The Victoria Cross found in the Thames

In 2015, a rare Victoria Cross medal – awarded for outstanding bravery – was discovered on the Thames foreshore. Who owned it, and what was it doing here?

River Thames

1854

A prestigious medal in the mud

Wading through the mud, mudlarks comb the shore of the River Thames to discover traces of London’s past. Anything they find must be reported to London Museum.

Our Finds Liaison Officer never knows what artefact or coin they’re going to be shown next. Some reflect the everyday life of Londoners. Others are more extraordinary.

The Victoria Cross (VC) is awarded to soldiers for extreme bravery in the presence of an enemy. Less than 1,500 have ever been awarded.

The medal from the Thames is one of the earliest VCs awarded, given to a soldier who fought during the Crimean War (1853–1856). We think it might have belonged to one of two men.

The discovery

The story started when Tobias Neto reported that he had found what he believed to be a Victoria Cross medal.

Neto has a permit to search the foreshore, and following best practice, he reported the find to London Museum for recording with the Portable Antiquities Scheme.

To learn more about the medal, we searched museum collections and newspaper archives. But we also sought the advice of Mark Smith, an expert in military medals, and David Callaghan, a former director of Hancocks, the company who have made the Victoria Crosses since their introduction.

The medal

The medal itself is bronze, cast in the shape of a cross with a suspension loop projecting from the top arm of the cross.

On one side is a lion with a crown above it and the inscription “For Valour”. The lion represents the soldiers defending the monarch. On the reverse is the date “5 Nov 1854”.

When was the Victoria Cross awarded?

From the date, we know the medal was awarded for bravery shown at the Battle of Inkerman, part of the Crimean War between Russia and the allied forces of Britain, France and the Ottoman empire.

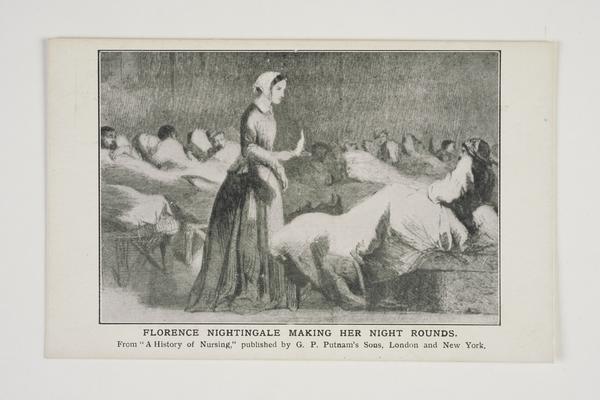

The Crimean War was one of the first to be covered by news reporters, who described the extreme and desperate conditions.

The reports had a big impact back in Britain. Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole headed to the war to help soldiers. And Queen Victoria decided to reward the soldiers’ outstanding acts of bravery. Her Victoria Cross was the first medal which could be awarded to any rank of soldier.

Victoria presenting the Crimean medals in 1855.

Who did the medal belong to?

Most sources suggest 16 VCs were awarded for the Battle of Inkerman. However, a notebook from Hancocks, the makers of the medals, lists the date of the battle a total of 23 times.

Seven of the individuals shown have additional dates listed. Soldiers who perform two VC-worthy actions on different dates receive a thin metal bar attached to the ribbon. Only three bars have ever been issued – none for the Crimean War.

Some sources also record the current locations of the medals. There are two VCs from the Battle of Inkerman where the locations are unknown.

These lost medals belonged to Private John Byrne of the 68th (Durham) Light Infantry and Private John McDermond of the 47th (The Lancashire) Regiment.

It’s also possible that medals’ locations may no longer be accurate. Some may have changed hands, and could be our medal.

Real or replica?

We asked David Callaghan for his expert opinion on whether the medal was authentic. He was unable to say conclusively.

Today you can buy a copy quite easily over the internet. There are fakes around of varying quality and it isn’t always easy to tell the difference.

Victoria Crosses are made from “gunmetal” – metal previously used for a cannon. It’s poor quality and isn’t easy to work with. This makes it difficult to engrave consistently.

Analysis of the metal would be inconclusive as the range of possible positive results is too wide.

Quite simply, more evidence is needed.

“For valour”

Inscription on the Victoria Cross

Private John Byrne

Private John Byrne (1832–1879) was an Irish man who joined the army aged 17.

Byrne won his Victoria Cross for saving a fallen comrade at the Battle of Inkerman in 1854, and for single-handedly fighting a Russian soldier and capturing his musket at the Siege of Sebastopol in 1855. These were two VC-worthy deeds, but the notebook from Hancocks only lists 5 November 1854 next to his name.

Byrne’s story ended in tragedy when he took his own life after shooting a man who insulted the VC. What became of his possessions, his medals? Byrne said that he lost all his property in a fire in Cork, Ireland.

Private John McDermond

The next possibility is Private John McDermond (1832–1868) – a Scottish man who joined his regiment aged 14. He won the Victoria Cross for saving his injured commanding officer, also during the 1854 Battle of Inkerman.

McDermond continued in the army until he was “invalided out” due to an ankle injury. After falling ill with typhus his records are difficult to trace.

The name is relatively common. A John McDermond was in a poorhouse and is buried in an unmarked grave in Paisley, just outside Glasgow. Is this our John McDermond?

“Queen Victoria presented the first Victoria Cross medals to 62 men”

How did the Thames Victoria Cross end up in the River Thames?

Common explanations for how objects end up in the Thames include criminal activity or being deliberately thrown in by the owner. It could have simply been lost, although this seems unlikely.

If we are seriously considering John McDermond or John Byrne, we must ask: when were they in London?

Queen Victoria presented the first Victoria Cross medals to 62 men in Hyde Park on 26 June 1857, marking their sacrifices and bravery during the Crimean War. Neither John Byrne nor John McDermond were present.

Not the end of the story

More research is needed, but, if genuine, the Thames Victoria Cross is an incredibly important medal. There is no higher military honour. And this medal is one of the earliest Victoria Crosses awarded.