The story of Samuel Pepys’ silver plate

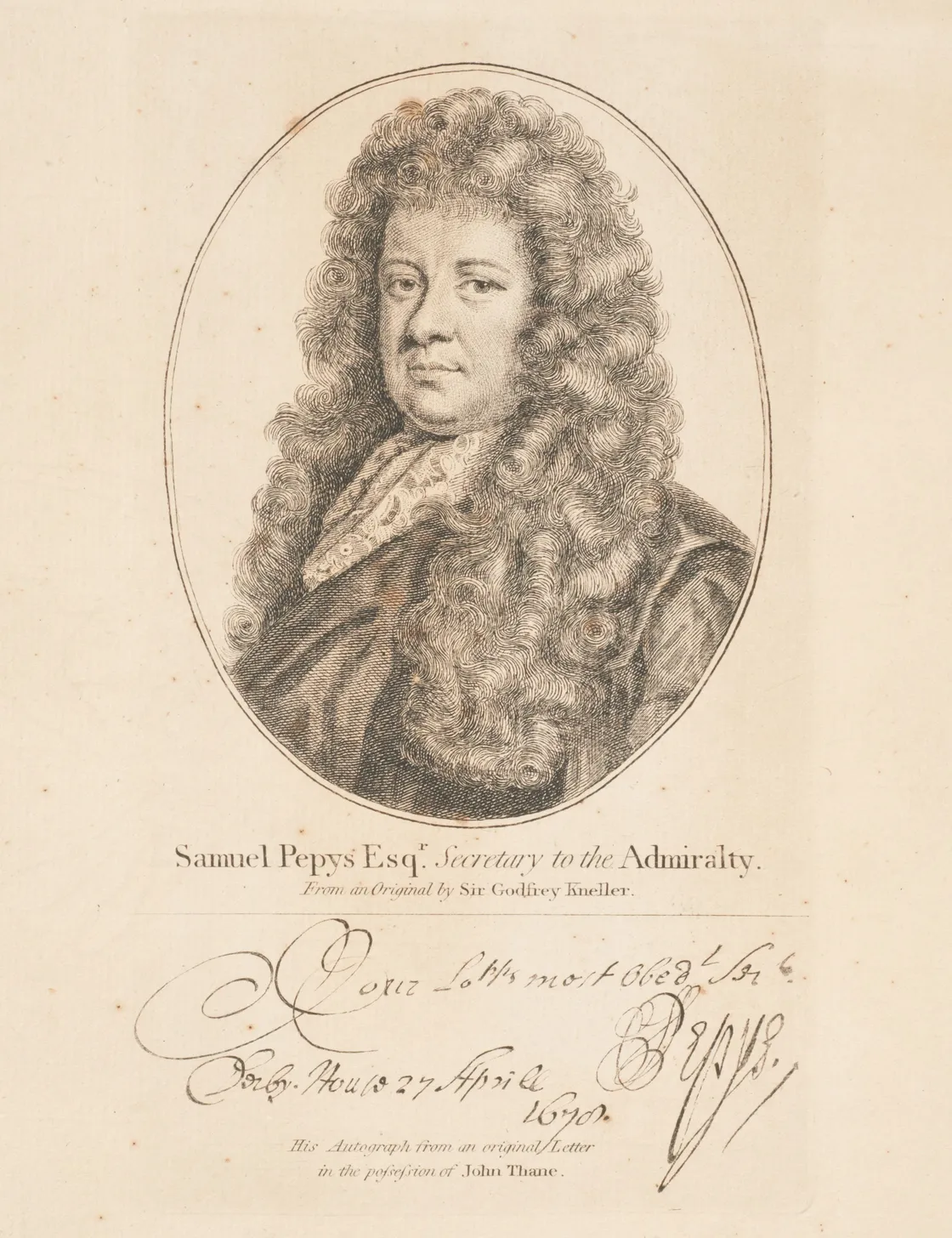

Samuel Pepys is most famous today for his diary, which recorded life in 17th-century London. This extremely rare silver plate, owned by Pepys, can tell us more about the man and his times.

1633–1703

Dining on success

For part of his life, Pepys was careful and concerned about money. But his career as a navy official eventually made him rich.

Like many in the 17th century, he invested his money in silver objects – an important display of wealth which he enjoyed showing off to his friends.

Pepys’ diary is a fascinating, detailed record of 17th-century London. But this plate makes it even more real, representing concerns we’d all recognise – money, career and owning beautiful things.

What can we see on the plate?

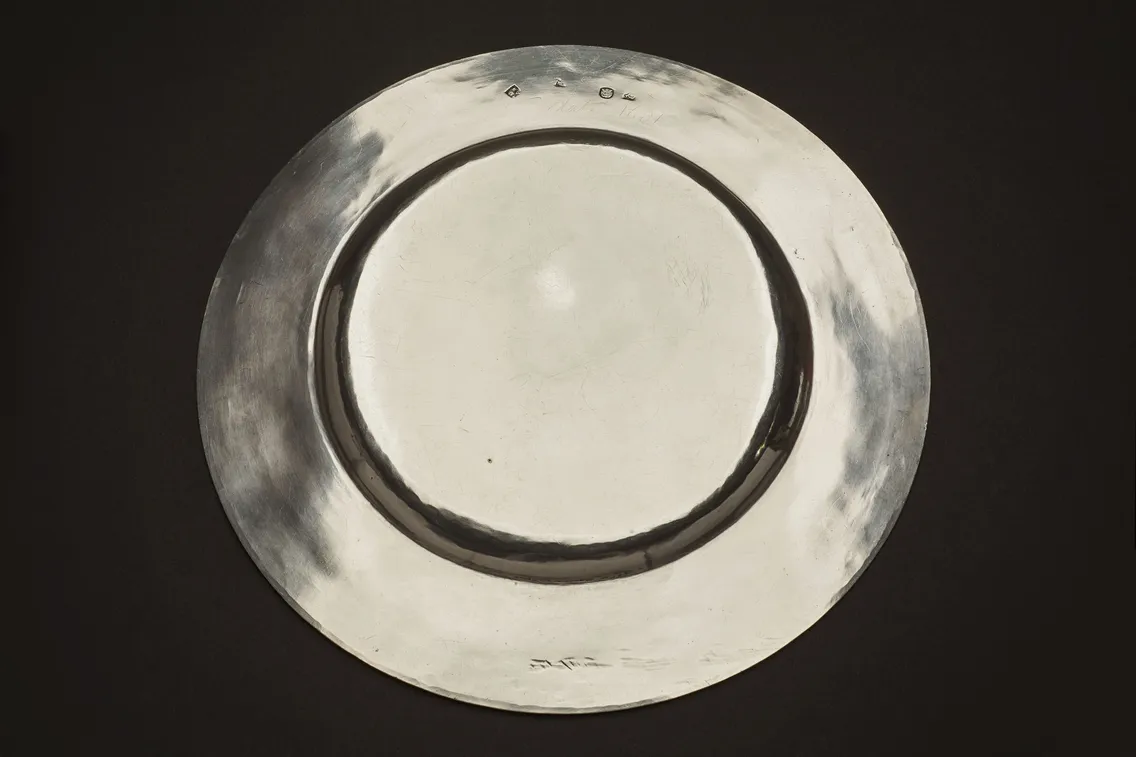

This plate has visible scratch marks on it from knives and forks, proving that it wasn’t just for show.

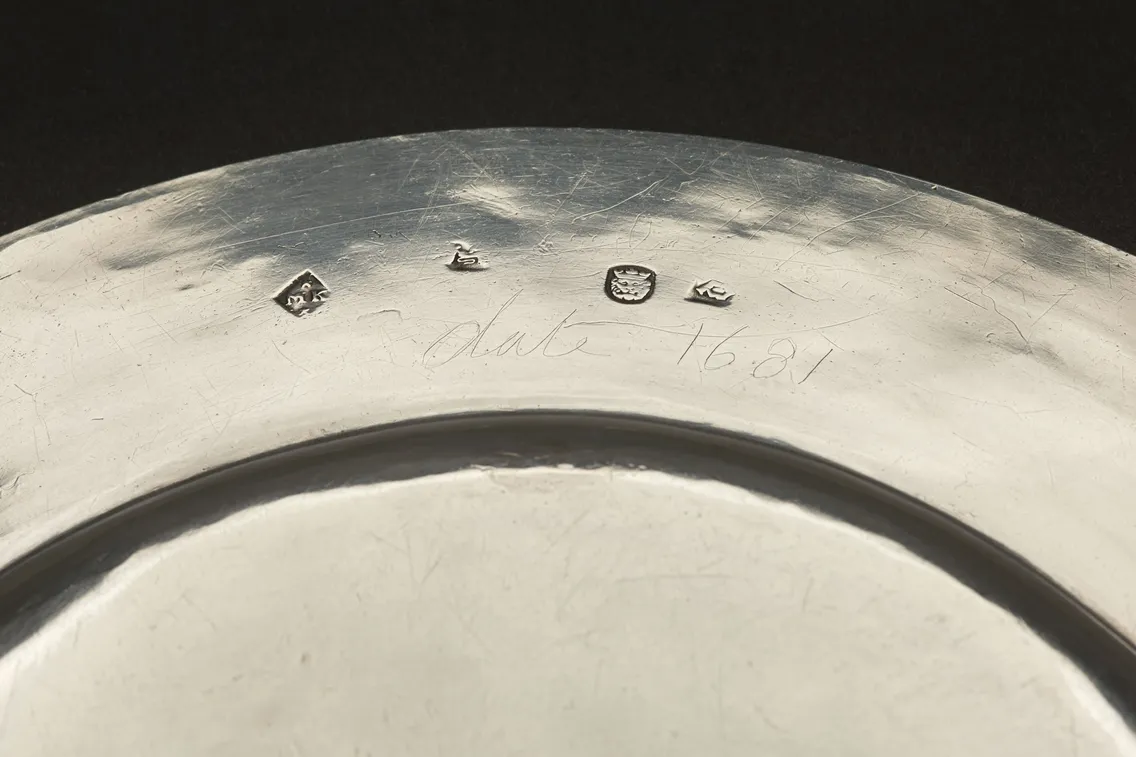

The rim is engraved with the coat of arms of the Pepys family. The underside has London hallmarks – symbols stamped into the silver which guarantee the purity of the metal.

Another mark, known as a date letter, tells us it was made between 1681–1682. And the maker’s mark shows us it was made in the workshop of Mary King, in Foster Lane, just north of St Paul’s Cathedral in the City of London.

Why is this plate so special?

Very little 17th-century silver has survived. Silver was seen as an investment, and silver goods were constantly reshaped or melted down.

This plate is one of just three surviving items of silver known to have belonged to Pepys. The other two are now in the USA.

So it’s very special that this object, which belonged to one of the most famous Londoners, is in our collection, in the heart of London, so close to where it was made.

Pepys is most famous for the diary he kept, but he made his money as a naval administrator.

Who was Samuel Pepys?

Samuel Pepys was born in Salisbury Court, just off Fleet Street, on 23 February 1633.

After graduating from Magdalene College, Cambridge, Pepys worked for his influential cousin, Edward Montagu the Earl of Sandwich.

With his cousin’s backing, in 1660 Pepys became Clerk of the Acts for the Navy Board, helping it organise the building and repair of ships and the management of the dockyards.

In the same year, King Charles II was restored to the throne, and on New Year’s Day, Pepys started to write a diary. He continued for nine years, until fear of blindness caused him to abandon it.

His diary includes a record of two major historical events – the 1665 Great Plague and the 1666 Great Fire – as well as everyday London life 500 years ago. When it was published many years after his death, the diary made Pepys one of London’s best-known writers.

How rich was Pepys?

When Pepys assessed his personal wealth at the beginning of his diary, he had an estate worth just £25. He was “troubled with thoughts [about] how to get money” to pay off his debts. But he acknowledged he was far from poor: “My own private condition [is] very handsome.”

Since every penny counted, he made a point of keeping just three pence in his pocket while out drinking with friends, to prevent him spending more.

His Navy Board job gave him a salary of £350. But still Pepys was spending more than he earned. He was desperate to find more income, “or else I may resolve to die a beggar.”

He did much better than that. During his diary-writing period, Pepys was very successful in his career. He was soon rich enough to live in style and collect books, prints, silver, household furnishings, ship models and “curiosities”.

Pepys’ finances were improved through bribes and gifts given to him in return for contracts he handed out in his navy job.

By the time he stopped writing his diary, Pepys was rich. He had a salary of over £500, a “mighty handsome” home, a painted and gilded coach, and £10,000 in savings.

“Lord, to see with what envy they looked upon all my fine plate was pleasant”

Samuel Pepys, 1667

Why did he buy silver?

In the 17th century your wealth wasn’t demonstrated by the size of your house. It was furniture and silverware which mattered.

Pepys gradually began to buy silver items. Some of it he paid for himself, but more often it came from work-related gifts.

In July 1664, he received a pair of silver-gilt flagons, a type of drink container. These were soon displayed to the envy of Pepys’ dinner guests, with a dozen silver salt containers, besides his “great cupboard of plate”.

Having so much silver was an opportunity to show off. On 8 April 1667, Pepys wrote: “we had, with my wife and I, twelve at table… and a most neat and excellent, but dear dinner; but Lord, to see with what envy they looked upon all my fine plate was pleasant, for I made the best show I could, to let them understand me and my condition, to take down the pride of Mrs Clerke, who thinks herself very great.”