The Stone Age skull rescued from the River Thames

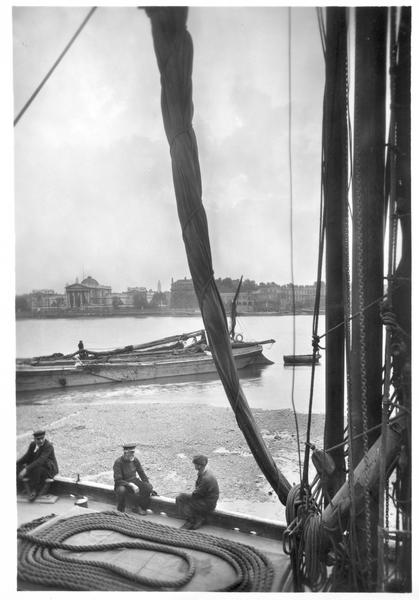

While searching the shore of the River Thames in 2018, a mudlark discovered part of a Neolithic skull, some of the oldest human remains ever found there.

River Thames

3,600 BCE

This page contains content some people may consider sensitive, or find offensive or disturbing. Understand more about how we manage sensitive content.

A Londoner from long before London

Mudlarks are amateur enthusiasts, licensed by the Port of London Authority, who scan the banks of the River Thames looking for interesting objects. They find some miraculous things – and this is one of the best.

At first, police investigated the fragment. But the bone was found to be 5,000 years old – if this was a victim of crime, it was beyond the police’s reach.

The bone is now part of our collection at London Museum. It’s an extremely rare find from a time when people in this area were just beginning to abandon nomadic life for farming.

In their rural landscape, the people saw the Thames as a spiritual river. As tribute they threw precious objects into its waters, including human remains.

What did the mudlark find?

Only a small part of the skull was recovered – the frontal bone, which makes up part of the forehead and the top of the eye sockets.

It was enough for osteologists who studied it to tell that this skull belonged to a man over 18 years old.

A Neolithic crime scene?

The concerned mudlark who discovered the bone first contacted the Metropolitan Police – as is required whenever human remains are discovered.

Detectives searched the area and, not knowing how old this fragment was, began an investigation.

Radiocarbon dating soon revealed that the bone dated back to the Neolithic period. The police then donated it to London Museum.

Radiocarbon dating

The radiocarbon dating showed the bone is about 5,600 years old – so, from around 3,600 BCE.

That places it in the Neolithic period, also called the New Stone Age. This period began about 6,000 years ago, as farming began to develop.

The Neolithic ended in northern Europe when it became common for people to use metal, the period we call the Bronze Age. In Britain the Bronze Age started in about 2,000 BCE.

London in the Neolithic

Living in the area that would one day become London, this Neolithic man would have seen a very different landscape than the one we are used to.

The Thames was much wider and shallower than it is today, and bordered by extensive mudflats and woodland.

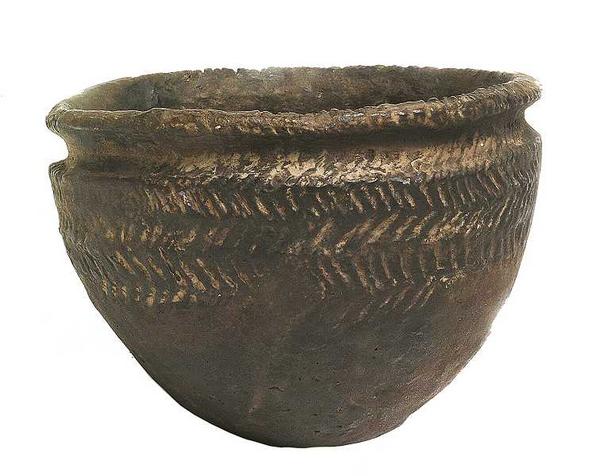

Traces of human activity dating to between 3,500 and 4,000 BCE have been found along the floodplain of the Thames, mainly flint tools, flint weapons and fragments of pottery.

“Offerings to the Thames included human remains”

How did people live in the Neolithic?

The people living on the future site of London lived a semi-nomadic lifestyle herding animals. They mixed this with hunting and gathering food, and increasingly, more settled farming.

Rare evidence of this more rooted lifestyle was found at Runnymede Bridge in Surrey. At that site, the remains of at least one large rectangular wooden house were discovered. This was built near the river between 3,900 and 3,500 BCE, the same period the human bone dates to.

The area around the house contained cattle bones, broken pottery and flint tools. People living in these houses were probably large family groups who also grew some crops. Burnt grain has been found at a site near Canning Town, east London dating to between 3,900 and 3,300 BCE.

Why was a skull found in the River Thames?

At that point in time, over 5,000 years ago, the river provided a wide range of natural resources, such as reeds, clay and food. People also travelled along the river, making it a communication and transportation link.

Increasingly, Neolithic people seem to have seen the Thames as a sacred river, perhaps similar to the Ganges in India. Offerings to the Thames included human remains, pots, bone and antler tools, as well as flint and stone axes.

The largest and most beautiful axes and maces, often made from rare, exotic stones, seem to have been deliberately chosen as gifts to the river. Some had been traded from as far away as Ireland, Cornwall and mainland Europe. A jade axe in our collection came from the Italian Alps.

Could this Neolithic man's body have been another offering to the sacred river?

There are other explanations. The changing course of the river and the streams which led into it washed over many early settlements. The water is sure to have disturbed many Neolithic graves.