What were London’s pleasure gardens?

Imagine a place where wealth and high culture collided with danger, drunkenness and debauchery. For an evening’s entertainment, there was nothing quite like London’s pleasure gardens.

1700s–1800s

Glitz and glamour – with a seedy underbelly

Pleasure gardens were the place to be in the 1700s and 1800s. If you could afford the entry fee, you could mingle under the stars with the city’s fashionable clientele for a night of music, dancing, drinking and eating. They were a highlight of London’s summer nightlife for over 100 years.

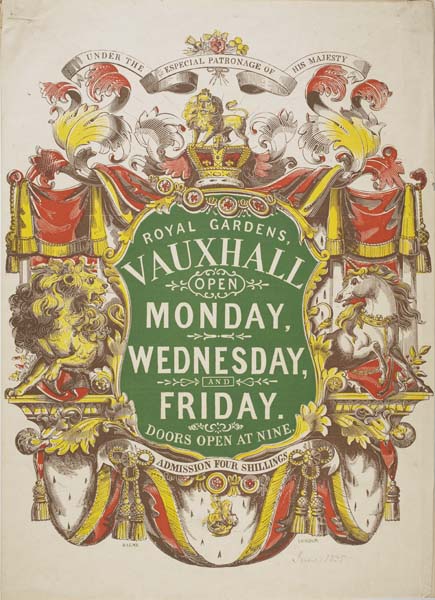

London had a number of different pleasure gardens, each open in the evenings during the summer months. Vauxhall, near Lambeth, and Ranelagh, in Chelsea, were the largest and most famous.

Pleasure gardens began as the height of fashion and culture. But into the 1800s, many had earned shady reputations and they went irreversibly ‘downmarket’. By the late 19th century, they’d all disappeared.

How did pleasure gardens come about?

Thanks to rising incomes and the growth of an urban middle class, Londoners sought out new entertainment and ways of socialising in the 1700s. Pleasure gardens were the answer for those looking to splash some cash on the city’s most exciting cultural offerings.

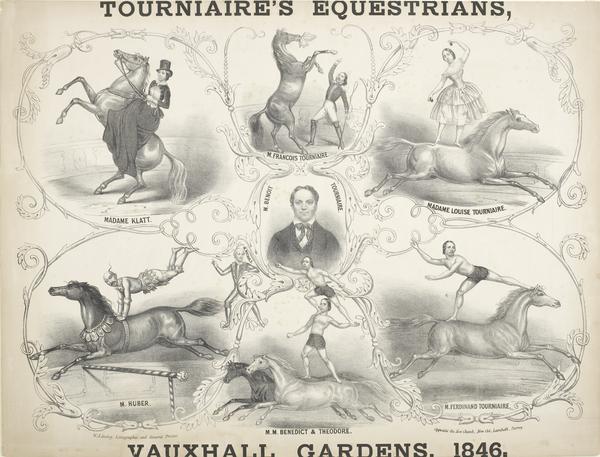

The first and most famous pleasure garden was in Vauxhall. It opened as New Spring Gardens in 1660, was relaunched by entrepreneur Jonathan Tyers in 1729, and renamed Vauxhall Gardens in 1785. Vauxhall’s more exclusive rival, Ranelagh Gardens, opened in Chelsea in 1742. Smaller gardens also opened around the same time, such as Marylebone Gardens in 1738.

How much did entry cost?

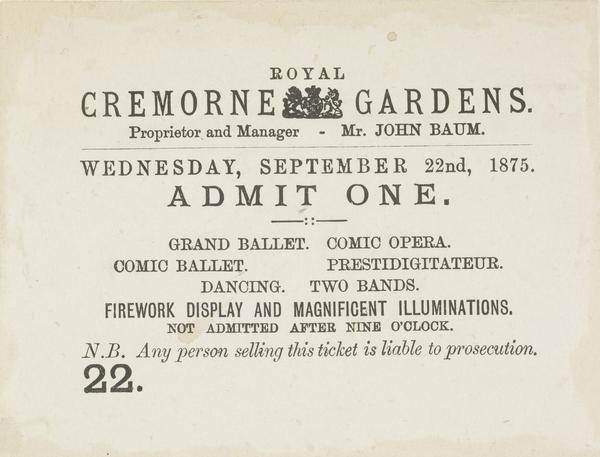

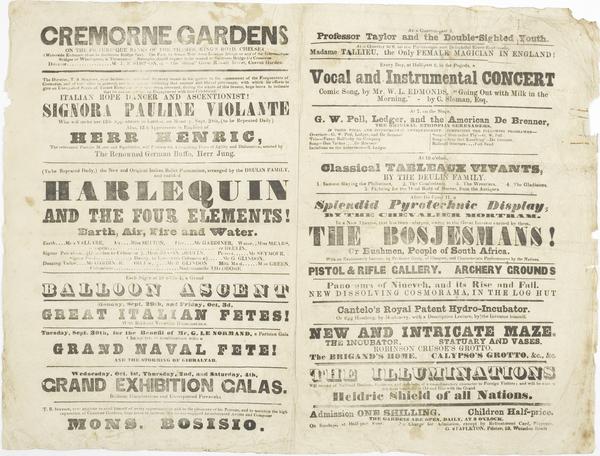

Pleasure gardens weren’t accessible to everyone. Both Vauxhall and Cremorne Gardens, which opened in the 1830s, cost a shilling. Most Londoners couldn’t afford this. In 1834, for example, a labourer earned around 10 shillings a week. Ranelagh’s entry fee was even more expensive: two shillings and six pence.

“Fine pavilions, shady groves, and most delightful walks, illuminated by above one thousand lamps”

England Gazetteer, 1751

What did they look like?

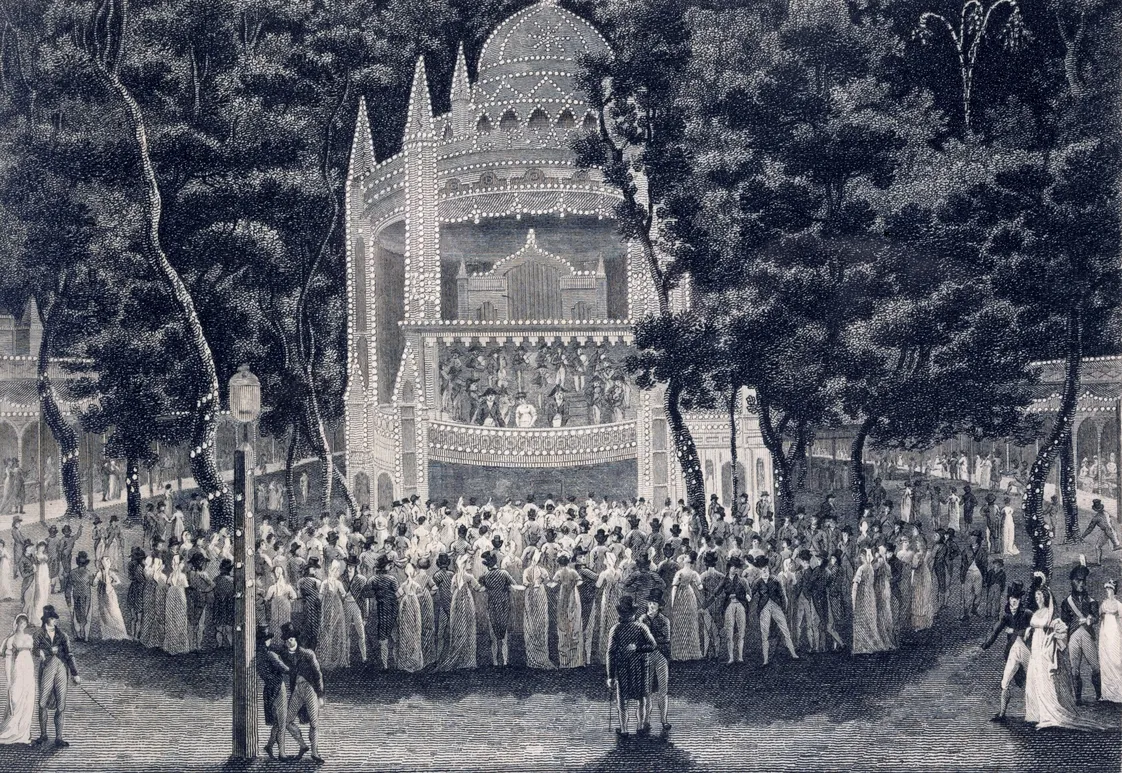

Pleasure gardens were landscaped outdoor venues that featured, as described by the England Gazetteer in 1751, “fine pavilions, shady groves, and most delightful walks, illuminated by above one thousand lamps”.

They were places to see the latest in art. Vauxhall displayed paintings by William Hogarth and Francis Hayman, effectively becoming Britain's first public art gallery. And their architecture was inspired by countries across the world, like Chinese-influenced pavilions and Italian piazzas

They also had dedicated buildings for entertainment. Ranelagh’s main attraction was its chandelier-lit rotunda, featuring booths for eating and drinking and an orchestra stand. Not to be outdone by its rival, Vauxhall subsequently built its Music Room in 1748.

What did people do at pleasure gardens?

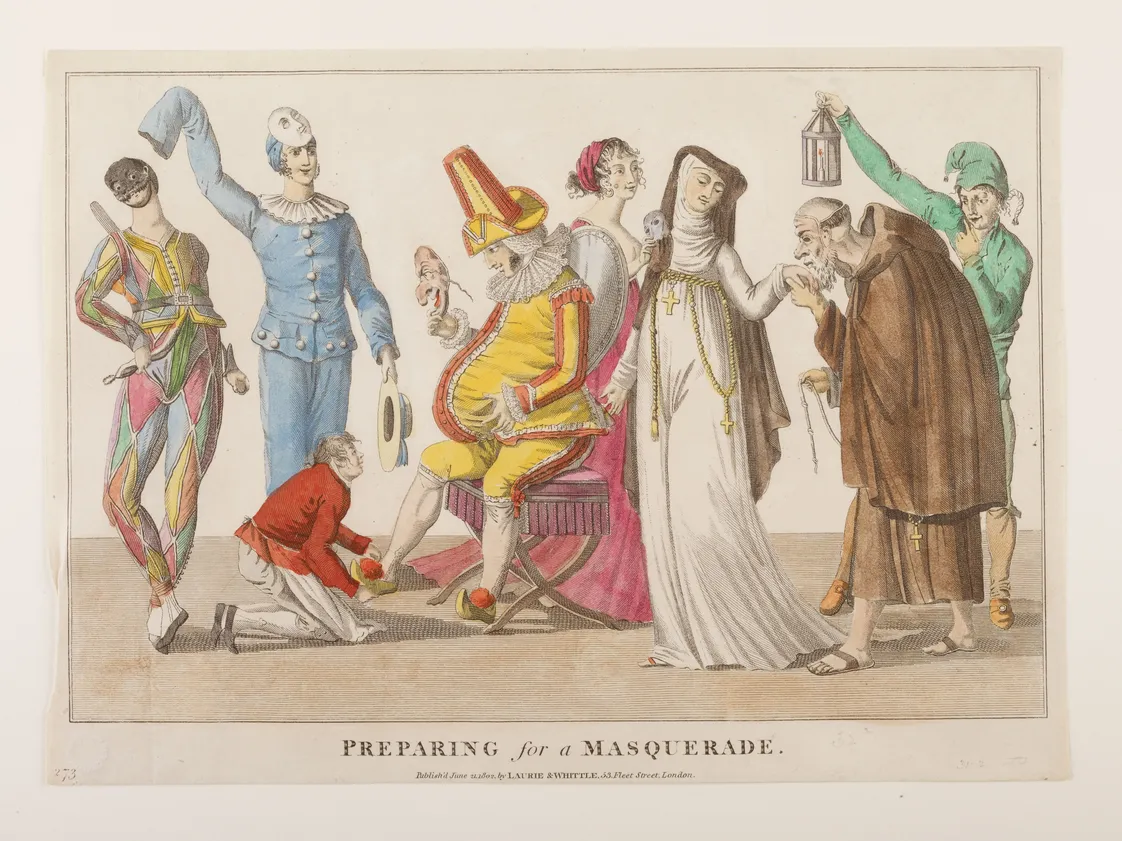

Londoners drank, danced and dined at pleasure gardens. They’d show off their finest clothes, don costumes for masquerade balls and enjoy music from contemporary composers and performers. An eight-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart even performed at Ranelagh in 1764.

“Dangerous, dubious places full of drunkenness, scandal and sex”

They were places where people of different genders could meet freely – and in the earlier years even mingle with celebrities, royals and the wealthy. But gardens like Vauxhall and Cremorne developed reputations as dangerous, dubious places full of drunkenness, scandal and sex.

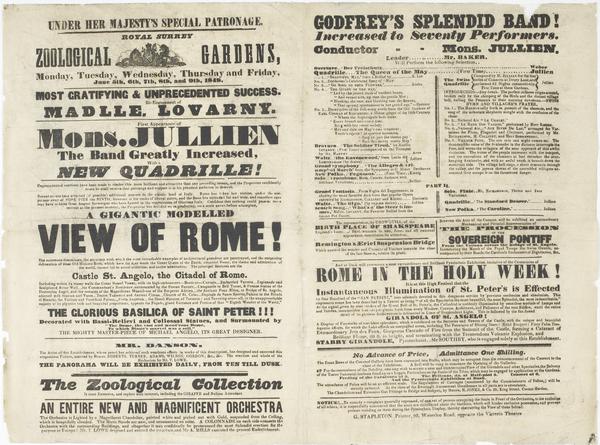

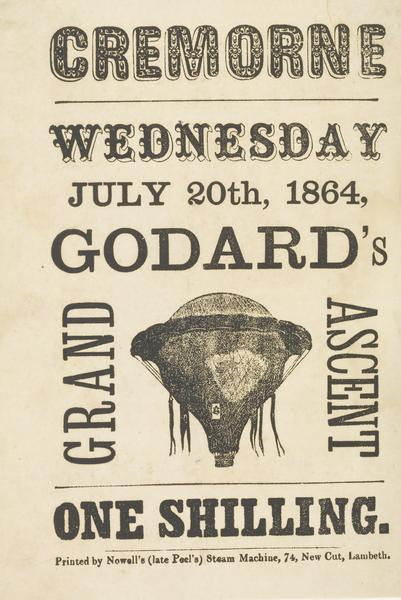

By the 1800s, the wealthy, fashionable crowds had drifted away. Gardens competed to keep the crowds coming by hosting new, ambitious entertainment. Hot air balloon rides, acrobatic displays, popular ballads and fireworks were the order of the day.

Crowds gather at Vauxhall Gardens to watch a balloon ascent.

The Surrey Zoological Gardens in Walworth, which opened in 1831, even displayed animals like a rhinoceros, orangutan and giraffes as part of its entertainment package.

Why did the pleasure gardens close down?

The development of music halls, casinos, public art galleries and public houses (‘pubs’) in the 19th century drew crowds, and their cash, away from the pleasure gardens. The growth of the railways also gave Londoners access to entertainment further afield.

Ranelagh closed in 1803. The owners of Vauxhall were declared bankrupt in 1840, and the gardens eventually shut its doors in 1859. Other 19th-century pleasure resorts like Surrey and Cremorne were also short-lived, closing in 1856 and 1877 respectively. It was an era never to be repeated.