West India Docks

Opened in 1802, West India Docks was built to handle goods from Caribbean slave plantations. As part of London’s busy port, it hummed with trade for 180 years.

Isle of Dogs, east London

1802–1980

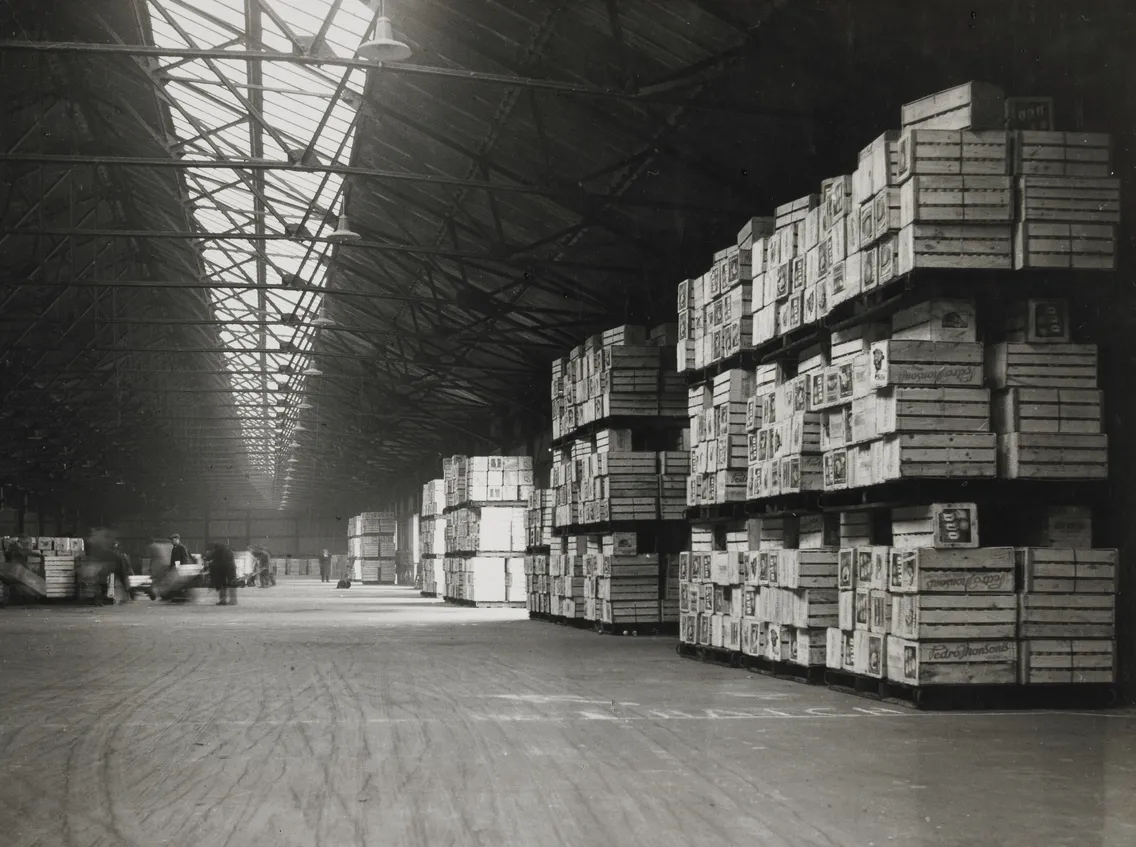

Dock workers unload potatoes from a ship on West India Docks' North Quay in 1948.

Slavery's lasting legacy

In the 18th and 19th centuries, wealth poured into London from the British trade in enslaved Africans and the sugar produced on Caribbean slave plantations.

London became a global centre of finance and trade – but it was built on the trafficking and enslavement of hundreds of thousands of African people.

That history is most obvious at West India Docks in east London. The dock complex was the largest in the world – created by and for merchants trading in the Caribbean.

West India Docks thrived beyond the banning of slavery in 1833. It was busiest in the 1960s. But shipping moved out of London in the 1980s, and the docks were transformed into Canary Wharf – a towering financial district for workers in suits and ties.

Today, our London Museum Docklands lives in one of the last surviving 19th-century warehouses, telling the stories of the city’s port and the brutal trade that made it rich.

Why were the docks built?

Before 1800, ships arriving to drop their goods in London crowded into the stretch of river between London Bridge and Wapping. Ships’ cargoes often rotted before they could be unloaded.

To avoid the lengthy delays, new docks were proposed by merchants trading goods from their plantations in the West Indies, a part of the Caribbean.

The site chosen was the Isle of Dogs, where there was a big bend in the Thames. An act of government approved the project, and gave the traders a monopoly – preventing anyone else’s ships from stopping there for 21 years.

West India Docks gave London its first enclosed dock, but soaring trade with other parts of the British empire was soon followed by more. Between 1800 and 1806, London Dock and East India Docks were also built on the Thames’ north bank.

What did the docks look like?

Docks are man-made lakes which allow ships to unload their goods away from the river.

The West India Docks were enormous – almost a kilometre long, with moorings for 500 vessels. It was a vast, imposing project unlike anything seen before. In 1802, an observer commented: “Emperors and states have constructed harbours, and erected towns; but the history of the world may be ransacked in vain to exhibit anything of the kind.”

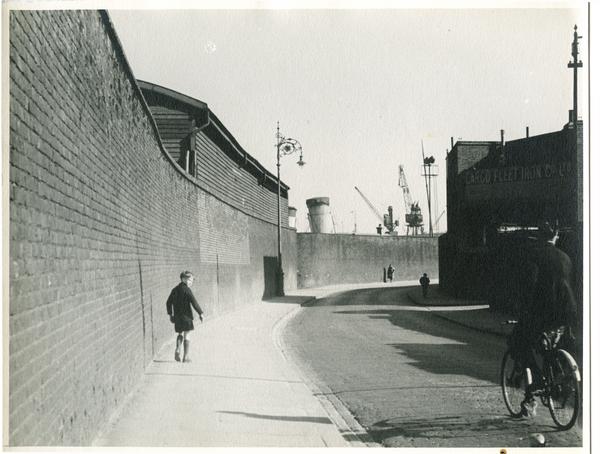

The docks were lined by enormous warehouses to keep the goods safe from theft. It was built like a fortress, with high spiked walls, a moat and its own police force.

This plan from our collection shows the layout of the West India Docks, although not all of the warehouses shown here were built.

The northern basin, where our museum is, was for unloading goods. The southern basin was for loading. Ships entered through the Blackwall Basin and exited through the Limehouse Basin. A separate canal giving ships a short-cut through the Isle of Dogs later became part of the docks too.

“the trade in sugar and the enslaved Africans needed to produce it made some people incredibly rich”

Number One Warehouse

This is one of only two surviving West India warehouses. It’s now home to London Museum Docklands.

The enormous brick and timber warehouse was built to hold sugar and rum. It had three floors, plus a basement. In 1827, another floor was added for lighter goods like coffee.

Dock workers moved goods from ships into the warehouses for storage, hoisting them up to the upper floors and passing them through open doorways facing the dock.

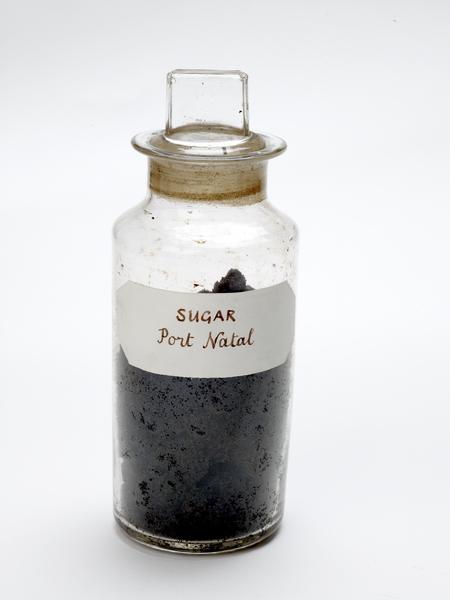

Sugar was the main money-maker

By the 1790s, a quarter of Britain’s income came from imports from the West Indies. Most of it landed in London. Sugar, rum, coffee and timber were the main imports.

But sugar was the biggest trade of all. Between 1700 and 1800, the popularity of coffee drove demand for sugar to sweeten the bitter drink. In 1781, almost 55 million kg of sugar was imported to Britain.

Number One Warehouse was built to hold 80,000 giant barrels of sugar, and 20,000 smaller barrels of rum, an alcoholic spirit also made from sugar.

In the Caribbean, sugar cane was grown on plantations which used enslaved Africans for labour. The trade in sugar and the enslaved Africans needed to produce it made some people incredibly rich. London was the fourth biggest slave-trading port in the world, and West India Docks was also used by ships heading to Africa to buy enslaved Africans.

Sugar continued to be imported into London long after slavery was made illegal in 1833. Photos in our collection show sacks piled high in the warehouses in the 1930s.

Dock workers hated carrying these sacks. The moist, gritty sugar would crack and cut their hands, necks and heads so much that a street between two warehouses became known as Blood Alley.

The 20th-century docks

By 1900, the West India Docks had become part of a global trade network tied together by the British empire. Goods arrived from other parts of the world, not just the Caribbean.

In 1936, a new warehouse was built to handle fruits and vegetables from the Canary Islands, off the coast of Africa. This was the original Canary Wharf.

Rebounding from the war

London relied on imports to feed the city and keep its economy running. That made the docks the main target of the German bombing campaign during the Second World War (1939–1945). West India Docks was badly damaged, with only two warehouses surviving.

After the war, a massive rebuilding project got the docks back to business within 10 years. By the 1960s, they were busier than ever. The docks reflected the new wealth of “Swinging London”.

Redeveloping West India Docks

From the 1960s, all of London’s docks began to lose business. Ships got bigger – too big for many docks – and adopted shipping containers, which London’s docks couldn’t process. Ships landed further east at Tilbury in Essex instead.

West India Docks closed in 1980 and soon became derelict. In 1981 Margaret Thatcher’s government began to redevelop London’s docklands. Much of West India Docks became the Canary Wharf financial centre, where tall glass tower blocks housed banks and law firms.

The Robert Milligan statue

London Museum Docklands opened in Number One Warehouse in 2003.

From 1997 until 2020, a statue of Robert Milligan stood outside the building. Milligan traded enslaved Africans and owned sugar plantations in Jamaica that used enslaved people as workers. He was one of the founders of the West India Docks.

The West India Docks Company erected the statue in his honour after his death in 1809. It was unveiled in 1813 near the dock offices, before moving to the main gate in 1875. The statue was placed into storage in 1943, but was re-erected in 1997. This time, it was placed on a different spot, opposite Number One Warehouse.

In the wake of the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, when a statue of the enslaver Edward Colston was torn down in Bristol, the Milligan statue was removed by Tower Hamlets Council and the Canal and River Trust.

The Milligan statue is now in our museum’s collection, where it can help us highlight the lingering legacy of slavery in Britain, as well as the modern reckoning with that past.

A memorial to the victims of slavery will stand outside London Museum Docklands in the statue's place.