Vivienne Westwood & Malcolm McLaren: King’s Road royalty

From their ever-evolving boutique on 430 King’s Road, Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren shook up London fashion. They shaped the early punk look with designs incorporating Scottish tartan, leather and bondage gear.

Kensington & Chelsea

1971–1984

Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood.

Reinvention and provocation

King’s Road, Chelsea. Built as a private road for King Charles II to travel to Hampton Court Palace in the late 17th century, this west London thoroughfare became a countercultural hotspot in the post-war period.

Since Mary Quant set up her Bazaar boutique at number 138 in 1955, this very long street became known for its many experimental boutiques selling youth-focused fashion.

In the 1970s, attention was fixed on the shop at number 430. It was owned by Vivienne Westwood, previously a primary school teacher, and her boyfriend, the band manager Malcolm McLaren.

Not ones to stick to a style or follow trends, the couple rebranded their King’s Road boutique a total of five times over just ten years.

Let It Rock, 1971: Teddy Boy dreamland

In 1971, Westwood and McLaren started selling 1950s rock and roll records and memorabilia at the back of Paradise Garage, formerly a second-hand denim shop located at number 430.

Cotton shirt designed by Westwood and McLaren for Let it Rock.

The pair managed to eventually take over the whole shop. They renamed it Let It Rock and transformed it into an homage to the Teddy Boys, the rock and roll-loving, quiffed and velvet-collared subculture that emerged in London in the 50s.

Westwood gradually began to produce her own line of garments for the shop. They also sold t-shirts which they customised by cutting, stitching and printing subversive slogans and images onto them.

Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die, 1972: the bikers arrive

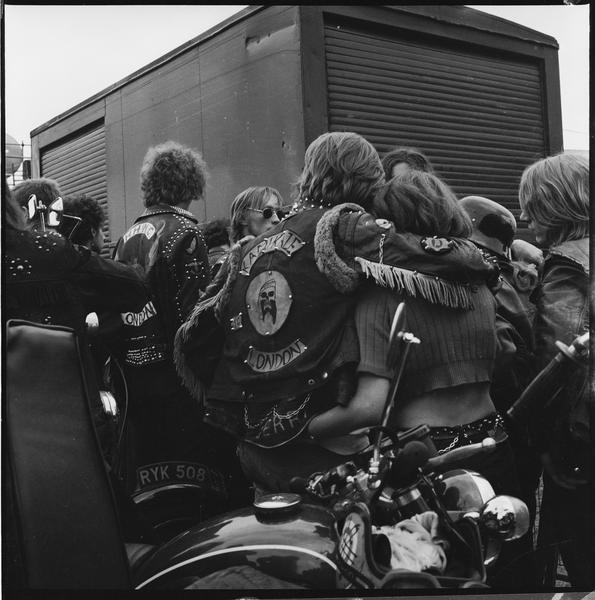

A skull and crossbones logo marked the next evolution at 430 King’s Road. In 1972, the shop leant further into biker fashion full of zips, studs and leather. It was renamed Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die.

Bikers at a music festival in Hyde Park, 1970.

The early 70s saw a continuation of the hippie fashions of the 60s. Barbara Hulanicki’s popular London boutique Biba was a destination for garments like bell-bottom trousers, mini-skirts and maxi dresses. Glam rock fashion – think jumpsuits, satin shirts, oversized collars and flared trousers – was also hitting the mainstream.

But none of this inspired Westwood and McLaren. Instead, they looked to the youth cultures of the past.

Sex, 1974: bondage and fetish fashion

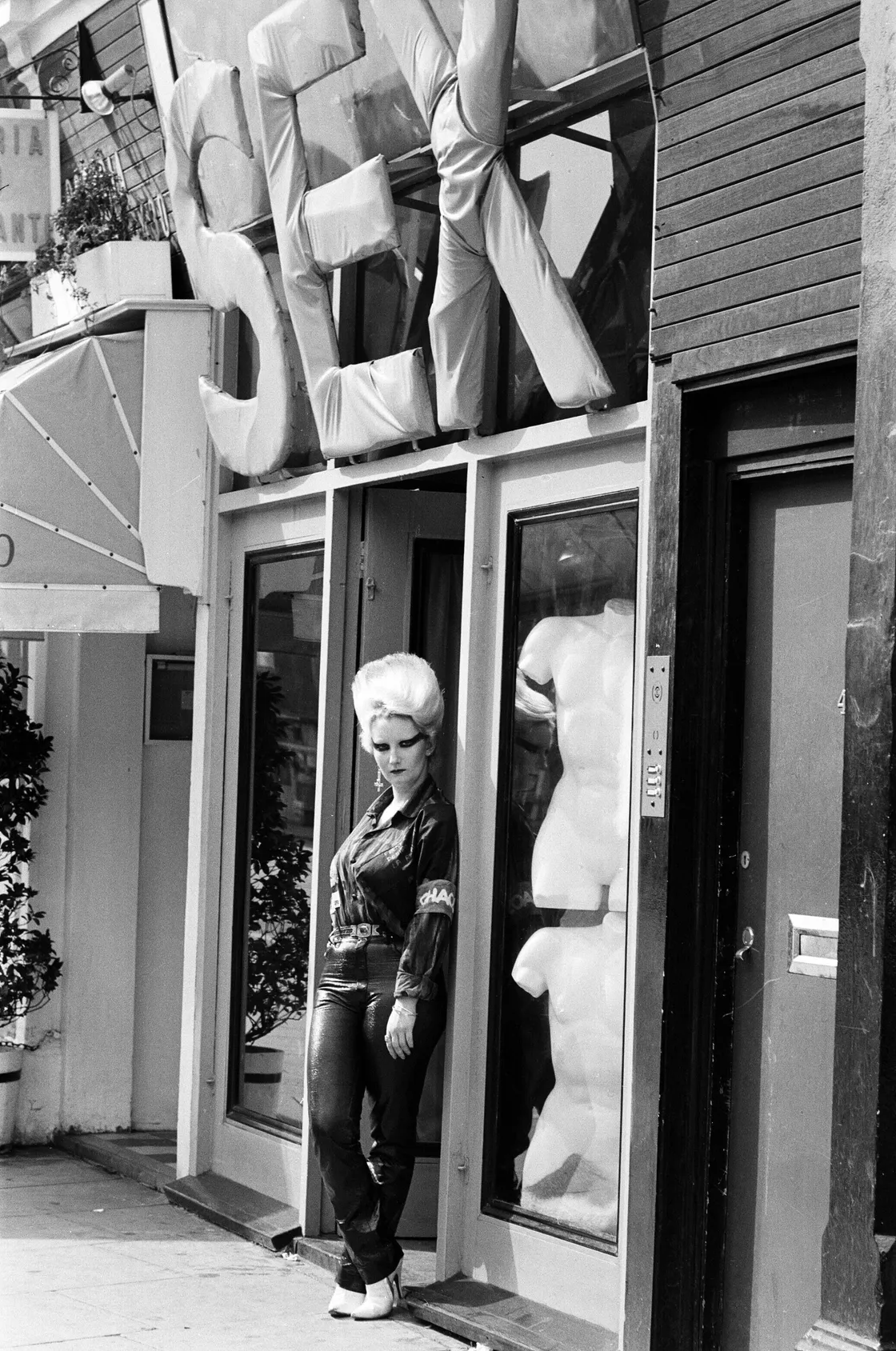

Things really exploded when, in 1974, huge pink padded plastic letters spelling ‘SEX’ were fixed onto the front of number 430. Sex stocked rubber, polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and fetish wear. Many of the items were customised by Westwood.

Pamela Rooke, aka, Jordan outside Sex, where she worked.

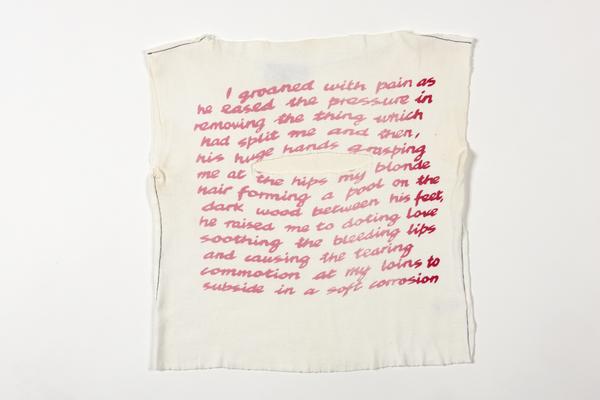

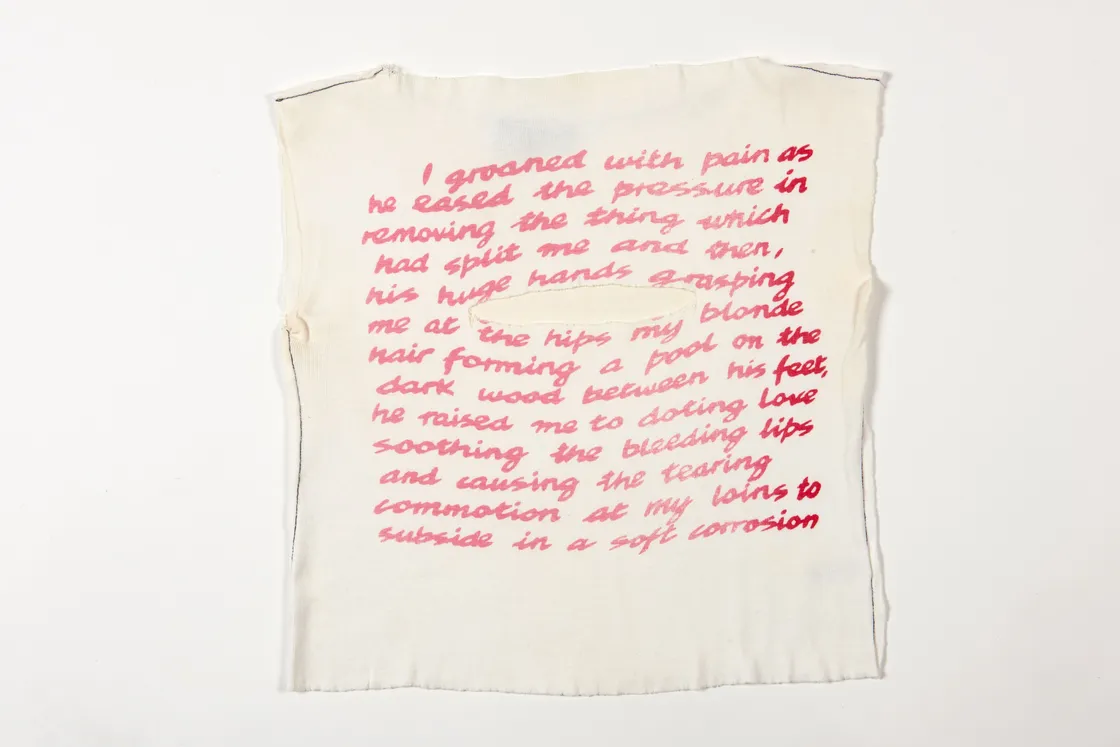

Westwood and McLaren also sold t-shirts featuring confrontational printed slogans and images. One tee of two cowboys, naked from the waist to their boots, led to Sex getting raided by police and the pair arrested. Their charge? An “indecent exhibition” at their shop on King’s Road.

“They would form my critique, help dress a new army of disaffected youth”

Malcolm McLaren, 2002

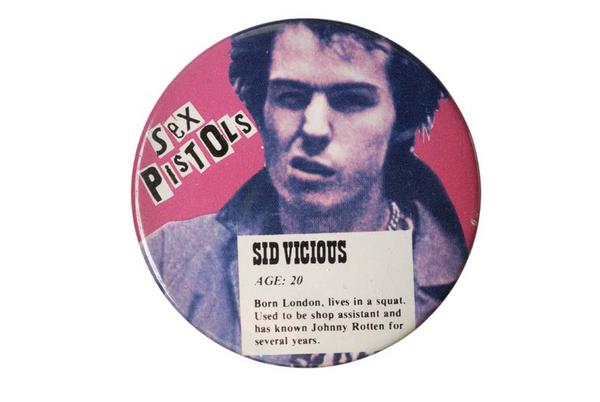

In 1975, McLaren started managing a new, young punk band to “spread the word” of the store. He named the band the Sex Pistols. “They would form my critique,” he told the Guardian in 2002, “help dress a new army of disaffected youth.” Original Sex Pistols bassist Glen Matlock even worked at the store as a sales assistant.

T-shirt designed by Westwood and McLaren for Sex, featuring text taken from Alexander Trocchi's book School for Wives.

Seditionaries, 1976: archetypal punk

Shock and awe continued in the shop’s fourth evolution of the decade: Seditionaries. Westwood brought together styles from number 430’s previous lives: strappy bondage-wear, leather, zips, chains and ripped, frayed fabrics. She also started working with tartans. Westwood described her designs as “romantic”, “primitive” and “tribal”.

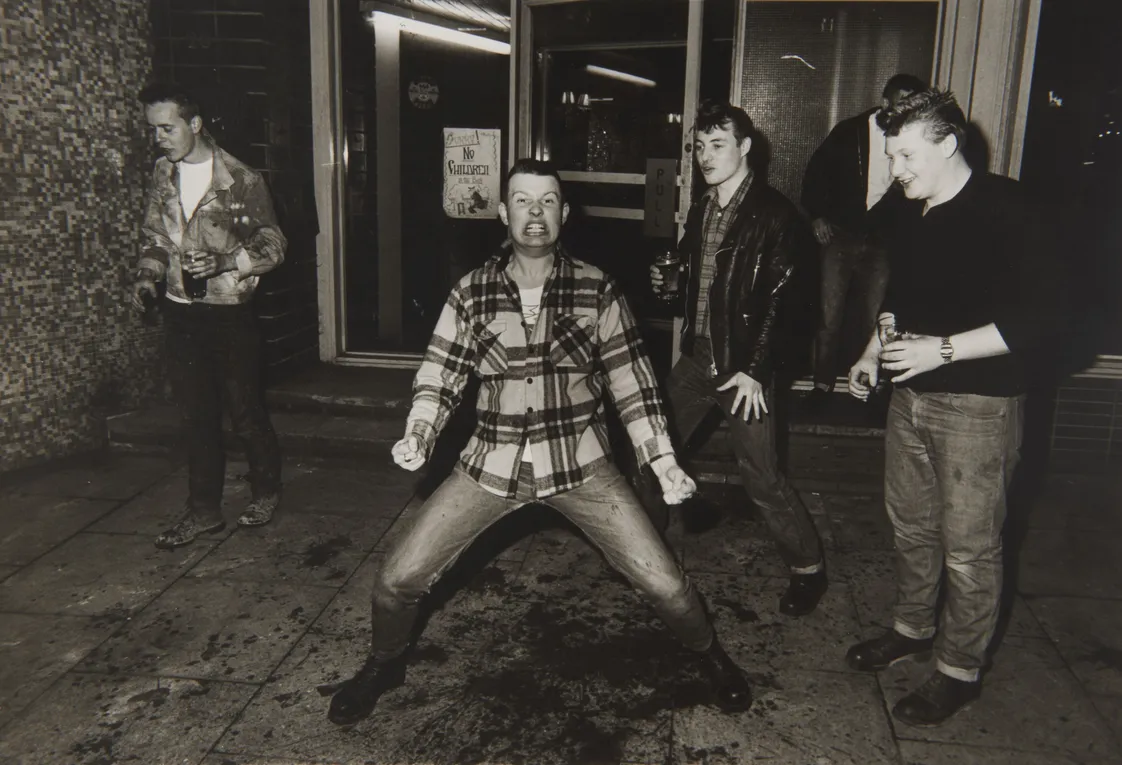

Both Sex and Seditionaries shaped the growing punk look. The Sex Pistols were cladded out in the shop’s gear. But many punks couldn’t afford it. Some resorted to walking out without paying and others made their own clothes.

Along with nearby boutiques Acme Attractions and Beaufort Market, the eastern end of King’s Road became a place of punk pilgrimage. Teds and punks clashed regularly out on the streets in the summer of 1977.

“I am not advocating violence, but I’m demanding freedom. I intend the clothes I design to cause a confrontation”

Vivienne Westwood, 1977

The shop sold more challenging t-shirts featuring nakedness, pornography or Queen Elizabeth II with a safety pin through her lips. These were pointed at the establishment not just with the aim to offend. They wanted social revolt. Westwood told a journalist in 1977: “I am not advocating violence, but I’m demanding freedom. I intend the clothes I design to cause a confrontation.”

Worlds End, 1980: Westwood and McLaren’s enduring legacy

Westwood and McLaren’s final boutique venture still stands at 430 King’s Road today. Worlds End’s wonky shop aesthetics haven’t really changed since the 80s. You’ll still encounter its giant, backwards-spinning 13-hour clock on the front.

Worlds End still stands at 430 King's Road.

In 1981, the couple launched their Pirate collection with their first mainstream fashion show at Olympia, an exhibition and events space in nearby Hammersmith. Inspired by the French revolution, rogue seafarers and African fabrics, the designs featured puffy sleeves, ruffles, breeches and a distinctive squiggle print. The collection heralded the arrival of the New Romantics style of the 1980s.

Soon after Pirates, Westwood and McLaren’s relationship ended. They stopped working together professionally in 1984. McLaren focused on making music. And Westwood’s career as a leading fashion designer began to fully take off.