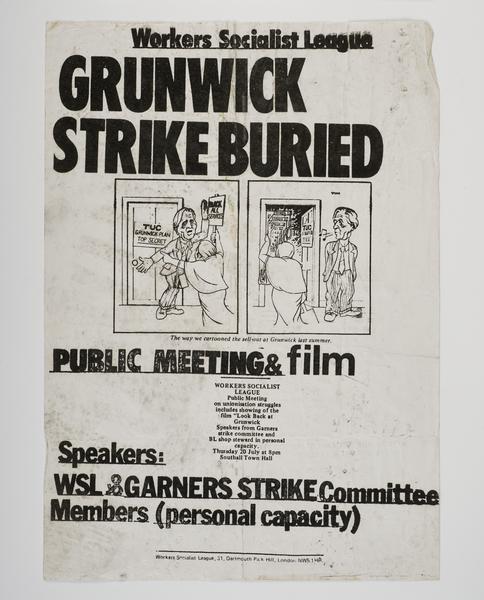

The Grunwick strike, 1976–1978

In the relentless heatwave of summer 1976, workers at a north-west London film processing factory took to the streets to protest poor working conditions. Their cause won the support of thousands.

Willesden, Brent

1976–1978

A two-year battle for rights, dignity and respect

In the days before digital cameras, you’d snap your holiday photos on rolls of film and send them off to be processed into prints. The Grunwick Film Processing Laboratories, in the suburbs of Dollis Hill, Brent, was one such place you’d post your memories to.

In August 1976, 137 workers at the factory walked out over racism, low pay, lack of trade union recognition and degrading working conditions.

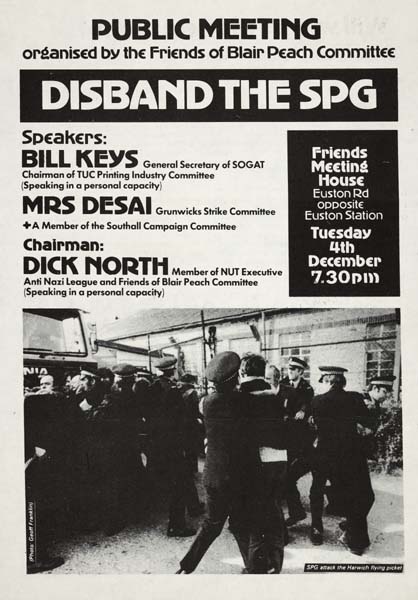

The dispute was mobilised by the factory’s many recently settled migrant employees, most of them women with South Asian heritage. And it was spearheaded by Indian-born Jayaben Desai, an employee who became a leading figure in the fight for workers’ rights.

The strike was one of the longest in British history. It eventually ended in defeat for the strikers. But the dispute marked a turning point in trade union solidarity with migrant workers and black workers (a term used from the 1960s to the 1990s to describe all people of colour) in Britain.

Jayaben Desai.

Grunwick’s workforce were subject to tough conditions

Grunwick staff worked long hours for low wages. Overtime was compulsory and often imposed without notice. And this workforce, which was predominantly made up of women, worked under the controlling and racist atmosphere created by their male managers. They even had to ask for permission to use the toilet.

“We used to work out of fear,” one former employee remembered.

Many employees had moved to Britain from East Africa

Some of the employees were of African-Caribbean origin. Most (around 80%) were of South Asian origin, and many were from ex-British colonies in east Africa like Kenya and Uganda. Many had settled in East Africa under colonial rule, living there for generations, and held British passports.

When these countries gained independence from Britain in the late 1960s and 1970s, some South Asian people chose to settle in Britain. Those from Uganda were forced to leave in 1972 and were banned from taking valuable possessions with them. They came to Britain with very little.

In east Africa, many South Asian people were successful business owners or worked in well-paid professions like trading and the civil service. Desai married the manager of a tyre factory from Tanganyika (part of present-day Tanzania) and enjoyed a comfortable lifestyle there.

But as these jobs were inaccessible to them in a largely hostile British society, Desai and thousands of others were made to take on factory and manual work in order to survive.

1976: the workers walk out

On 23 August 1976, six employees started a protest outside the factory against their demeaning treatment. Others in the factory soon joined them on the picket line. Desai said: “it is not so much a strike about pay, it is a strike about dignity”.

Jayaben Desai and Engineering Union leader Hugh Scanlon are among those on the picket line outside Grunwick.

Desai and the strikers joined the trade union APEX (Association of Professional, Executive, Clerical and Computer Staff) and demanded the right for their union to be recognised. Grunwick manager George Ward refused and the 137 workers were later sacked.

They win the support of trade unions

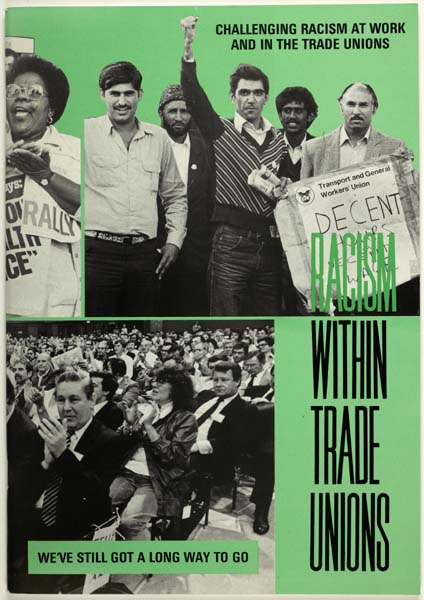

In the 1970s, women workers and workers of colour found it difficult to win support from white male-run trade unions. Many felt the unions were racist. They failed to act on workplace discrimination and denied them the same support offered to white workers.

But after months of picketing, the Grunwick workers’ cause began to be supported by other trade unions, such as the National Union of Mineworkers and the Trades Union Congress (TUC).

Other trade union groups joined the Grunwick strikers in protest.

Members of the Union of Post Office Workers even stopped delivering post to the factory in protest, making a significant dent in Grunwick’s trade. But this action was later ruled as illegal.

“A defeat for us would be a defeat for the whole working class”

Grunwick Strike Committee poster, 1977

And the strike gained momentum

Under Desai’s energetic and inspirational leadership, support for the strikers continued to grow.

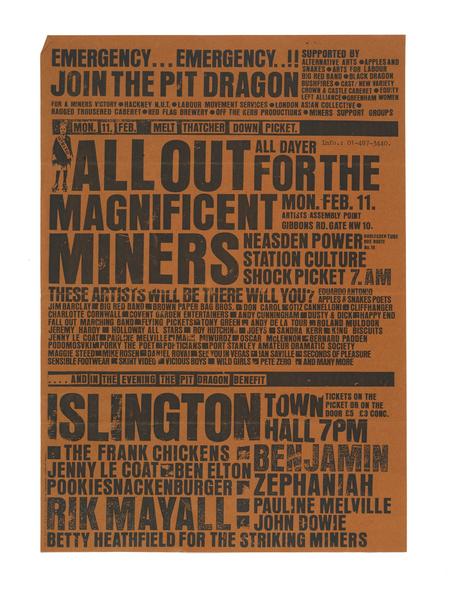

Feminist groups, anti-racist groups and socialist organisations such as the Socialist Workers Party also joined the picket lines. In 1977, crowds at the picket line swelled to up to 20,000 on some days. “A defeat for us would be a defeat for the whole working class,” rallied one campaign poster.

The police sent out large numbers of officers to control the crowds and defend workers crossing the picket line. They harassed and sometimes violently clashed with protesters.

On one November day, 243 people were treated for injuries and 12 had broken bones. Around 550 strikers and supporters were arrested over the two years. That was the highest number detained in an industrial dispute since the 1926 General Strike.

Grunwick refused to back down, and the strike failed

After two long years on the picket line, the Grunwick strike ended in defeat. APEX and the TUC withdrew their support once they felt the dispute couldn’t be won.

The determined Desai led a hunger strike outside the TUC headquarters in Bloomsbury – but even that couldn’t change their minds. “Trade union support is like honey on the elbow,” she said. “You can smell it, you can feel it, but you cannot taste it.”

The Grunwick management never gave the striking workers back their jobs. Nor did they recognise the union.

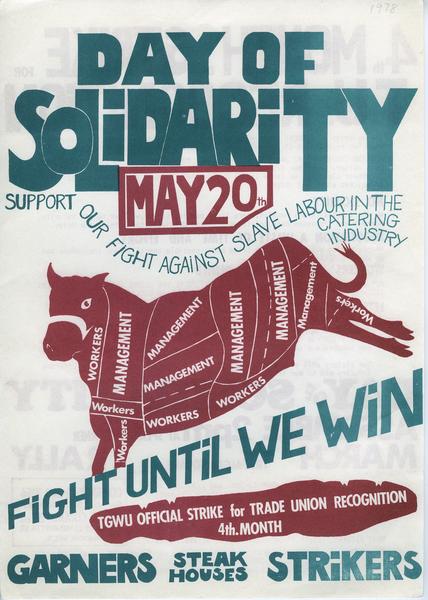

But the strike directly inspired other industrial movements, including a dispute over pay conditions and union recognition at Garners Steak Houses across London from 1978–1979.

“We have shown that workers like us, new to these shores, will never accept being treated without dignity or respect”

Jayaben Desai

And it was an early example of solidarity by trade unions and the wider public in support of women and migrant workers.

In the final strike meeting, Desai said: “We have shown that workers like us, new to these shores, will never accept being treated without dignity or respect. We have shown that white workers will support us.”