Wenceslaus Hollar’s etchings of fashion & fire

Wenceslaus Hollar was a 17th-century artist best known for drawing detailed views of London – but his series on women’s fashion is equally fascinating.

1607–1677

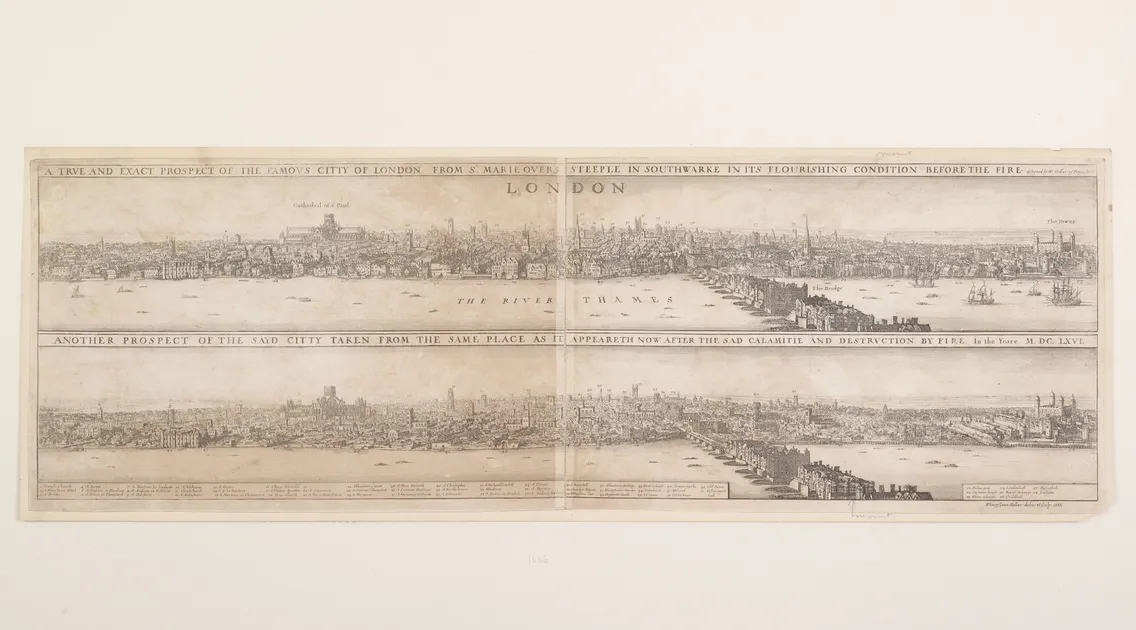

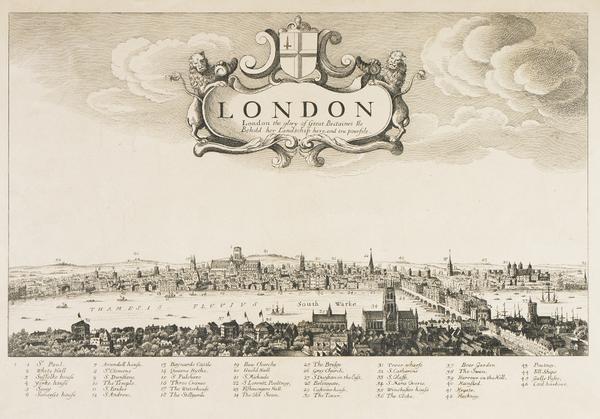

What you'd see looking at the City across the Thames in 1647, before the Great Fire.

Drawing London’s ever-changing looks

London’s skyline and London fashion never stand still for long.

Lucky for us, Wenceslaus Hollar chose both as the subject of his drawings. Hollar captured the city before the 1666 Great Fire of London and after it, showing how it transformed in just a few, destructive days.

And he documented the way women of different classes dressed in the 1630s. Their masks, ruffs and fur muffs were the peak of style then – could it be time for a revival?

“it was considered good manners to remove the mask when meeting friends”

Masks covering the top half of the face were fashionable in the 17th century.

A touring artist

Hollar was born into a well-known Protestant family in Prague, now the capital of the Czech Republic. His father wanted him to follow a bureaucratic or legal career. Instead Hollar became an artist, although he seems to have had no formal training.

Hollar travelled Europe, before being brought to London in 1636 by Thomas Howard, earl of Arundel.

Howard hired Hollar to make etchings, a type of image made by printing with a metal plate. After arriving, Hollar mainly set about making original work and searching for other patrons.

Women’s fashion in the 1630s

One of his first major projects was a set of etchings of women’s outfits in the late 1630s. Prints of these are in our collection. Titles from this time were rarely snappy – he called it: The severall habits of English women from the nobilitie to the country woman.

Plates 1–16 show the elaborate outfits worn by ladies of the highest rank at court. Another eight show outfits likely to have been worn by a smart woman in town. In the final image, a woman dressed for the country is shown carrying a basket of vegetables.

Among the standout fashion items are ruffs, luxurious fur muffs, wide-brimmed hats and a mask covering the eyes (it was considered good manners to remove the mask when meeting friends).

Hollar also drew the wife of the Mayor of London, who wears a lace-trimmed ruff and kerchief, and holds a feather fan.

The wife of the Mayor of London.

But just like today, style varied across Europe – another series by Hollar shows the outfits of European women in cities like Basel, Naples and Dieppe. You can spot some obvious differences across the continent, especially in the many, many types of headwear.

Women's outfits in Strasbourg in the 17th century. It's not certain that this is Hollar's work.

How London’s skyline changed after the Great Fire

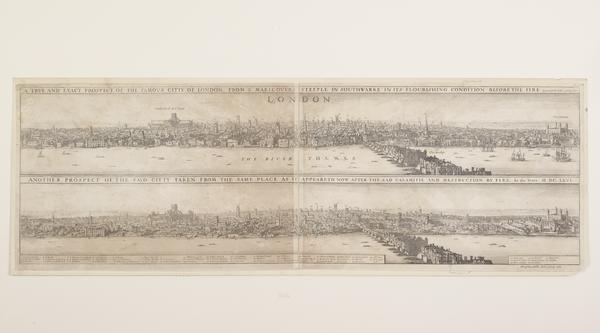

Between 1636 and 1644, Hollar drew various buildings and views of London which served as source material for later works. His famous Long View of London from Bankside was printed after he had left for Antwerp in Belgium in 1647.

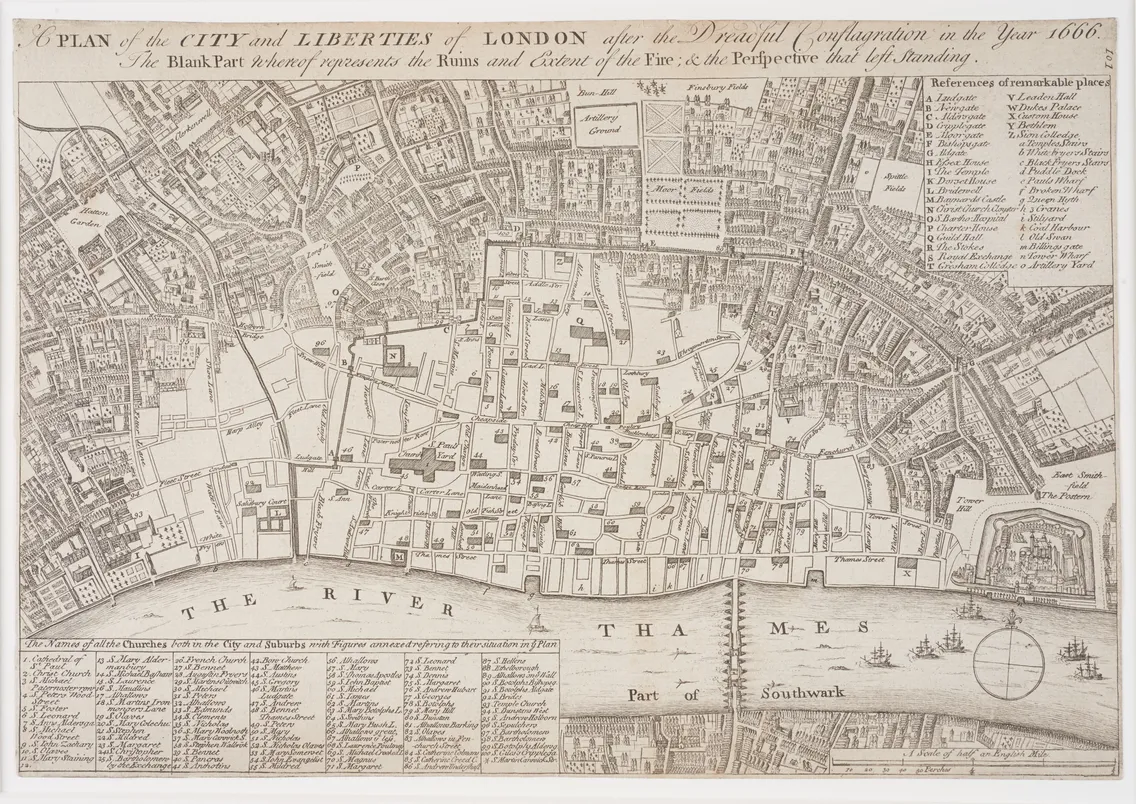

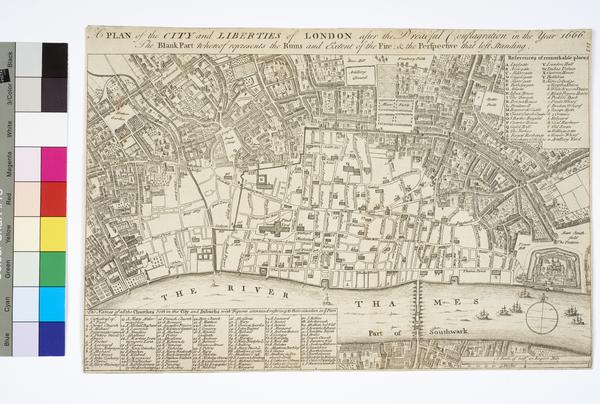

Hollar returned to London in 1651 or 1652, where he worked for the publisher John Ogilby and the antique collector Sir William Dugdale. He planned to make a large-scale map of London – but that plan was scuppered by the Great Fire of 1666.

The fire instead gave him the opportunity to produce new views of the city to reflect the damage.

In one etching produced in 1666, Hollar places a view of the city before the fire over the same view after the fire. The contrast is dramatic. The spires of churches and the brick chimney stacks of houses are some of the only structures still standing.

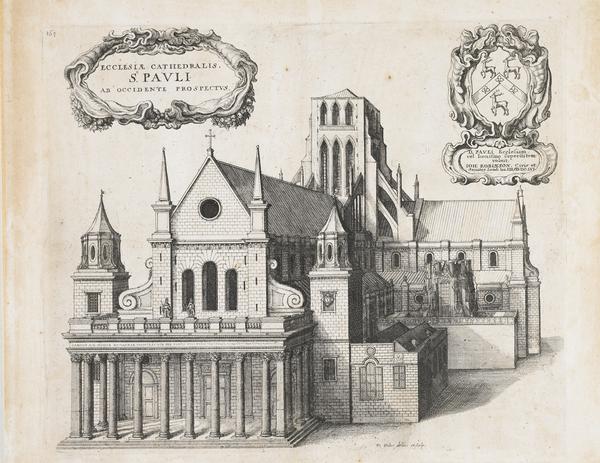

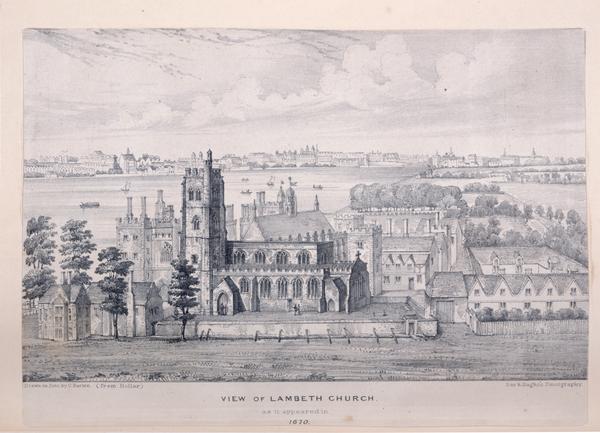

Other drawings of buildings by Hollar in our collection show St Paul’s Cathedral before the fire, a view of Westminster from across the River Thames, Lambeth Palace and the Palace of Whitehall.

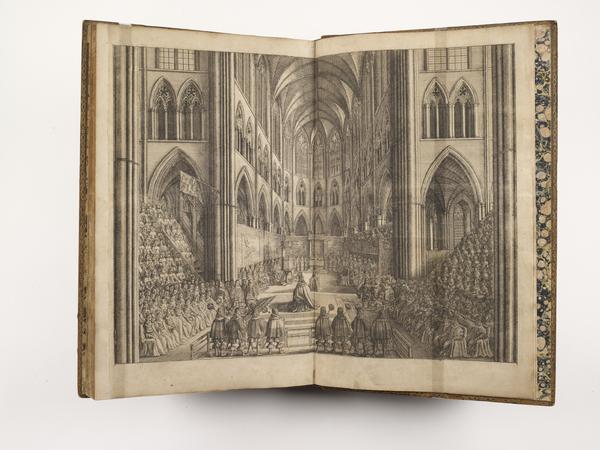

He drew the coronation of King Charles II in Westminster Abbey too, when the monarchy was restored after the English Civil Wars, as well as portraits of Charles II and Charles I.