Through the lens of Charlie Phillips

A self-taught photographer, Charlie Phillips was motivated by the desire to document the people and places around him in North Kensington. But his groundbreaking talent went overlooked for decades.

North Kensington

1944

Beautiful portraits of a community

Born in Jamaica in 1944, Roland ‘Charlie’ Phillips moved to west London in 1956. His family settled in Notting Hill, an inner-city neighbourhood in which people from former British colonies in the Caribbean had settled after the Second World War.

Captivated by his surroundings, he honed his skills as a photographer by snapping his friends, family and the wider community. But these sensitive and insightful portraits of home didn’t get the recognition they deserved until decades later.

Now, his photographs of North Kensington are celebrated as a vital window into London’s social and cultural history.

Capturing the North Kensington community

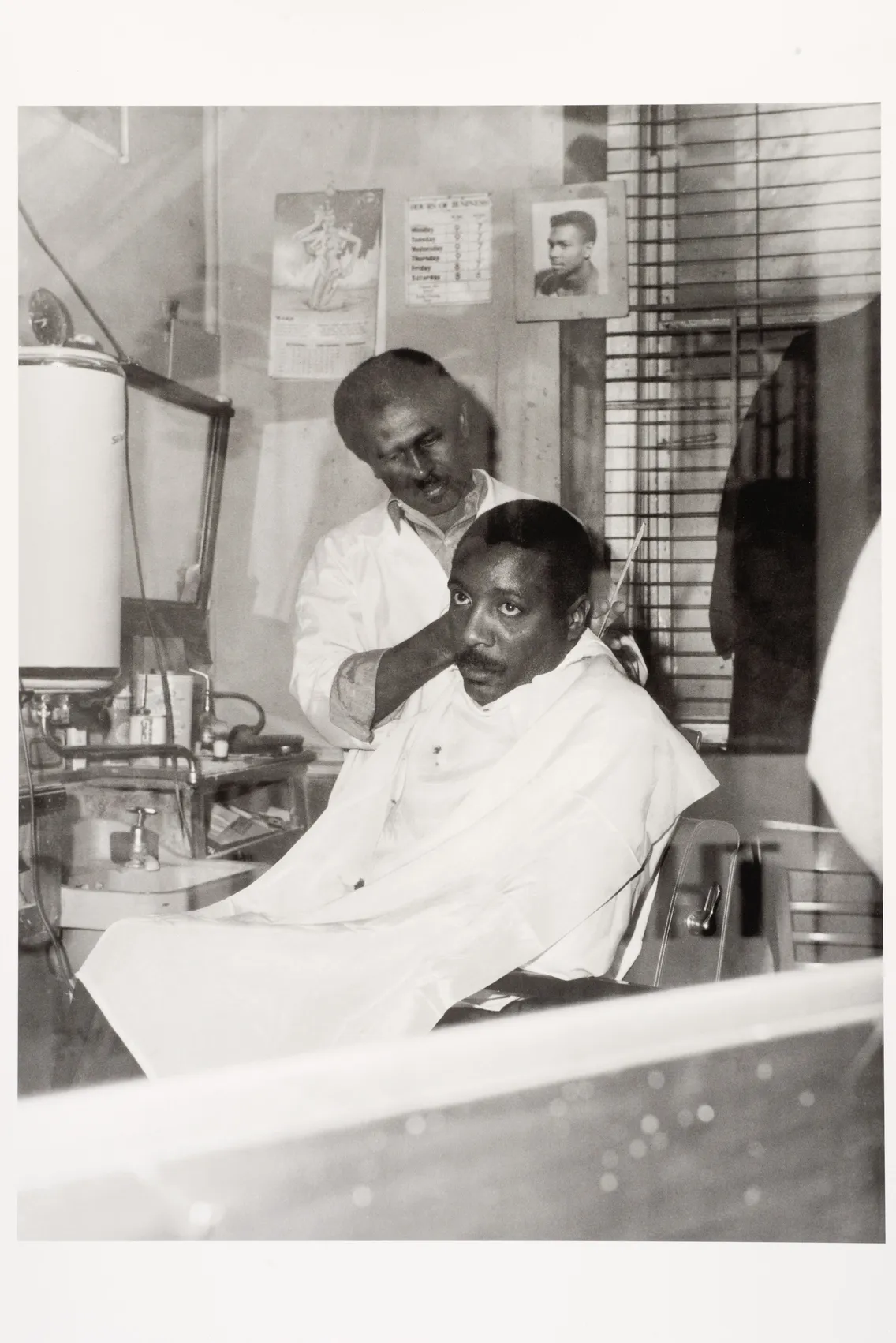

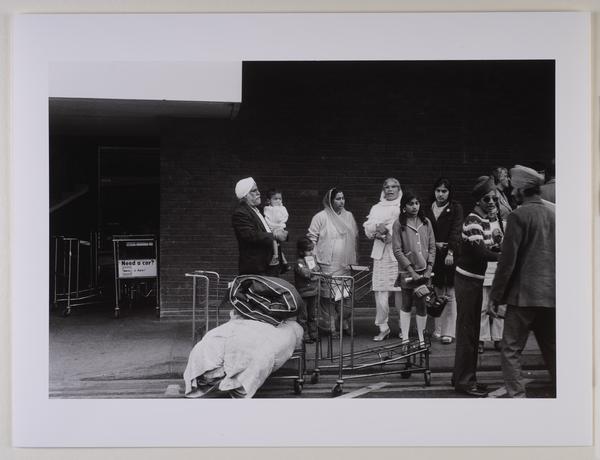

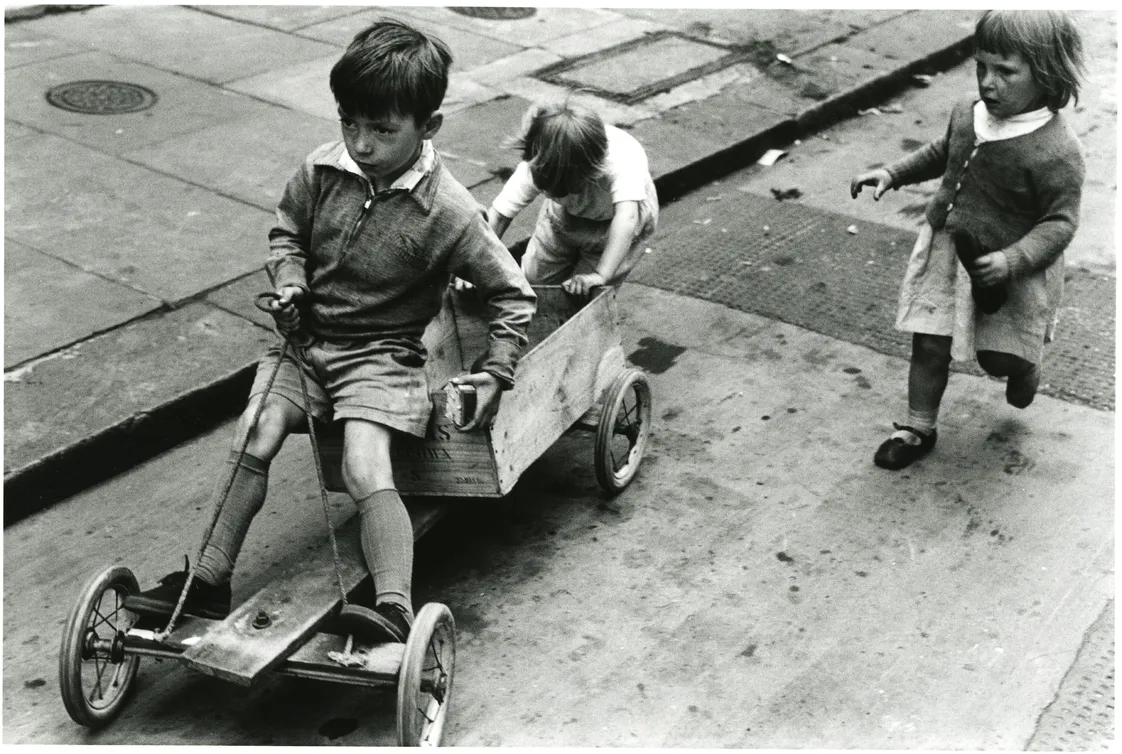

Phillips was profoundly influenced by daily life in North Kensington. In the 1960s and 70s, he photographed the community in and the landscape of the area, particularly the tight-knit network of West Indian migrants.

“It’s not Black history; this is British history, whether you like it or not”

Charlie Phillips

“We haven’t been given a proper platform to show our culture, our side of the story,” Phillips told the Guardian in 2021. “It’s not Black history; this is British history, whether you like it or not.”

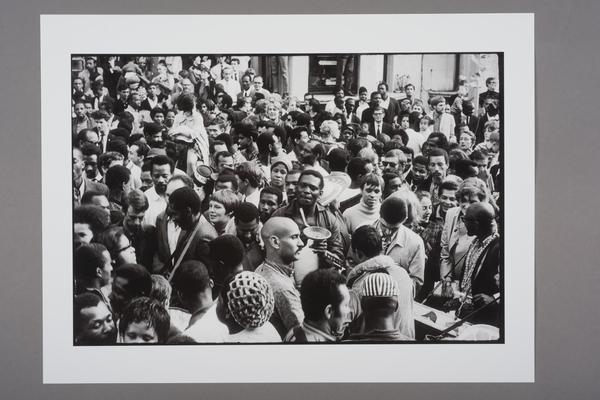

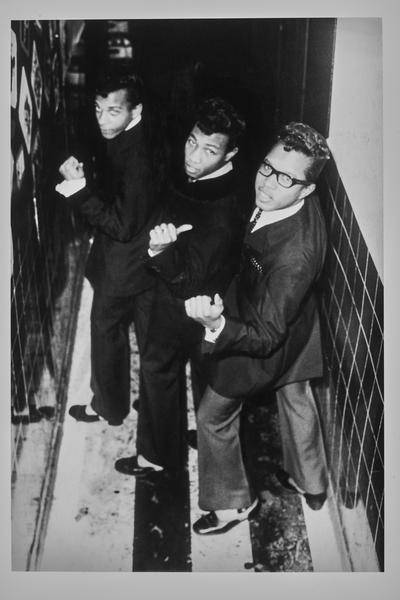

His photographs sketched the joys of daily life: suited regulars at the Cue Club in Paddington, locals down the so-called ‘Piss House Pub’. And they showcased the area’s culture via crowds of revellers at Notting Hill Carnival, and portraits of sound system pioneers like Duke Vin.

Phillips’ North Kensington photographs also reflected the hostilities Black Londoners faced. This included the structural racism that excluded them from public and private spaces. The cramped or run-down houses many were forced to live in.

Around this time, he also began photographing African-Caribbean funerals – and continued to do so for 50 more years. Published in 2014 in a book titled How Great Thou Art, they trace the shifts in the traditions of mourning and celebrating life.

A life on the road

Having spent the 60s attending demonstrations for many different struggles, in 1968 Philips travelled to Paris for a student march. He then hitchhiked to Rome. He lived between London and Italy for six more years.

“I was just a young man hitchhiking all over Europe”

Charlie Phillips

Phillips earned some money snapping the movie stars of Italy’s thriving film industry. He also travelled across Europe working as a photojournalist. “I didn’t have an agent at the time,” he told fellow photographer Martin Parr, “I was just a young man hitchhiking all over Europe.”

His work was published in the likes of Vogue Italia and Life magazine. He also held his first solo show, a photo essay of Notting Hill titled il frustrati, in Milan in 1972.

But back home in London, where he returned in 1974, the reception was less welcome. He struggled to publish his work and get assignments. Editors and galleries didn’t even believe he took his own photographs.

So he abandoned photography. He put his cheffing experience to use and opened Smokey Joe’s Diner in Wandsworth in 1988. He ran the popular eatery for 11 years.

Finding the recognition he deserved

In 1991, Phillips published some of his photographs in the book Notting Hill in the Sixties. These were displayed in the Tabernacle in Notting Hill. At last, his work began to be recognised.

“A visual poet; chronicler, champion, witness of a gone world”

Simon Schama

Two London Museum exhibitions, Through London’s Eyes: Photographs by Charlie Phillips (2003) and Roots to Reckoning: the photography of Armet Francis, Neil Kenlock and Charlie Phillips (2005), also helped put his photographs on the map. You can see some of his photographs in our collection.

Notting Hill Carnival, 1968.

Phillips’s work now increasingly enjoys the attention it deserves. In recent years, his photography has been featured in a range of publications, exhibitions and collections.

Historian Simon Schama described him in 2015 as “a visual poet; chronicler, champion, witness of a gone world… One of Britain’s great photo-portraitists.” The acclaim was a long time coming.