The Great Smog of 1952

In 1952, London experienced five terrifying days known as the Great Smog – one of the deadliest recorded episodes of urban smog.

Across London

5–9 December 1952

Five days of pollution which killed 12,000

Air pollution has blighted London for hundreds of years, getting significantly worse as the city grew into a modern, industrialised city in the 18th century.

Like the 19th-century Great Stink, the five days of the 1952 Great Smog were so exceptionally bad that it became a turning point. The government was forced into action, passing the 1956 Clean Air Act to combat the city’s air pollution.

London’s pollution would never be so visible again, but the problem didn’t stop in the 1950s. Today’s pollution – caused mainly by road vehicles – remains severe and deadly.

Foggy London

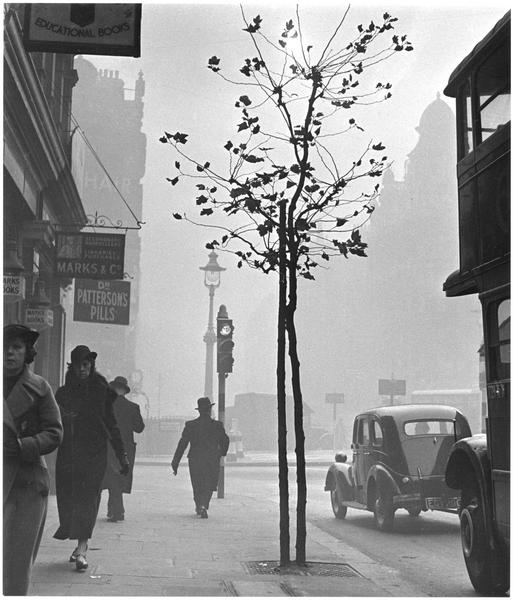

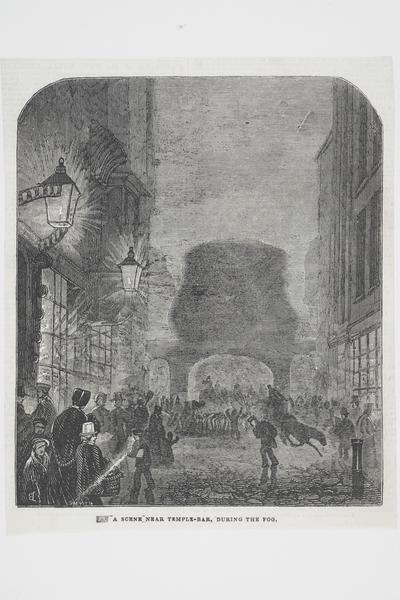

London was known for its foggy atmosphere during the 19th-century Victorian era. However, this was actually smog, not fog – a dangerous mixture of fog and sulphur dioxide produced by burning coal.

In moist air sulphur dioxide is converted into a more dangerous liquid – sulphuric acid.

High levels of pollution persisted into the 20th century. Londoners regularly experienced “pea-soupers” where thick yellow or brown smog filled the air, making it hard to see and difficult to breathe.

“People who went outside couldn’t see their own feet”

Why was London so polluted?

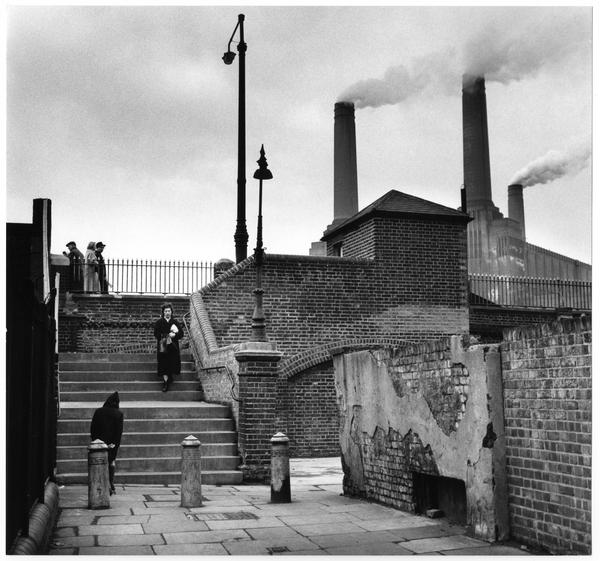

In the 1950s Londoners mainly heated their homes by burning coal. East London was still home to factories, and coal-burning power stations like Battersea and Lots Road lined the Thames. All produced large amounts of smoke.

Smoky, diesel-fuelled buses, which had recently replaced the electric tram system, added more fumes to the problem.

What caused the Great Smog?

Both the weather and the economic situation in December 1952 made London’s regular pollution much worse.

November and December of 1952 were bitterly cold. Londoners lit their coal fires to keep warm, and there’s evidence that the coal they burned was more polluting than usual.

Higher quality, less polluting coal was in shorter supply, because the country’s weak economy required this more valuable coal to be sold abroad.

During December a weather formation called an anticyclone trapped the coal smoke, while an easterly wind carried more polluted air to London from Europe.

As a result, dense smog covered London between 5–9 December 1952.

How did it affect Londoners?

As the sun rose on Friday 5 December 1952, Londoners behaved as normal. But as the day progressed, the smog became thicker. It became clear that this wasn’t usual.

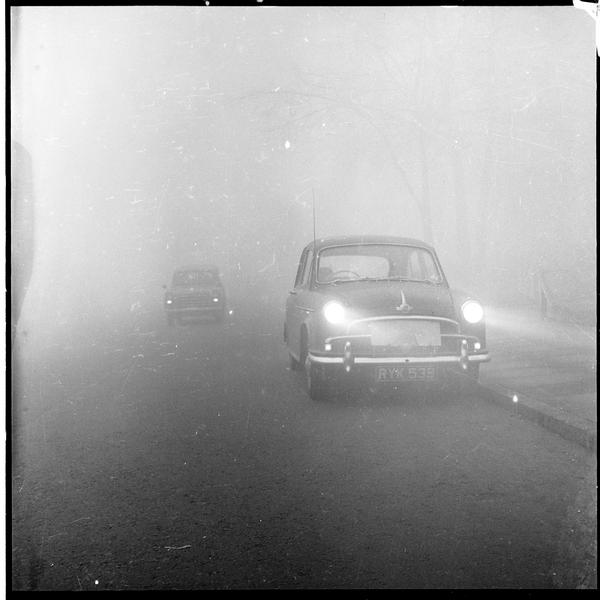

The smog worsened, lasting for five days. People who went outside couldn’t see their own feet. Smoke particles covered their clothes. Cars were abandoned in the road and at one point the majority of buses were cancelled.

The smog even penetrated into people’s homes, creeping through cracks and under doors.

The poisonous air made it difficult to breathe, especially for anyone with an existing lung condition, and people began to feel ill.

It’s estimated that 4,000 people died across the five days. Death rates reached their highest level since the so-called Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918–1919. More died afterwards from the smog’s long-term effects, bringing the estimated death toll to 12,000.

Two years after the Great Smog, this banner on Gloucester Terrace, Paddington demands "clean air".

What was the solution?

At first, the government wasn’t convinced pollution was the cause of the deaths, but eventually action was taken.

In 1954 the City of London Corporation banned smoke in the Square Mile.

In 1956 the Clean Air Act was passed by Parliament, creating smoke-free areas across London and regulating coal-burning in homes and factories.

The problem didn’t go away overnight. Another Clean Air Act was passed in 1968. Slowly coal was replaced by gas, and power stations were moved out of London.

Could it happen again?

London’s modern day pollution is mainly caused by road vehicles, whose fumes aren’t as visible as coal smoke.

But London’s air is still dangerous. It has regularly been above legal limits, and a 2019 study found that pollution contributed to roughly 6,000 excess deaths in the capital that year.

Recent efforts to improve the problem include London’s Ultra-Low Emission Zone (ULEZ), first introduced in 2019, which charged drivers of the most polluting vehicles.