Tiny the wonder dog: Rat-killing champion

Around 1850, a Manchester terrier known as Tiny the Wonder was the star of a grisly London show. How many rats could the dog kill in an hour? Take a bet.

St Luke’s, Islington

1850

Tiny but terrible

Of all London’s animals, rats have been among the city’s most troublesome – spoiling food, gnawing through houses and, we now know, spreading disease.

As well as professional rat-catchers, humans have turned to dogs and cats to control them. But Tiny the Wonder’s rat-killing talents were used for entertainment, not pest control.

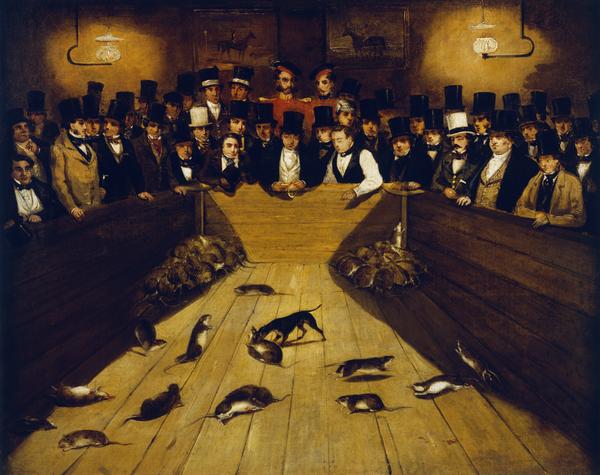

In the middle of the 19th century, in one of several London pubs hosting rat-killing matches, bets were placed on how many rodents Tiny could kill in one hour. The painting above from our collection records the scene.

Attitudes have come a long way since. Most of us agree on the cruelty of watching animals die for our amusement. Manchester terriers are now prized as pets, not killers.

Tiny the Wonder

Tiny was a black and tan Manchester terrier, a breed developed to have a more exciting contest with rats.

He was a very small dog. He weighed only 2.5kg and could wear a lady's bracelet as a collar.

Despite his small size, Tiny was a terror to rats. He could kill one with a single bite.

Who owned Tiny?

The man at the centre of the painting holding a pocket watch is James Shaw. Shaw owned Tiny, and the pub where these contests were held.

The pub was the Blue Anchor Tavern. It’s changed name since – to the Artillery Arms – but can still be found opposite Bunhill Burial Ground, in St Luke’s, Islington.

“over went the dog… and in a second the rats were running round the circus”

Henry Mayhew, 1851

Why did people watch?

Tiny would be timed as he fought the rats, with spectators betting on how many he could kill.

Shaw declared that his dog could kill 200 rats in under an hour. Tiny succeeded twice, on 28 March 1848 and 27 March 1849, "having on both occasions time to spare".

In the painting, the men have fairly blank expressions. But can you imagine the noise in the room? There’s no hiding the fact that this was a violent thing to watch.

Rat-killing dogs like Tiny could become famous. After they died, some were stuffed and displayed as decoration. Souvenir handkerchiefs were sold for people to show they’d been there when Tiny broke a record in rat-slaying.

Rat-catching

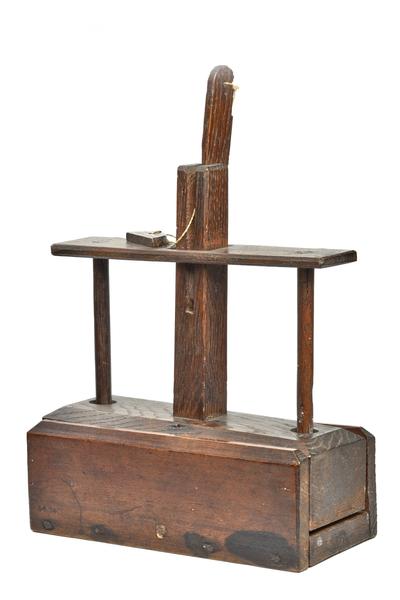

Tiny didn't fight London sewer rats: they were too unhealthy and smelly. Instead, Shaw imported rats from the countryside, keeping up to 2,000 rats in cages under the Blue Anchor.

These animals were sourced by rat-catchers – humans, not terriers, who made their living by trapping or killing rodents. They even sold them as pets.

As London became more crowded in the 19th century, the rat population grew, becoming even more of a problem. Professional rat-catchers were hired to deal with them. One, named Jack Black, became well known and marketed himself as the “Rat destroyer to Her Majesty”. Another, Samuel Province, is said to have taken his own turn in the rat-killing pits, killing dozens of rats.

Animals, entertainment and class

Members of all classes turned out to watch Tiny. On the left-hand side of the painting, the man in the light brown coat is the Count d'Orsay, a French aristocrat and noted dandy – a name given to men known for caring loads about the way they dressed.

Rat-killing in London

The Blue Anchor Tavern wasn’t the only place where people went to watch dogs kill rats, also known as rat-baiting.

In the third volume of his book London Labour and the London Poor, published in 1851, Henry Mayhew described watching “ratting” in the Graham Arms on Graham Street in Islington: “over went the dog,” Mayhew remembers, “and in a second the rats were running round the circus, or trying to hide themselves between the small openings in the boards around the pit.”

An illustration from Mayhew's London Labour and the London Poor shows rat-baiting in the Graham Arms.

Other matches took place at The George in Southwark and the King’s Arms in Drury Lane. As well as watching and betting, people brought their own dogs to these matches – paying to test them out against the rats.

Violent forms of animal-based entertainment – like bear-baiting, bull-baiting and cockfighting – were banned by an act of Parliament in 1835.

But despite the law, rat-killing carried on without much interference. It probably shows that rats were still viewed as a troublesome pest.

Edited version of a blog by Alwyn Collinson, Digital Editor.