The Whitechapel Fatberg

In 2017, a stomach-churning discovery was made in a sewer below Whitechapel – a monster fatberg, a 250-metre long, 130-tonne mass of oil and wet wipes.

Whitechapel, east London

2017

A surviving sample from the Whitechapel Fatberg.

A world-famous blockage

After the fatberg was removed, a sample came to London Museum for a world-first display in 2018. It’s now part of our permanent collection.

The story created interest worldwide – with newspapers, TV stations and the public equally fascinated and revolted by it.

The fatberg is a monstrous product of Londoners’ lifestyles. It’s a foul reminder of the hidden systems which keep the city clean. And it’s a potent sign of the pressure our infrastructure is under.

Most of London’s sewage network was built over 150 years ago. To keep London clean and Londoners healthy, the city will need new solutions. But we must also know the impact of what we throw away.

Discovering and displaying the Whitechapel Fatberg

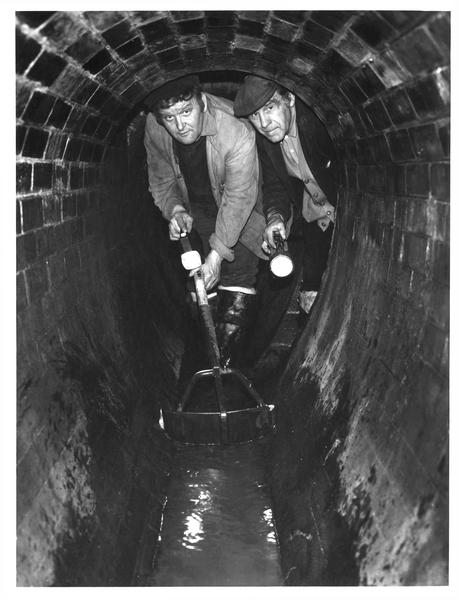

During a routine inspection in Whitechapel, east London in September 2017, Thames Water workers stumbled upon a gigantic solid blockage which was threatening to cause flooding.

“The blockage inspired a drag performance”

Fatbergs had been found before. But this was larger than any other. It was over 250 metres long – about the length of four football pitches, or the same as Tower Bridge. It weighed an estimated 130 tonnes, about the same as 11 double-decker buses.

Its discovery and display in the museum were a sensation – the fatberg was covered by the New York Times, CBS, Sky News, ABC Australia, Al Jazeera, every UK national paper and the BBC. The blockage inspired hundreds of millions of tweets, a musical, a drag performance and a cake replica.

The Whitechapel Fatberg was a gruesome discovery.

What is a fatberg?

A fatberg is mainly made up of cooking fat, wet wipes and other sanitary products. When these are flushed down toilets or tipped down drains, they can congeal together, making a solid mass that causes a blockage.

The term “fatberg” was first used to describe rock-like lumps of cooking fat washed up on a British beach, but was adopted by London sewer workers and entered the Oxford English Dictionary in 2015.

What made this fatberg so giant?

The British diet has changed in past decades, becoming oilier. We also no longer see value in keeping or recycling oil. So more fat is ending up in our sewers. Lipids from hair conditioners and other cleaning products make the problem worse.

More people are also flushing waste that the sewer system isn’t designed for. Poo, pee and toilet paper are all our pipes should handle, yet non-degradable wet wipes frequently end up getting flushed. Wet wipes created the main structure of the Whitechapel Fatberg.

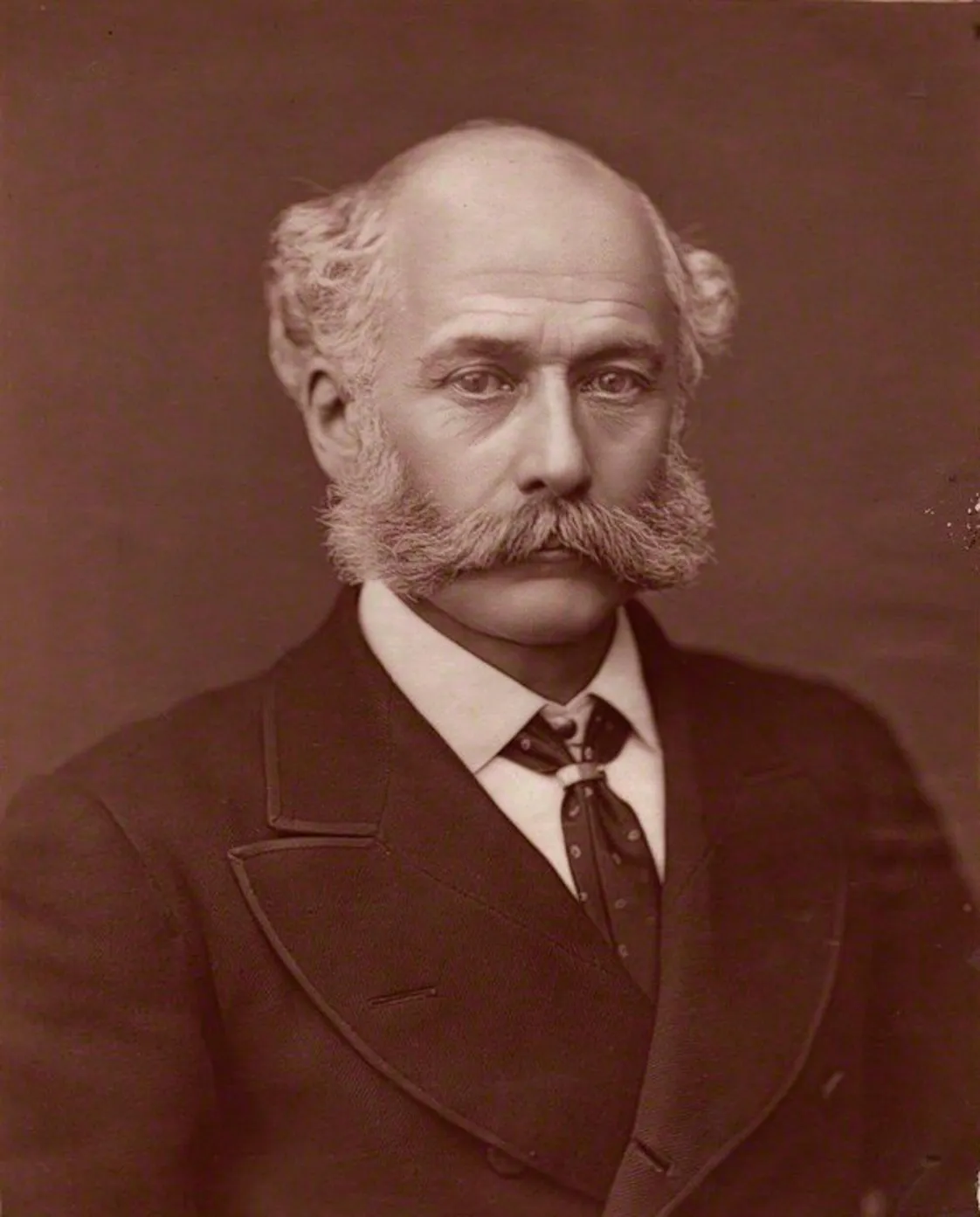

London’s rising population adds to the problem. The city’s sewers were built in the 1850s, following a design by Joseph Bazalgette. Although he planned for a growing city, London’s population has rocketed far beyond what he accounted for.

London’s super sewer

The 2021 census recorded 8.8 million people in London. That’s 626,000 more than just 10 years before. And the population is expected to continue growing. Without changes to London’s sewers, or unless Londoners change how they get rid of waste, there will be even more problems in the future.

The new 25km Thames Tideway tunnel – dubbed the “super sewer” – stretching from west to east London, is one answer. This huge project is designed to prevent waste being dumped into the Thames after heavy rainfall, something which previously happened regularly.

What happened to the fatberg after it was discovered?

At the press conference announcing the Whitechapel Fatberg’s discovery, we asked for a piece for London Museum. Thames Water agreed.

Workers began breaking up the fatberg. They used shovels and high-powered jets of water to clear the blockage, and sucked it up to the surface with a hose.

Small samples have ended up in our permanent collection. And the rest of it? Most was destroyed, but some was turned into biodiesel at a site in the north-west of England.

“We saw life emerge from the fatberg”

Samples from the Whitechapel Fatberg were put on display at London Museum.

How was it preserved?

We were the first museum in the world to take, display and conserve a fatberg. We didn’t even know if it would survive.

When the fatberg was pulled out of the sewer, it was dangerous – full of bacteria and releasing toxic gases.

We decided drying the fatberg was the best way to put it on display. The piece in our collection was dried at the Thames Water depot at Beckton in Newham before coming to us.

How has the fatberg changed?

The fatberg lost weight as it dried. It became harder – more like the stuff you find stuck to sewer walls.

After being placed in a case, the fatberg began to sweat, releasing more of its moisture. As its moisture levels changed, so did the colour of the fatberg – from dark brown, to pale grey, then to a darker beige.

We saw life emerge from the fatberg. Inside its sealed case, mould grew. Flies hatched too, before and while on display. It’s likely these were Phorid flies, also called coffin flies, which feed off decaying matter.

The flies have now gone, and the fatberg is slowly shrinking.

Research credit: Vyki Sparkes, Curator (Social and Working History)