The Great Plague of 1665

The Great Plague of 1665 killed 20% of the UK’s population, and an estimated 100,000 Londoners, just one year before the Great Fire of London.

Across London

1665

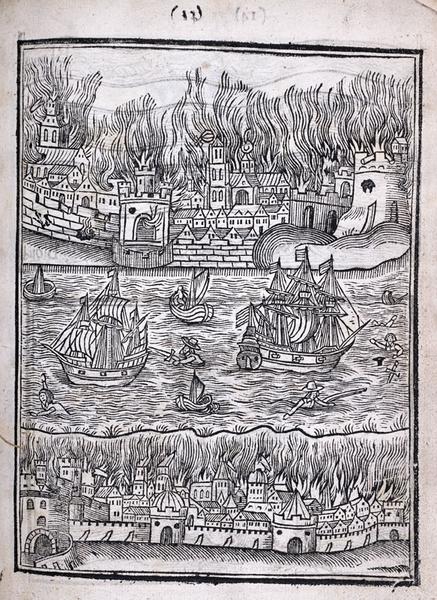

This 1666 broadsheet shows nine scenes from the 1665 Great Plague, including Londoners fleeing by boat, corpses carried through the streets and Londoners returning to their homes.

London’s last major bubonic plague epidemic

Plague was a regular problem in the early 17th century – epidemics hit London in almost every decade up to the 1660s. But 1665’s outbreak was on a different scale, affecting all towns within 10 miles of London.

Covid-19 has left us all with a tragic understanding of what it’s like to live through a pandemic in the 21st century. How does that compare to the last major plague epidemic?

“Lord! How empty the streets are and how melancholy”

Samuel Pepys, October 1665

What is plague?

Plague is an infectious disease which takes two main forms: bubonic plague and pneumonic plague.

The most common – bubonic plague – causes large swellings on the body, also called buboes. The disease is caused by the Yersinia pestis bacteria. It’s spread by the bites of infected rat fleas.

How did Londoners respond to the plague?

Those who could afford to escaped from the city. That included King Charles II and most of his court, who swiftly left for Oxford.

Most business stopped. Poorer Londoners tried to flee, but were often turned back by people in the villages surrounding the city.

Illustrations from the time show authorities shutting up the houses of the infected. If one family member fell ill, the rest were locked in too.

Bells rang in the streets to warn that infected bodies were approaching, and bonfires were lit to fend off miasmas, the bad air blamed for spreading the plague. Without today’s medical understanding of the disease, cats, dogs and poisoned wells were also blamed for its spread.

The diarist Samuel Pepys described what he saw in 1665: “Lord! How empty the streets are and how melancholy, so many poor sick people in the streets full of sores… in Westminster, there is never a physician and but one apothecary left, all being dead.”

How many people died in the Great Plague?

An estimated 100,000 Londoners died from plague in 1665, roughly one fifth of the UK’s population.

Parish clerks kept weekly records of deaths, called Bills of Mortality. Just as with Covid-19, we can use the numbers to see how infections grew, and eventually faded away.

The records aren’t perfect though. A lack of understanding and poor data led to mistakes and under-reporting. The clerks didn’t count the deaths of Quakers, Anabaptists and Jews either, and often blamed other diseases, such as "spotted fever".

For comparison, between March 2020 and May 2023, 227,000 people died in the UK from Covid-19. And the Black Death? Estimates are difficult, but some historians argue that plague killed half of Europe’s population in the mid-14th century.

Did the Great Fire of London end the plague?

The short answer is no.

Some people think that the fire killed rats and fleas spreading the disease, or that it cleared the dirty, crowded housing where plague thrived. Neither idea matches the evidence.

The disastrous Great Fire of London came only a year after the Great Plague hit the city.

The 1666 Great Fire didn’t destroy the areas most affected by the plague, such as Whitechapel, Clerkenwell and Southwark.

As for housing – yes, new rules required outside walls to be made from brick, but there weren’t any real improvements to hygiene.

Instead of seeing one clear turning point, the numbers suggest a slow decline in deaths, starting in the winter of 1665. By February 1666 even King Charles II felt safe enough to return.