Throwing down the gauntlet at coronations

Up until 1821, at the coronation banquet the king or queen’s champion would openly challenge anyone who doubted their right to the throne.

Westminster Hall

1066–1821

Duelling with tradition

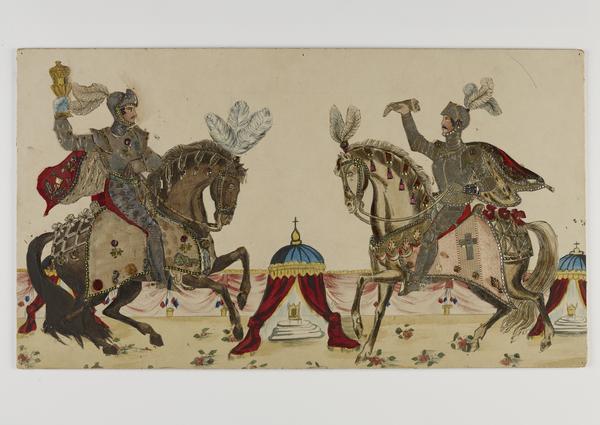

Back in the medieval age, knights could and did settle disputes through trial by combat. This formal process began by throwing an armoured glove – a gauntlet – onto the ground.

If the other person picked it up, the challenge was accepted, and the duel began. The victor won not only the fight, but the argument.

The dukes of Normandy chose selected knights to fight duels on their behalf, particularly when their right to rule was questioned. This started one of the more obscure and romantic rituals surrounding the coronation of British monarchs.

The champion no longer throws down the gauntlet, but they still play a part. At Charles III’s coronation in 2023, the king’s champion carried the royal standard instead.

“an armed knight who shall prove by his body, if need be, that the king is true and rightful heir to the kingdom”

The Scrivelsby grant

The first king’s champion

When William the Conqueror – who was also duke of Normandy – seized the English throne in 1066, he asked his friend Robert Marmion to act as his champion.

Marmion’s role was to literally throw down the gauntlet, openly challenging anyone doubting the new king’s legitimacy to prove their case through armed combat.

In return for putting his life on the line, Marmion was given an estate at Scrivelsby, in Lincolnshire. The grant for this land sets out that:

“The manor of Scrivelsby… [must provide] on the day of coronation, an armed knight who shall prove by his body, if need be, that the king is true and rightful heir to the kingdom.”

Over the centuries, the estate and the role of champion, has remained with Marmion’s descendants. Since 1350 they have been the Dymoke family. Their family motto is the Latin phrase pro rege dimico, a play on their name meaning “I contend for the king”.

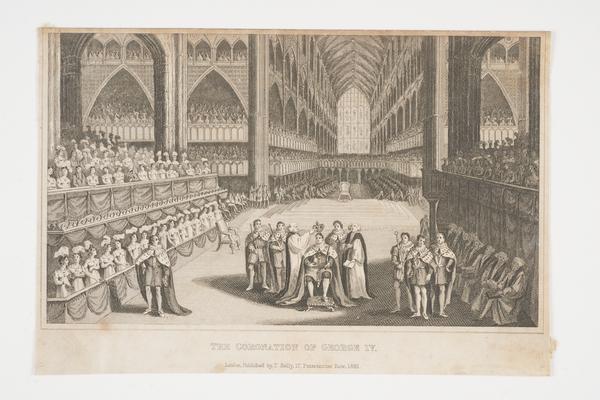

The coronation banquet

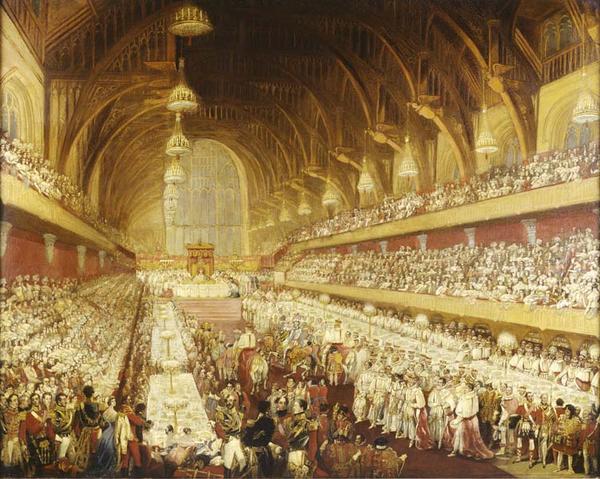

Traditionally, the challenge took place during the coronation banquet, held in Westminster Hall. A painting in our collection shows the scene at George IV’s banquet in 1821.

At the centre of events, Henry Dymoke rides in full armour. He is accompanied by Lord Howard of Effingham (the Deputy Earl Marshal), and the Duke of Wellington (the Lord High Constable), both of whom wear ceremonial robes.

At the far end of the hall, beneath an elaborate canopy, facing the champion, sits King George.

Stretching the length of the chamber are rows of tables where dukes, marquesses, earls, viscounts and barons sit. Above these are two-tiered galleries for the lords’ wives and the landed gentry.

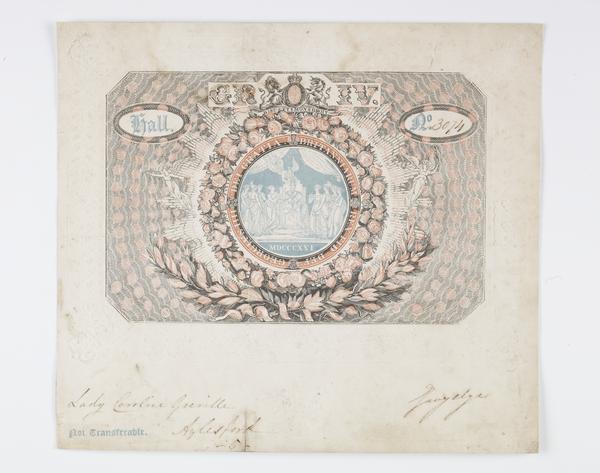

Lady Caroline Greville, whose admission ticket to George’s banquet is in our collection, would have been seated in one of these. Lucky though she may have been to witness the champion’s challenge, Greville probably left hungry. Those in the galleries did not, apparently, get to eat.

Nevertheless, George IV’s banquet was among the most lavish on record. It cost around £250,000, or over £14 million in today’s money.

The dishes were prepared from 23 kitchens, producing 160 tureens of soup, courses of fish, roast venison, beef, mutton, veal and vegetables, moistened with sauce from 480 gravy boats. Attendees washed all of this down with 9,840 bottles of wine and 100 gallons of iced punch. Anyone not satisfied by all of that could help themselves to any of the 3,721 cold dishes provided, which included hams, pasties, seafood and jellies.

A change of tradition

George IV’s coronation was the last time the champion actually performed the ceremony of throwing down the gauntlet.

Ten years later, William IV made significant cuts when he assumed the throne, and the champion was reduced to more modest duties.

At King Charles III's coronation in 2023 there was a champion but no gauntlet-throwing.

At the 1951 coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, the role of champion John Dymoke was simply to carry the royal standard. The banquet no longer takes place in Westminster Hall, and modern menus aren’t quite so extravagant.

For the coronation of King Charles III in 2023, the king’s champion was Francis Dymoke, son of John.

Like his father before him, Francis carried the royal standard, continuing a duty performed by his family for close to a thousand years. It was one of his final acts. Francis, the 34th Lord of Scrivelsby, died less than a year later.