What were penny toys?

Sold by street traders in the City, these children’s toys were some of the first that poorer London families could afford.

City of London

Late 1800s & early 1900s

Little novelties sold on the cheap

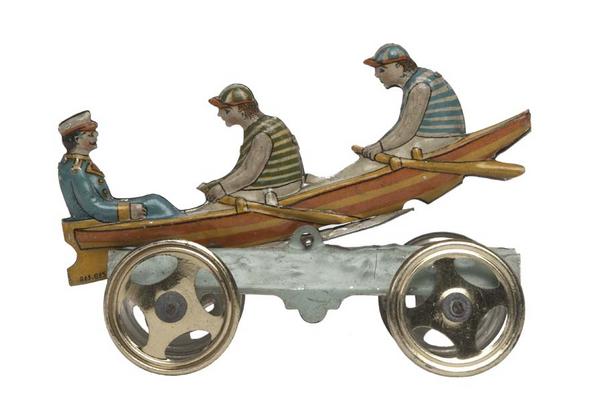

Penny toys were small, mass-produced children’s toys that were sold for one penny. They were made out of lots of different materials, including paper, wire, wood and tinplate. Sometimes they were used as containers for sweets or candies. And often they had little mechanisms with which you could make the toys move.

London Museum has over 1,500 penny toys and novelties purchased by an Islington-born man named Ernest King between 1893 and 1918.

These toys give us an insight into the history of London at a period of great social change. They also shine a light on the life of the street sellers – some of the city’s poorest citizens – who traded them.

Ernest King’s collection of penny toys

King worked as a company director for the straw hat maker Melch and Sons. Based at the firm’s headquarters in Gutter Lane, City of London, he was well placed to observe the activities of the many ‘gutter merchants’ trading in the nearby St Paul’s and Ludgate Circus area. These were men, women and children who stood just in the road by the kerb or ‘gutter’ selling a range of penny toys and novelties from trays hanging from their necks.

Penny toy of a school pupil at a desk, used as a container for sweets or candies.

When he was 25 years old, King began buying toys from these street sellers. He continued this tradition for a further 25 years. His collection is full of miniature figures and models covering a range of subjects, including politics, war, royal memorabilia, transport and popular culture.

His collection is full of miniature figures and models

In 1918, King donated his collection to the museum. He also gave us two notebooks listing all the objects and their date of purchase, and a scrapbook filled with news cuttings reporting the plight of the street sellers. King’s collection, combined with this additional information, allows us to chart the interests, concerns and popular trends affecting Londoners and London at a very specific moment in time.

How the toys came to London

London was a major market for tinplate penny toys that were primarily made in Nuremberg, Germany. The main distribution point for imported German toys arriving at London's docks was the Houndsditch area on the edge of the City. Bavarian agents working on behalf of companies like Meier and Fischer would set up wholesale warehouses here.

Mechanical toy carousel manufactured by Johann Phillipp Meier in their factory at Nuremberg, Bavaria.

Tinplate penny toys were particularly popular between the late 1890s and early 1900s. But trading with Germany was halted by the arrival of the First World War in 1914.

Penny toys were a hit

The mass production of toys and novelties from the last quarter of the 19th century enabled all but the poorest Londoners to buy penny toys.

These were very popular around Christmas time. Traders would attract large crowds of Christmas shoppers – and cause disruption to the flow of traffic and people through the financial area of the City.

In our collection, you can find mechanical toy models representing new technology and innovations, like a sewing machine and an electric omnibus. And while they were manufactured in Germany, many were designed specifically for the British market. There’s a model of the Royal Navy’s HMS Indomitable, for example.

“Casual street sellers were some of London’s poorest citizens”

The life of London’s street sellers

Casual street sellers were some of London’s poorest citizens. At Christmas their ranks were swelled by children, the disabled and the elderly desperate to benefit from the growing commercialisation of Christmas. London’s poor were notoriously resourceful and wasted no opportunity to “turn a penny on the streets”.

Watercolour of street sellers in Drury Lane in the West End.

Within a few years of Ernest starting his collection, the great social investigator Charles Booth issued his first survey of London’s poor that identified street sellers as being among the poorest of the capital’s workers. Classed alongside “loafers, criminals and semi-criminals”, the occasional street sellers lived the “life of savages, with vicissitudes of extreme hardship and their only luxury is drink”. Experiencing “an appalling amount of poverty and discomfort”, they were often found to be living in licensed common lodging houses and casual wards.

Not only is Ernest’s collection a great documentary of street life in the late Victorian and Edwardian period, it also represents the desperation of those who had no welfare state to depend on. His wonderful collection remains a legacy of his concern for the street sellers he supported for 25 years.