The New Cross fire

In 1981, a fire at a house party in New Cross, south-east London, killed 13 young Black people. Many suspected a racist attack, but nobody has ever been charged.

New Cross, south-east London

18 January 1981

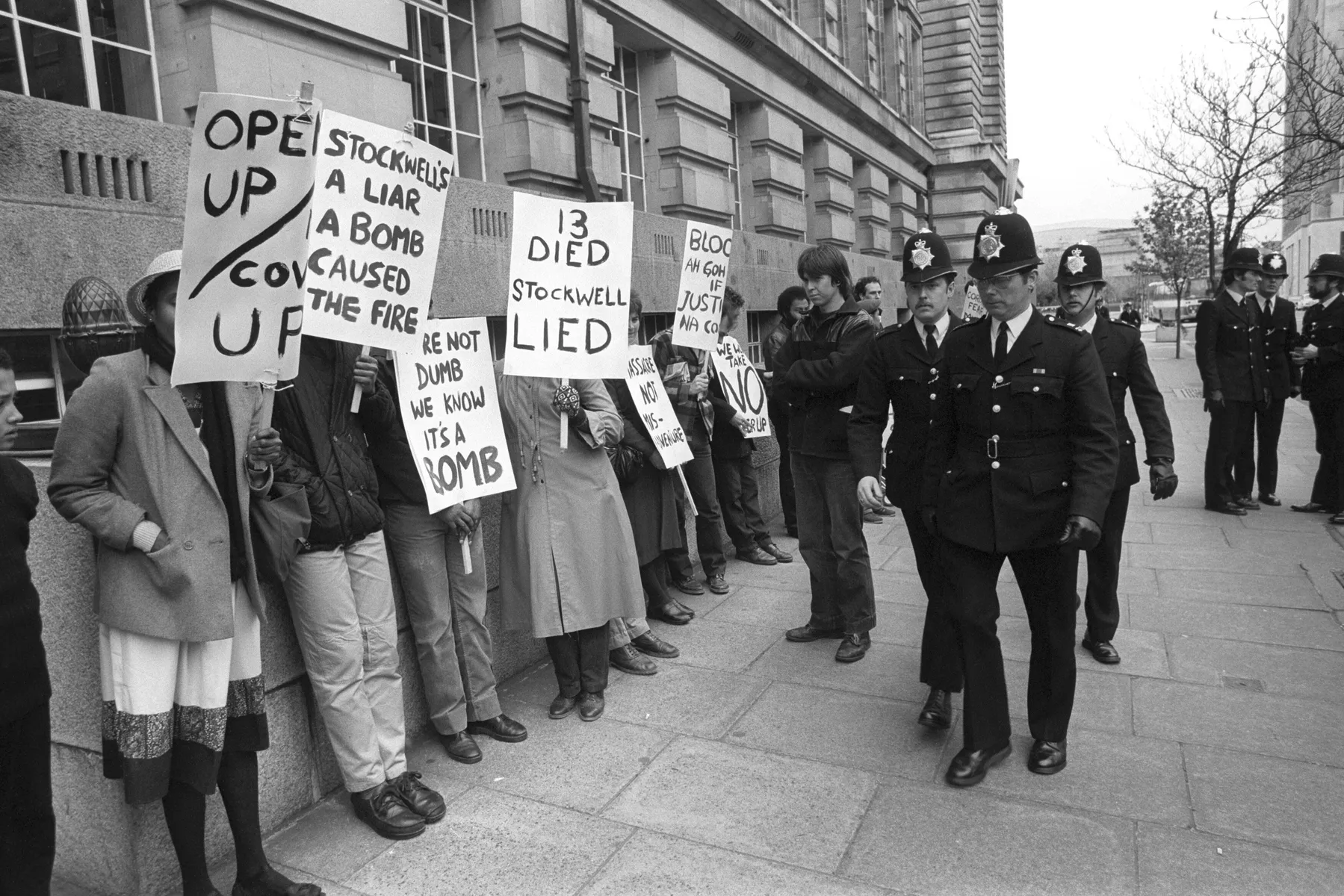

Protestors from the New Cross Massacre Action Committee gather at County Hall to challenge the inquest into the fire.

A tragic catalyst for the Brixton Uprising

During the 1970s and 1980s, Black British people (from the African-Caribbean and African diasporas) faced aggressive racism and police discrimination.

That racism fuelled suspicions that the New Cross fire was a petrol bombing.

The police investigation failed to find answers, and was criticised for quickly ruling out a racial motive. The local community were also angered by the limited response from the press and politicians.

A mass march was organised. And a month after the fire, the tension spilled over in the 1981 Brixton Uprising.

In 2004 a new inquest found that the fire was probably started deliberately inside the house, and not by a petrol bomb. But it also said there wasn’t enough evidence to be sure it was arson. Meaning those affected still don’t know the truth.

The fire

On 18 January 1981, around 100 people, the majority of whom were Black, were celebrating the birthdays of two teenagers at a house party at 439 New Cross Road.

A fire started on the ground floor and spread quickly. Those trapped upstairs jumped from windows to escape.

A total of 13 people died in the fire. The youngest was 14 years old. More than 50 were injured. A 14th person took their own life two years later.

A backdrop of racism

There were strong reasons to suspect a racist attack.

The 1970s and early 1980s were a time of severe racial tension. Photos from our collection show racist graffiti sprayed on walls and doors in multicultural areas.

A far-right anti-immigrant party, the National Front, gained popularity by blaming high unemployment and crime on Caribbean and South Asian people – communities who’d been encouraged to settle in Britain to help ease its labour shortage.

In 1977 NF supporters fought with residents and anti-fascist groups at the Battle of Lewisham. In 1979, a National Front meeting in Southall, an area with a large settled South Asian population, also led to violent protests.

And in the years before the New Cross fire, other fires in flats, community centres and theatres across south London were also suspected to have been racist attacks.

The police

Black Londoners also faced discrimination and violence from the Metropolitan Police, which meant many didn’t trust the authorities.

The “sus” law allowed police to stop, search and arrest anyone they thought was intending to commit a crime. The police used it to harass Black and South Asian people.

In 1977, the police raided more than 50 houses in Lewisham and New Cross, arresting 21 young Black men as part of an anti-mugging campaign. It caused outrage among the community, while the National Front seized on it to stoke local tensions.

“13 dead, nothing said”

The investigation

After the New Cross fire, the police began a murder investigation, but ruled out a racial motive, quoting a lack of evidence. Instead they focused on whether a fight within the party had caused it.

In response, family members and activists set up the New Cross Massacre Action Committee. The group raised funds, supported the families, protested against the police’s mishandling of the investigation and pushed for accurate media coverage.

The 1981 coroner’s inquest into the cause of death returned an open verdict – meaning nobody was found to be responsible for the fire.

The press and politicians

Relatives and activists were frustrated by the media reaction to the tragedy, and the lack of national attention it received.

Press coverage often blamed people at the party. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher took five weeks to respond to a letter condemning the government’s lack of action.

“13 dead, nothing said” was the slogan of those who campaigned for justice.

Uprising

Angry at what they saw as a police cover-up, activists including Darcus Howe organised the National Black People’s Day of Action on 2 March 1981. An estimated 20,000 people from all across the country marched through central London.

But this didn’t dissolve the tension that had built up between police and the Black community in south London.

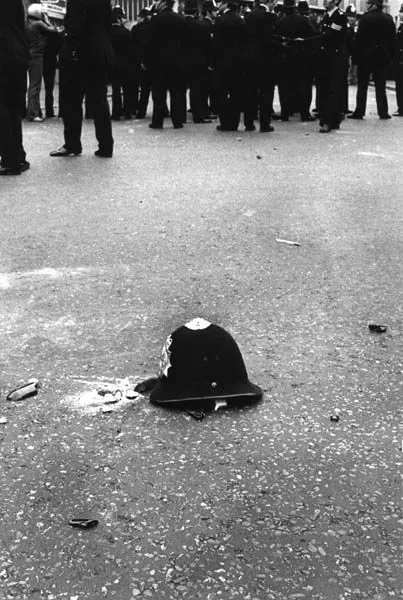

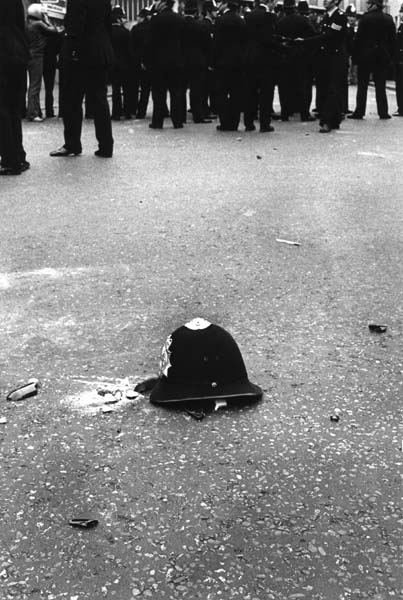

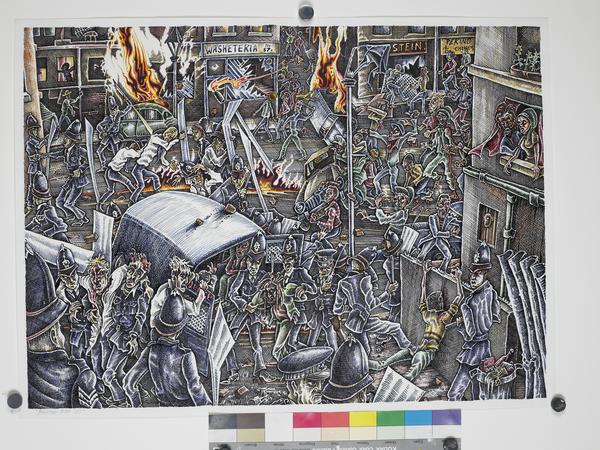

A month later, the Brixton Uprising broke out. Also known as the "Brixton riots", it was triggered by reports of police brutality. Over three days, protestors fought with police and burned buildings. More than 300 people were injured.

The 1981 Brixton Uprising came only months after the New Cross fire.

Second inquest

Many people refused to accept the first inquest’s verdict. Songs and poems were written about the tragedy, including poet Linton Kwesi Johnson’s New Craas Massahkah, Benjamin Zephaniah’s 13 Dead, and Johnny Osbourne’s 13 Dead (Nothing Said).

439 New Cross Road today. A blue plaque marks the site of the tragedy.

For decades, the New Cross Fire Families' Committee campaigned for a second inquest.

A new inquest was started in 2002, in part because of the changing attitudes of the Metropolitan Police following the 1993 murder of Stephen Lawrence.

The results were published in 2004: another open verdict, meaning no definitive answers.