The Walbrook Skulls: A Roman murder mystery

In 1988, the skulls of 39 Roman Londoners were found in the City of London, in what was once the Walbrook valley. Many had suffered violence – causing speculation they might be gladiators.

Walbrook, City of London

70–200 CE

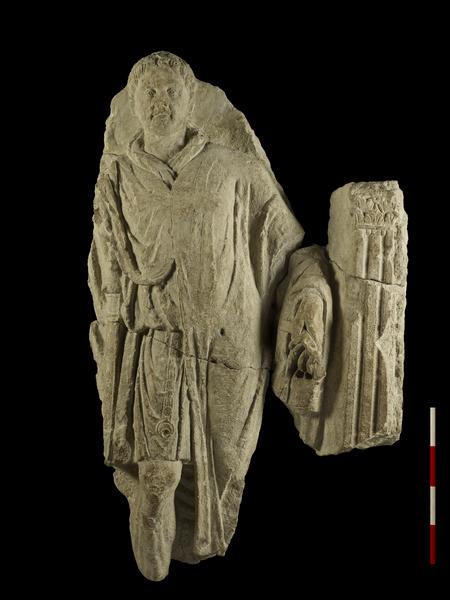

Trajan's Column in Rome, built 106–113 CE, showing Roman soldiers with the severed heads of their enemies.

This page contains content some people may consider sensitive, or find offensive or disturbing. Understand more about how we manage sensitive content.

Fallen gladiators? Executed criminals? War trophies?

Who did these skulls belong to? And why had they been decapitated? That remains a mystery.

But careful analysis of their bones by London Museum's Centre for Human Bioarchaeology gives us some fascinating clues.

Most were young men. Many had blunt-force injuries to their skull. And at some time between 70 and 200 CE, they’d all been left in ditches or open pits.

Two nearby sites – a military fort and amphitheatre – provide three possible theories.

These people may have been gladiators. They may have been executed as criminals. Or they may have died in northern wars, their skulls kept as trophies by Roman soldiers.

The Roman amphitheatre

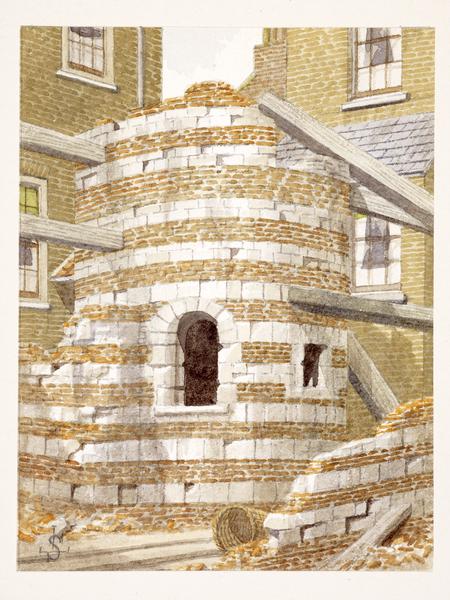

In 1985, developers rebuilding the Guildhall Art Gallery in the City of London discovered a Roman amphitheatre.

Around 100 metres long and 85 metres wide, the amphitheatre was used for religious activities, animal fights, public executions and on rare occasions, gladiator fights.

Today, you can see its outline in front of the Guildhall, picked out with a ring of dark stone.

The dark stones outside the Guildhall show the curve of the amphitheatre's outer wall.

Finding the Walbrook skulls

Three years later, archaeologists working just a few hundred metres away unearthed 40 human skeletons – or, more precisely, parts of skeletons.

There were 39 skulls and one thigh bone, all from different individuals.

Despite Roman law and religion banning burials within the city, the remains were excavated from inside the Roman walls. The River Walbrook ran nearby.

Most were between 18 to 35 years old when they died

The shape of the bones and wear on the teeth were clues to the people’s sex and age.

We know that 36 were male. We can’t be sure about the other four, because the parts of their skulls which we use to estimate a person’s sex never made it into the pit. Most were between 18 to 35 years old when they died.

Where did they come from?

Stable isotope analysis of two of the males found that they were likely to have spent their childhoods in Britain.

We also carried out ancient DNA analysis on one of these males. This revealed that he had brown eyes and dark black hair. His maternal ancestry matched groups across Europe, North Africa, the Near East and the Caucasus.

What injuries did the skulls have?

Ante-mortem traumas are wounds from before someone died, giving the bone time to heal. They tell us about the person's life, and how often they had been injured before their death.

Many of these individuals had multiple head traumas, ranging from dental damage to skull fractures. It suggests they lived violent lives.

Peri-mortem traumas are wounds sustained at or shortly after death. Most of these 39 skulls had blunt-force traumas sustained at the time of death. Five had sharp-force weapon injuries, which could have been caused by a Roman soldier's sword or a gladiator’s weapon.

A skull with a healed fracture of the left cheekbone.

More clues

One skull showed signs of being gnawed by a dog, showing that soft tissue was still present when the heads were placed in their pits.

Another had the wing-case of a water-beetle lodged in its nasal cavity, suggesting it spent time lying in an open pit with pools of stagnant water.

The remains were put into pits and ditches between the 1st and 3rd centuries, about 70–200 CE – after Boudicca’s rebellion (60 CE).

This was not a period of violence or war in Roman London. The city was at its height. Large projects were underway, including the building of the fort and refurbishment of the amphitheatre.

Did the Walbrook skulls belong to gladiators?

Gladiators fought in amphitheatre games against other gladiators, animals or prisoners condemned to death.

The fighters could be ex-soldiers, enslaved people, criminals or free citizens. They lived and trained in special schools called ludi and fought across the empire, usually only two or three times a year.

Evidence suggests that the average age-at-death for gladiators was between 22 and 27 years old. This age range, and the many healed injuries of the Walbrook skulls, would fit with the theory of these men being gladiators who died in the amphitheatre.

Gladiator games were a popular spectator sport. Star fighters became Roman celebrities, featured on products like this clay lamp.

Despite this, gladiators were treated as social outsiders. They were excluded from formal Roman burial grounds. Perhaps this area of the Walbrook valley was used to dispose of people killed in the amphitheatre.

“Cutting off enemies’ heads and displaying them was a sign of bravery”

Were they executed criminals?

These men could have been criminals executed in the amphitheatre. Depending on their crime, the condemned could have been killed by hanging, decapitation, crucifixion, wild animals or burning.

Evidence from elsewhere in the Roman empire suggests that the majority of condemned were adult males, who had suffered extensive injuries before death.

Their remains – or parts of them – were often thrown into rivers or pits outside the walls of the settlements.

Had their remains been collected by headhunters?

These men might have suffered an even stranger fate.

Human remains found in wells, in military forts and outside temples suggest that people were killed and their body parts displayed for ritual reasons.

The Roman military were also strongly associated with headhunting. Cutting off enemies’ heads and displaying them was a show of bravery. Trophy heads were depicted on Roman soldiers' tombstones.

Many of the soldiers serving in Londinium would also have been stationed at frontiers in the north of Britain, battling Britons in Scotland and Northumberland.

These battles would have provided them with the chance for trophy headhunting. If they were later stationed at the fort in Londinium, they may have carried their grisly trophies south with them.