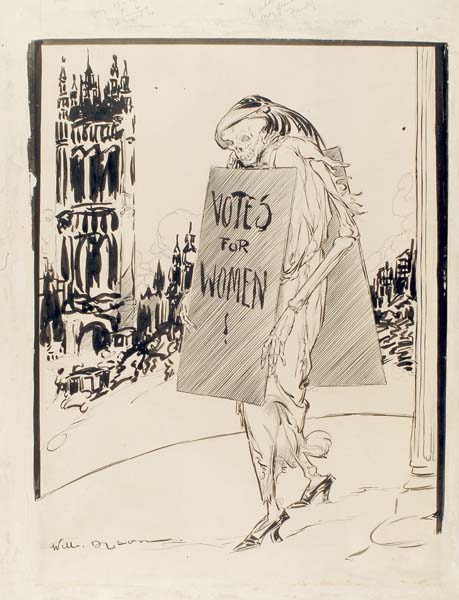

A cartoon in our collection from the Daily Herald by William Dawson shows Davison as the victim of the government’s refusal to give women the vote. But the public reaction was mixed. Davison also received hate mail while in hospital.

The WSPU stood behind Davison after her death. They claimed her as the first Suffragette martyr, praising her “noble sacrifice”.

Davison's funeral procession drew large crowds.

But Davison probably didn’t mean to sacrifice herself. She purchased a return train ticket on Derby day, suggesting that she hadn’t intended for her protest to result in her death.

The WSPU organised a funeral procession for Davison. 5,000 women from all over Britain gathered in London. They carried banners reading “Fight On and God Will Give Victory”.