Silvertown 1917: London’s largest explosion

On 19 January 1917 a fire at a docklands TNT refinery in Silvertown, east London caused London’s largest ever explosion, killing 73 people.

Silvertown, east London

1917

A wartime tragedy far from the battlefield

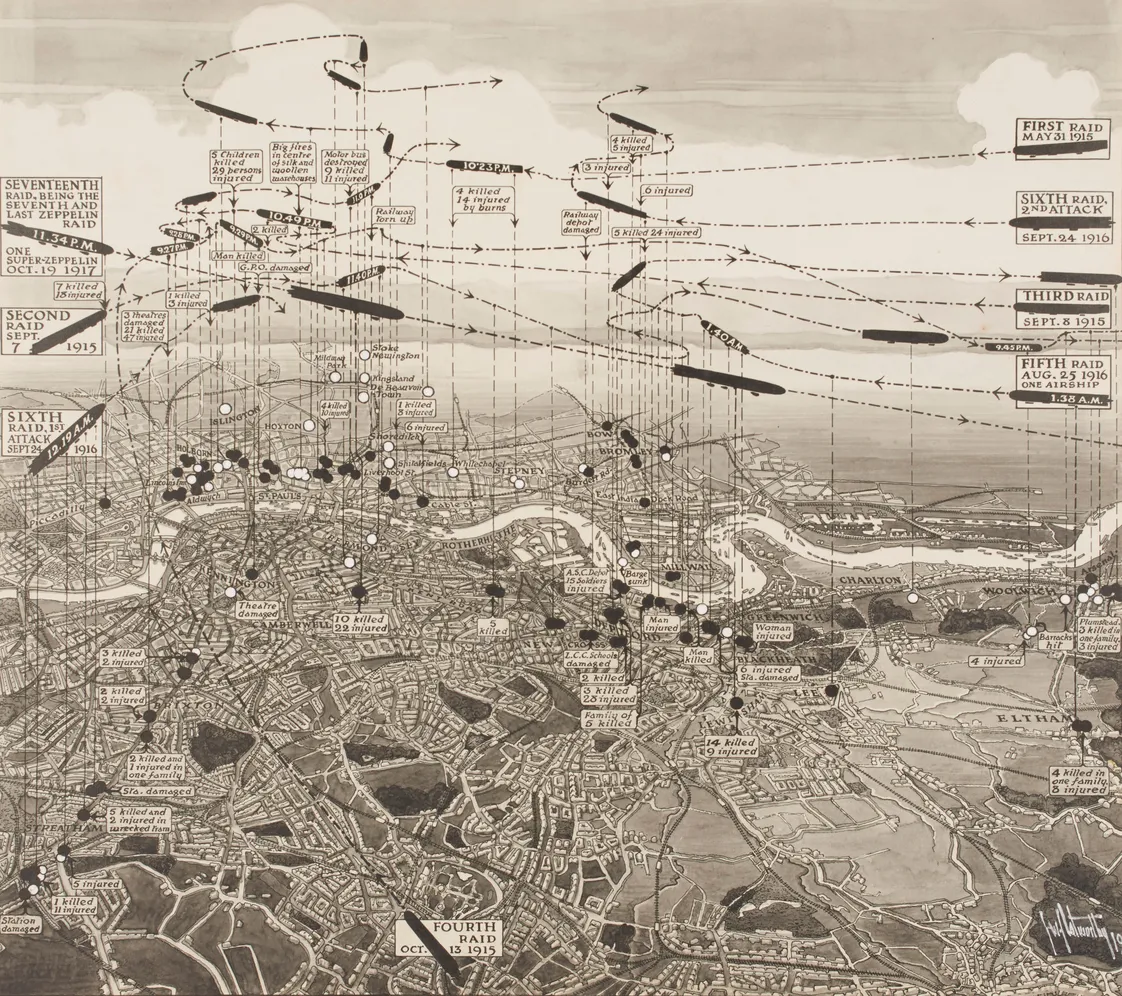

The Silvertown explosion came while Britain was fighting the First World War, and many jumped to blame their enemy. London had already been attacked by air, with German zeppelins dropping bombs between 1915 and 1917.

The truth was harder to take – this was a tragic and preventable accident.

How did it happen?

Just before 7pm on 19 January 1917, a fire started at Brunner Mond & Co, a factory refining TNT for use in the First World War (1914–1918). The fire caused 50 tonnes of high explosives to detonate.

What were the effects?

A large part of the factory was instantly destroyed, together with nearby grain stores and 900 local homes. A total of 60,000–70,000 buildings were damaged, as flaming debris caused fires for miles around.

73 people died and over 400 were injured – including many children. Tug boats at the docks ferried injured people to hospital.

Fires could be seen as far away as Guildford. Shockwaves were reported in Norfolk and Southampton. And despite the efforts of over 100 firefighters, fires continued to burn for more than a week afterwards.

“the report wasn’t made public, fuelling speculation that this had been a German attack”

How did the area recover?

The day after the explosion, local authorities set up the Explosion Emergency Committee to oversee rescue and rebuilding work.

Other docks were quickly assigned to receive and transport grain, which was especially important to Britain during wartime.

By mid-February 1917, more than 1,700 men were working to repair houses. By August most of the work was complete, although the Royal Victoria Dock wasn’t fully repaired until the 1920s.

Why were explosives being made in Silvertown?

Silvertown sits on the River Thames, south of the Royal Victoria Dock. It developed into an industrial area in the 1850s and was named after Samuel Winkworth Silver, who established a factory there.

Silvertown was beyond the part of London governed by the 1843 Metropolitan Building Act, which controlled dangerous industries. Hazardous materials, including caustic soda, sulphuric acid and petrol, were all handled there.

During the First World War, the government desperately needed explosives. In 1915, Brunner, Mond & Co’s chemical plant was ordered to begin producing trinitrotoluene – better known as TNT.

The company resisted. Although Silvertown was an industrial area, it was densely populated by workers living in rows of terrace houses.

But the pressures of the First World War overrode the concerns.

What the inquiry found

An inquiry judged that Silvertown had been a totally unsuitable place for an explosives factory. The report scolded Brunner, Mond & Co for negligence too.

But the report wasn’t made public, fuelling speculation that this had been a German attack, not an accident.

The government eventually paid about £3 million in compensation to the people affected by the Silvertown disaster. The Port of London Authority (PLA), which ran the Royal Victoria Dock next to the factory, claimed the most.

It wasn’t until the 1950s that the inquiry report was released.

The Silvertown explosion wasn’t the only disaster of this type during the First World War. An explosion in 1918 at the Chilwell ammunition factory in Nottinghamshire killed 134 workers and injured 250.

Photographing the destruction

The impact of the explosion on Royal Victoria Dock is made significantly more real thanks to the photos of John H Avery, which are part of the PLA Archive at London Museum.

These photos are unique, as public and press access to Silvertown and the docks was limited at the time. The Port of London Authority commissioned Avery to capture a record of the damage to their property for the compensation claim they made to the government.

His photos from several days after the explosion show twisted metal, fires still burning and the desolate scene it left behind.

Research credit: Vyki Sparkes, Curator (Social & Working History)