Stanley Green: The protein man of Oxford Street

Stanley Green became known as Protein Man for his 25-year campaign to get people eating less protein, which made him a recognisable London character.

Oxford Street

1915–1993

Less Lust From Less Protein

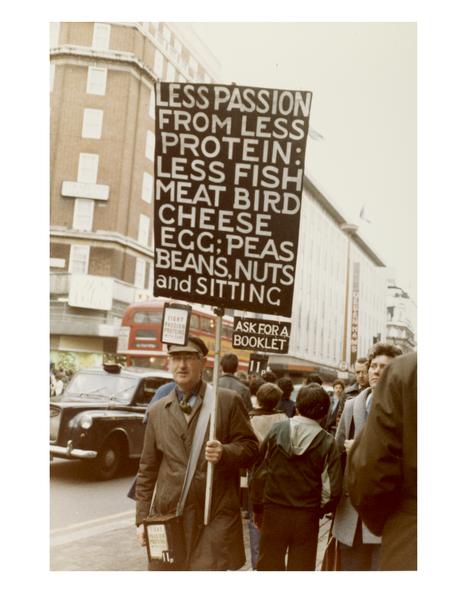

From 1969 until his death in 1993, Stanley Green was seen almost daily in Oxford Street, weaving through the crowds, sign in hand.

Too much protein, he believed, caused chaos by making people uncontrollably passionate.

People may not have agreed with his message, but over time, he became another well-known part of London’s personality – as recognisable as its black cabs and as persistent as its pigeons. His diaries, signs and booklets were donated by his brother after Green died, and are now part of our collection.

Birth of a campaign

Stanley Green was born in Tottenham in 1915. He never settled in a job, didn’t marry, and lived with his parents in Ealing until their deaths in the mid-1960s.

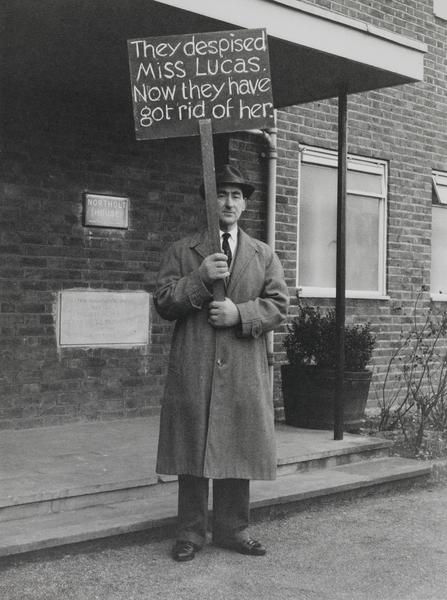

One photo in our collection shows Green before his diet campaign, with a sign saying: “They despised Miss Lucas. Now they have got rid of her”. The sign may relate to an incident in 1967 when Green was banned from visiting an old people's home in Northolt.

Possibly Green's first protest sign.

“Green lived simply, practising what he preached”

Leaflets against lust

After his mother’s death in 1967, Green began his campaign blaming protein for what he felt were dangerous sexual habits and disorder.

Green lived simply, practising what he preached by limiting his protein intake to one egg a day and a mix of milk powder and barley.

Until he was old enough to get a free travel pass, Green cycled 19km to central London almost every day to spread his message.

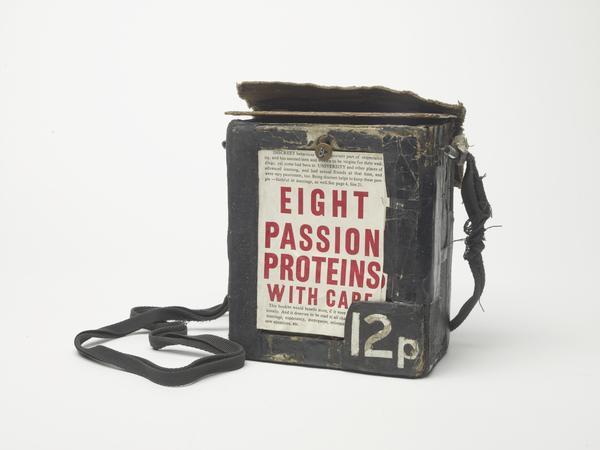

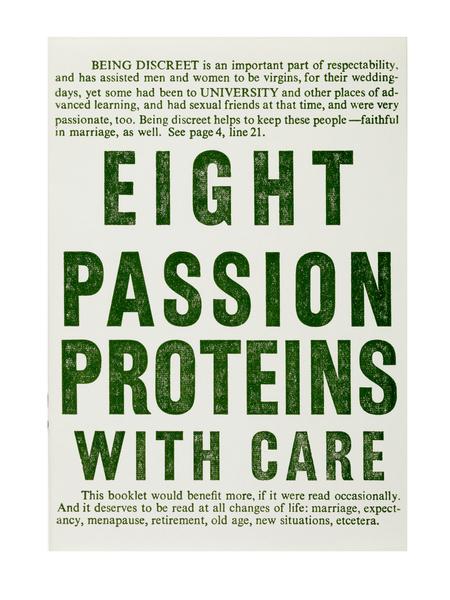

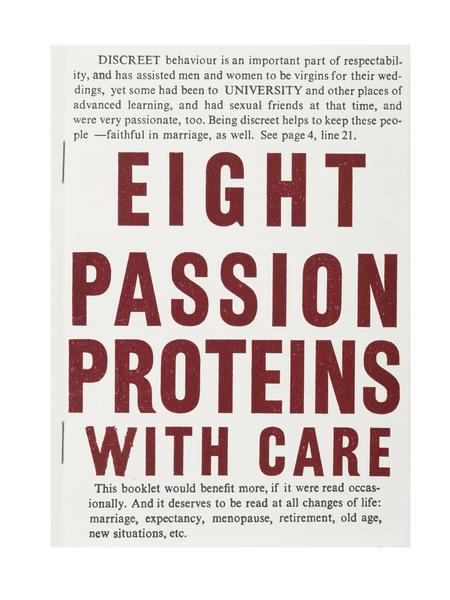

As he walked, he carried a homemade sign and sold his booklets, titled Eight Passion Proteins. With Care. Green claimed to have sold 87,000 booklets in total.

Green printed dozens of versions of his booklets, many by himself in his front room. Each version contained an ever-more jumbled message about biological rhythms and sexual restraint.

At times it criticised the sexual habits of students and warned about the effects of school sex education.

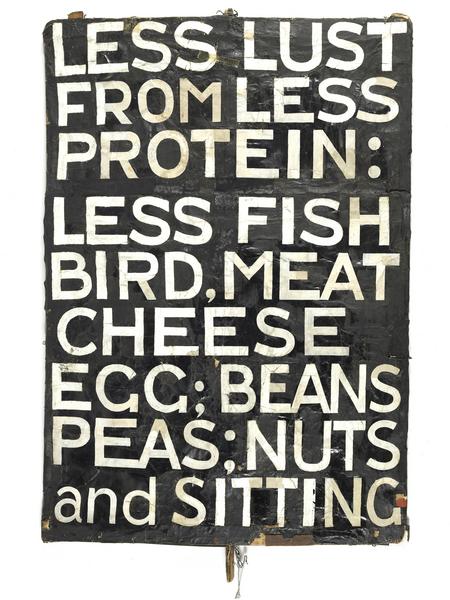

Green’s sign

Green called his sign “the most important part of my dedicated work”. The message was simple, if puzzling: Fish – bad. Meat – bad. Bird? – bad.

It changed as new theories came to mind: the addition of “and sitting” reflected his belief that exercise stopped protein building up in the body.

“Dear Mr Green... my rhythm appears unchanged”

The letter campaign

In the evenings, Green wrote letters to public figures.

He often wrote to Margaret Thatcher, who he believed had secretly started to practise his philosophy of “Protein Wisdom”.

“Protein Wisdom would not reduce your circulation and it might increase it!”, he told the editor of The Times. Referring to the government’s campaign to raise awareness of AIDS, he asked Prime Minister John Major: “will your government be yet another that will promote sexual promiscuity among young people?”

People also wrote to him. “Dear Mr Green,” wrote one, “I read your interesting pamphlet tonight and whilst I find it most intriguing, I must confess that some of the points raised do need some clarification... I experimented with your methods for a period of time last month – my rhythm appears unchanged.”

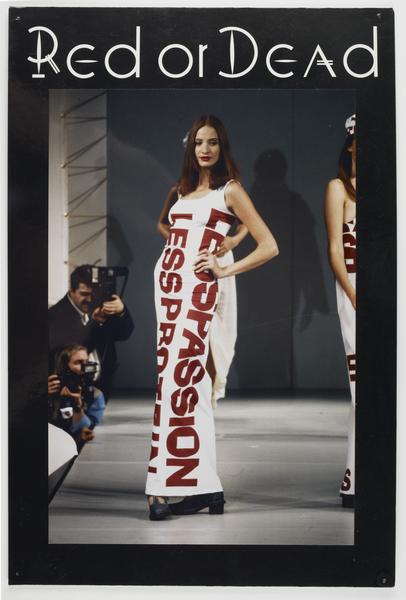

A 1998 range of clothing by Red or Dead used Green's Less Passion, Less Protein campaign as inspiration.

International fame

Protein Man’s reputation and print style won him commercial attention too.

In 1988, the advertising agency Bartle Bogle Hegarty used him to promote the Campaign Poster Advertising Awards. The fashion brand Red or Dead also used his message on a dress design.

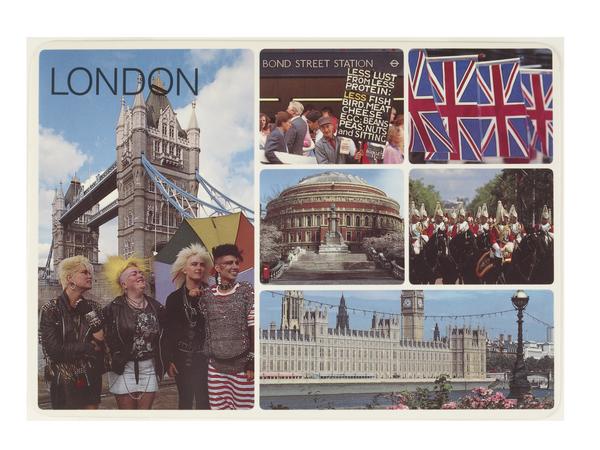

Green appeared on countless international television programmes as an example of British eccentricity. He pops up on a postcard in our collection too, labelled simply as “Oxford Street Character”.