What was the Great Exhibition of 1851?

Over one long summer, millions of people travelled to London to visit the first ever international exhibition showcasing industry, raw materials, art and design from Britain and abroad.

Hyde Park, City of Westminster

1 May – 11 October 1851

Curiosities, creations and a celebration of empire

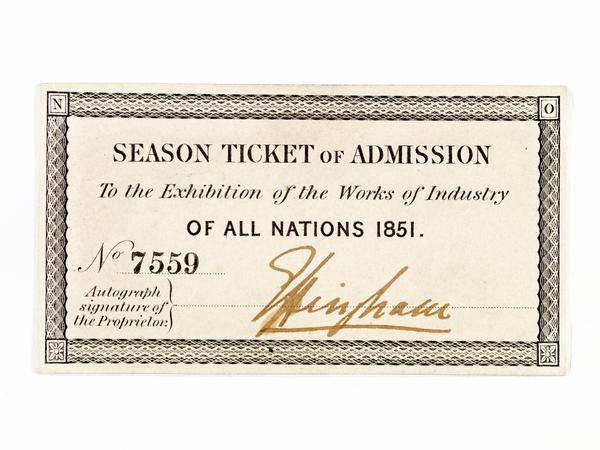

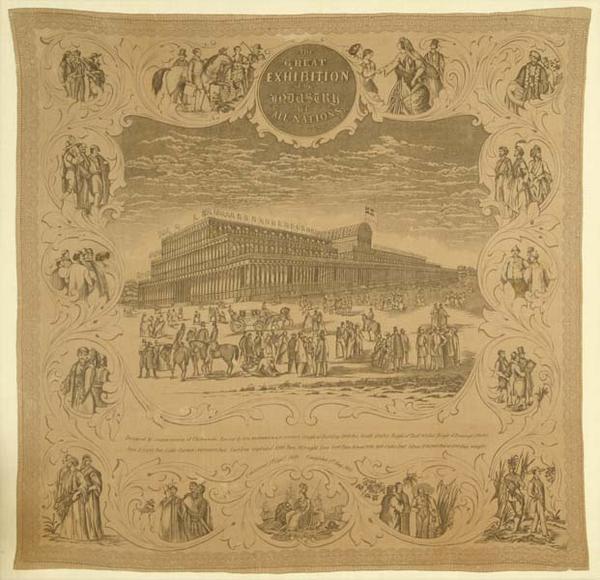

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, to use its full title, was one of the most popular public attractions in 19th-century London.

The creation of Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert and civil servant Henry Cole, the Great Exhibition aimed to celebrate modern design and promote Britain as an industrial and imperial power.

It was quite the spectacle: over 100,000 products from all four corners of the world were housed in a giant glass building. Open to everyone from all classes and nationalities, it aimed to push a positive view of the British empire to the largest possible audience.

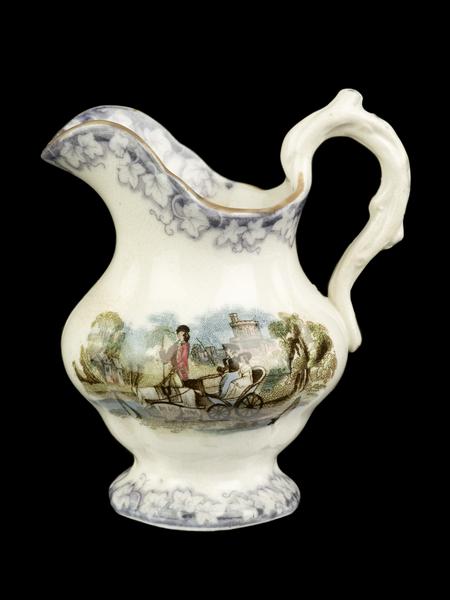

We have many objects related to the Exhibition in our collection, including prints and souvenirs commemorating the event.

Where was the Great Exhibition held?

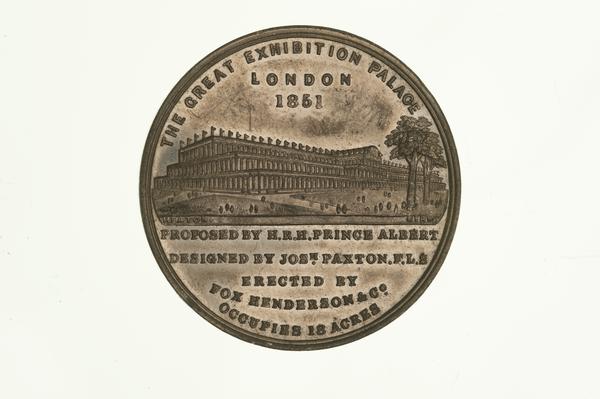

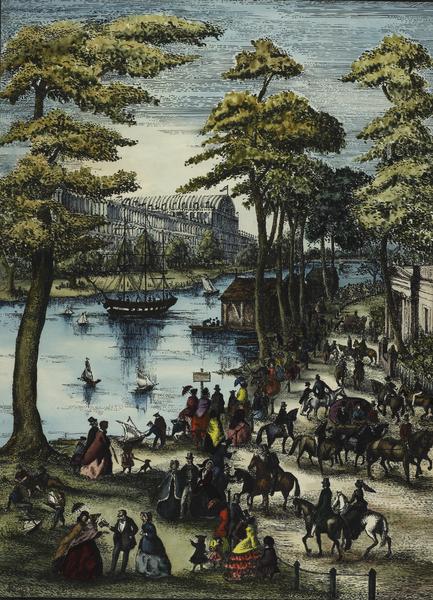

The exhibition was housed in a purpose-built glass and iron building in Hyde Park, Westminster. It was quite the engineering achievement – glass wasn’t really used as a building material at the time.

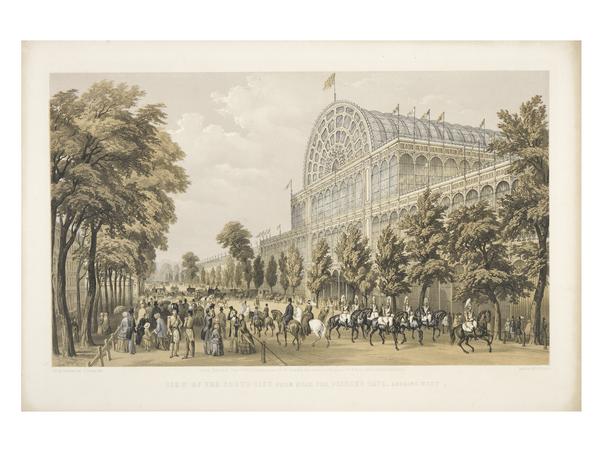

Crowds gather in front of the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park.

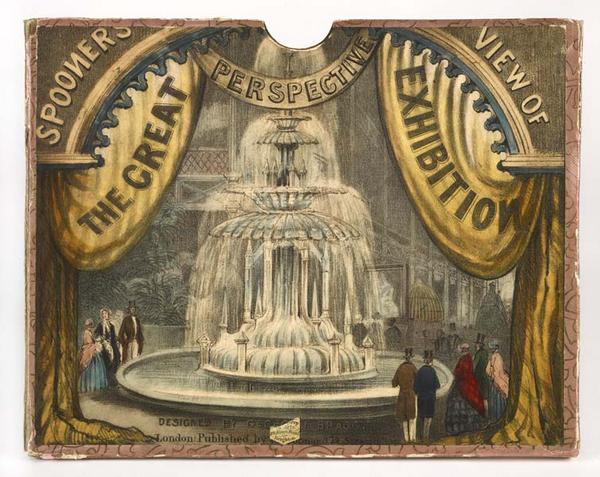

Designed by architect and gardener Joseph Paxton, the building was constructed in just nine months by over 2,000 workers. It was huge, tall enough to house full-grown elm trees, a pipe organ and an 8 metre glass fountain. The satirical magazine Punch dubbed it the ‘Crystal Palace’.

What was on display?

Visitors set their sights on the many marvels of the 19th century. A stroll along one of the gallery wings could take you past a medley of displays of fabrics, furniture, locomotives, hydraulic presses and musical instruments.

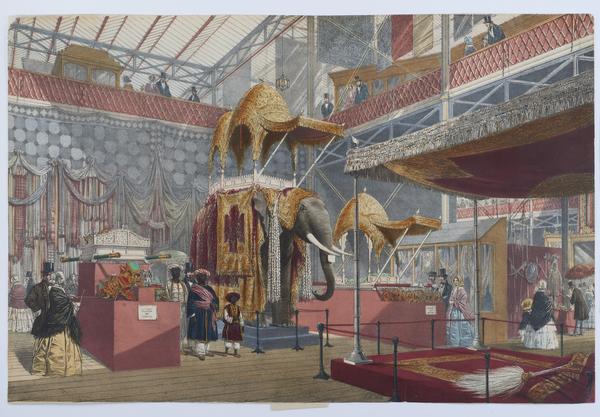

Exhibits were designed to contrast Britain’s technological and industrial superiority with that of the rest of the empire. The imperial displays presented a view of ‘exotic’ and ‘underdeveloped’ economies, implying a racial hierarchy to further justify imperialism. The Caribbean section, for example, showcased raw agricultural produce like sugarcane to represent Britain's exploitation of its expanding empire’s resources.

Illustration by artist John Nash of stalls showing produce from British colonies, such as sugar cane and bananas.

Some of the most popular exhibits included an iron piano frame and a stuffed elephant bearing a magnificent Indian howdah (seat). American sculptor Hiram Power’s lifelike marble nude titled Greek Slave was widely admired – and it became the site of abolitionist demonstrations.

There was also the Koh-i-Noor, the world’s largest known diamond. Queen Victoria had acquired the diamond in 1849 following British victory in the second Anglo-Sikh war. It was surrendered as part of the Treaty signed after the violent conquest and annexation by the British of the Punjab, northwestern India. The diamond still forms part of the Crown Jewels as a symbol of Britain's exploitative colonial past.

Was it a success?

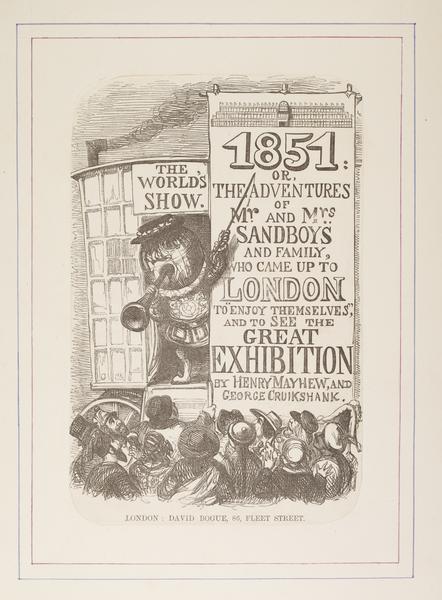

Six million people – equivalent to a third of the entire population of Britain at the time – visited the Great Exhibition. Among them were A-listers like authors Charles Dickens and Charlotte Bronte. It even inspired poems and books – including a comic novel by Henry Mayhew, whose satirical illustrations by George Cruikshank are in the collection.

But it wasn’t an exclusive event. ‘Shilling days’ were introduced a few weeks in, where entry was reduced from five shillings to one shilling, Monday to Thursday. Most people could now afford to go. And thanks to Britain’s newly constructed railway network, they could travel to the Great Exhibition from all over the country. Visitors took home souvenirs, like plates and fans, to remember the event.

The Great Exhibition was designed to present a very positive image of empire to the masses. By attracting millions of visitors, the event played a key role in spreading awareness of and support for the country’s imperial ambitions among the public.

“It will no more be asked at every breakfast table in the metropolis, ‘Who will go to the Exhibition’?”

The Times, 1851

It became a symbol of national pride – with a focus on London. On its closing, The Times wrote: “The country will no longer pour into the town, Piccadilly will cease to be a thoroughfare of nations, and it will no more be asked at every breakfast table in the metropolis, ‘Who will go to the Exhibition,’ and when, and how, and with whom?”

What was the legacy of the Great Exhibition?

The Exhibition was also a commercial success. It made a £186,000 profit. That’s over £20 million in today’s money. This was spent on transforming an area of South Kensington into a new cultural quarter, sometimes referred to as ‘Albertopolis’ after Prince Albert.

The profits were used to found the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Science Museum and the Natural History Museum. They also established an educational trust to provide grants and scholarships for industrial research.

What happened to the Crystal Palace?

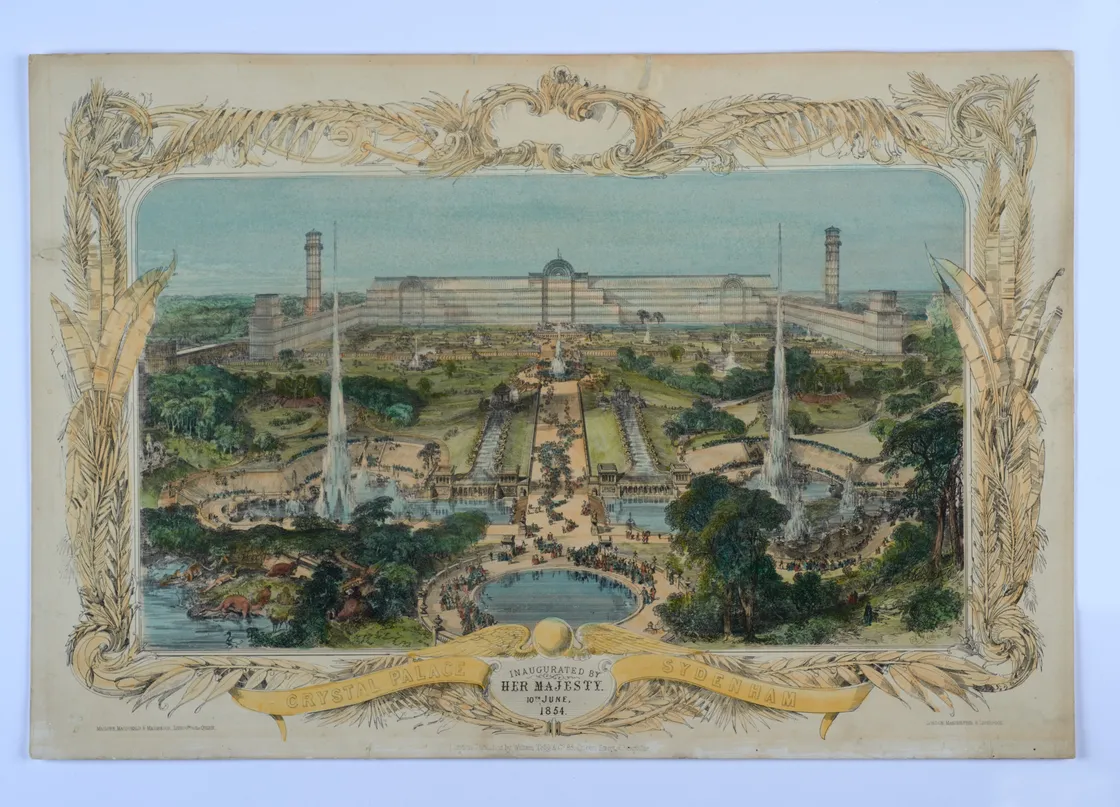

Shortly after the exhibition, the entire structure was removed from Hyde Park and reassembled in Sydenham Hill, then a part of the Kent countryside. This was no cheap task: the relocation cost over £1 million.

The Crystal Palace in Sydenham.

Despite being the popular centrepiece of the new Crystal Palace Park, the palace was plagued with financial problems and was declared bankrupt in 1911. It was eventually destroyed by fire in 1936.