The life story of Mary Prince

After walking to her freedom in London in 1828, Mary Prince narrated her experiences of enslavement in The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave.

1788 – unknown

A vital voice in the liberation of enslaved people

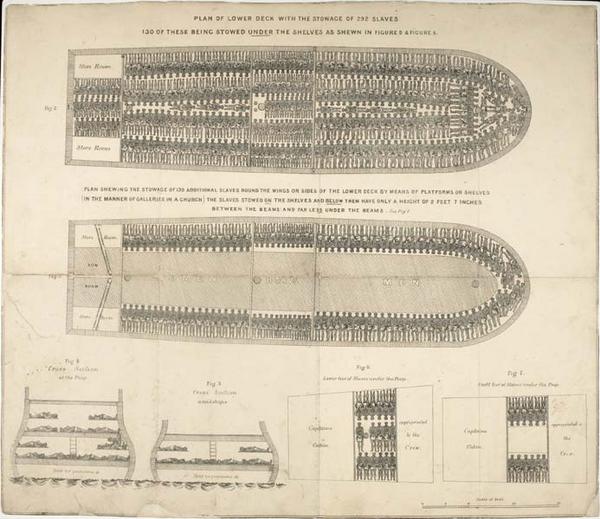

Mary Prince was born to enslaved parents in the West Indies in 1788. She spent most of her adult life enslaved, going, in her words, “from one butcher to another” in Bermuda, Grand Turk Island and Antigua. She was treated cruelly and violently – a typical experience of enslaved people in the British empire.

We know about Prince’s life because she retold it in her book, The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave. Related by Herself. Published in 1831, Prince’s story drew attention to the continued horrors of the British trade in enslaved Africans in the region. It was the first narrative of a Black woman to be published in Britain.

How Mary Prince came to London – and walked to her freedom

In 1828, Prince was brought from Antigua to London to work as a servant for her abusive enslavers of 10 years, the Woods. She’d made a number of attempts to purchase her freedom from them. But they repeatedly refused. She had to leave behind her husband, a formerly enslaved man named Daniel James.

In London, Prince’s health was worsening, and the chronic inflammation and pain in her limbs meant she struggled to carry out the tasks imposed on her by the Woods. They threatened to throw her out onto the streets.

“at last I took courage and resolved that I would not be longer thus treated”

Mary Prince, 1831

So she chose to walk out: “at last I took courage and resolved that I would not be longer thus treated, but would go and trust to Providence,” her book recounts. Prince found refuge in the Moravian Mission in Hatton Garden (now in Holborn), a Protestant church of which she became a follower in Antigua.

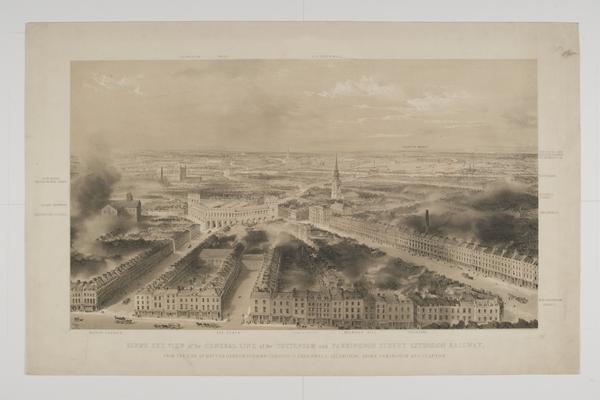

Bird's eye view of Hatton Garden road on the left-hand side looking towards north London.

Fighting for her freedom

Prince later found work and a home with Thomas Pringle, secretary of the London abolitionist group the Anti-Slavery Society.

Pringle also tried to get her enslaver John Adams Wood Jr. to formally free her. He even submitted a petition to Parliament in 1829. But again, this was unsuccessful. The Woods returned to Antigua that same year.

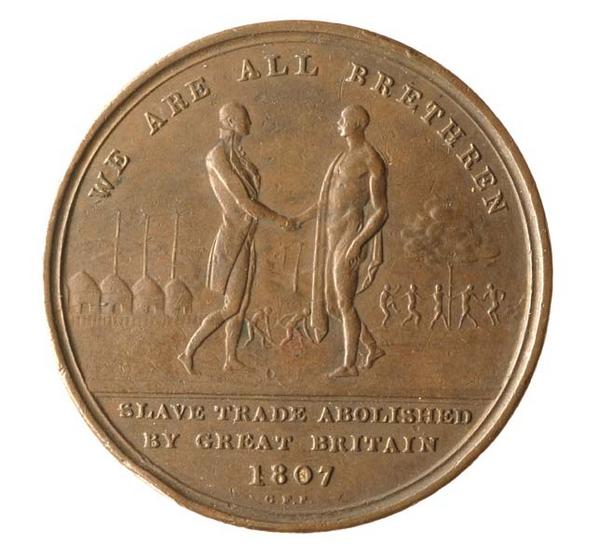

In London, Prince was technically a free woman. The 1807 Abolition of the Slave Trade act had made it illegal for British subjects to ‘buy’ and ‘sell’ enslaved people throughout the British empire. But if she were to return to her husband in Antigua, she would be re-enslaved. Enslaved people in most British colonies like Antigua were not freed by law until after the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act.

‘The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave’

While living with the Pringles, Prince created her autobiography. She told her life story to writer Susanna Strickland, who compiled the text. Pringle edited the final document. The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave. Related by Herself was published by Prince in 1831.

The book tells of the horrors of slavery. It includes vivid descriptions of the violence inflicted upon her and other enslaved people by their enslavers. We also see her strength and resilience – how she scrimped, saved and asserted her right to buy her freedom, and how she stopped one of her enslavers beating his daughter in a drunken fury.

In 1833, John Adams Wood Jr. took Pringle to court claiming The History of Mary Prince contained false information and damaged his reputation. Prince herself appeared in court as a witness to defend her own story. The judge ruled that Prince’s book was exaggerated and her enslaver won the case.

Prince the abolitionist

The History of Mary Prince galvanised the movement towards the full emancipation of enslaved people in the British empire and its colonies. It was widely read and printed three times in 1831.

“I have felt what a slave feels, and I know what a slave knows”

Mary Prince, 1831

It includes powerful rallying cries for abolition: “I have felt what a slave feels, and I know what a slave knows; and I would have all the good people in England to know it too, that they may break our chains, and set us free.” But scholars have debated the extent to which Prince’s story was shaped by Pringle and Strickland, two white abolitionists, to further the cause in the English reading public.

Prince also wrote a letter to Parliament asking them to free all enslaved people in the Caribbean. This made her the first woman in Britain to petition to Parliament.

We don’t know much of what happened to Prince after 1833, whether she died in Britain or returned to Antigua. No known images of her survive, either. But her story remains a powerful testament to the strength and resistance of enslaved people across the West Indies.