Relics of King Charles I’s execution

The public execution of Charles I was a seismic historical event. Clothes in our collection are said to have been worn by the king on that day – personal objects which transport us to his final moments.

Banqueting House, Whitehall

30 January 1649

Are these the relics of a king’s last day?

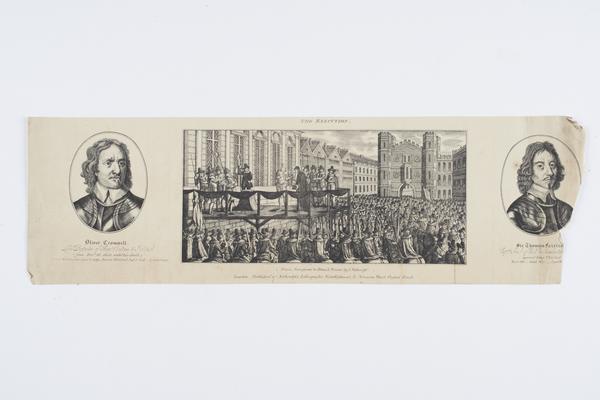

On 30 January 1649, Charles I was executed on Parliament’s orders for “High Treason and other high Crymes”.

In one of British history’s most dramatic events, he was beheaded in front of a huge crowd on a stage at Whitehall.

We know about it from written descriptions. There are drawings and paintings which claim to show what happened. But, in London Museum’s collection, we may have something from the moment of the event – a vest, fragments of a cloak and other items which people have claimed he wore on the day of his execution.

We can’t know for certain if these objects really belonged to Charles – but their history is a mystery worth investigating.

Why was King Charles executed?

In 1642, Charles I’s failed attempt to arrest five MPs for treason led to angry protests in London. The king fled the capital and the country plunged into civil war, with royalist armies battling Parliament’s forces for power.

After being taken prisoner, Charles continued to plot to regain the throne. Parliament tried the king for treason and sentenced him “to be put to death by the severing of his head from his body”.

How was Charles I executed?

Charles was beheaded on 30 January 1649 in front of the Banqueting House in Whitehall. A crowd of men and women came to watch the extraordinary event.

Choosing the luxurious Banqueting House was symbolic. It represented the extravagance of Charles I – and his belief that kings rule because God has chosen them.

An eyewitness claimed that, as Charles was beheaded, “there was such a groan by the thousands then present as I never heard before and desire I may never hear again”.

“Let me have a shirt on more than ordinary”

Charles I, quoted by Thomas Herbert, 1678

Charles’ execution outfit

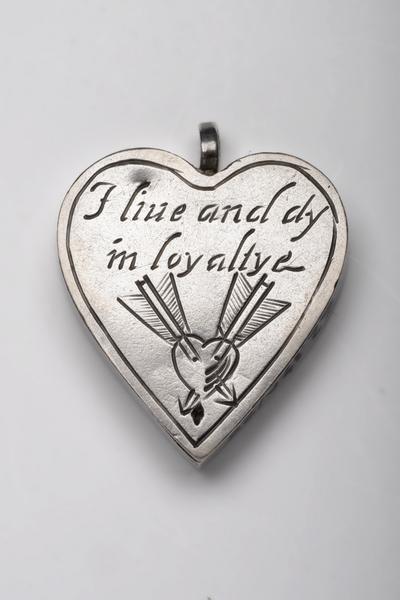

Objects linked to the king were prized after his death. Spectators dipped their handkerchiefs in the king’s blood.

Our collection includes pendants and badges made to mourn his death. But the objects we have which were apparently worn by Charles I at his execution are potentially even more special.

The material and style of these items suggest they’re from the correct date. They are also of the right quality to have been owned by a king.

But we can’t be sure. There are different descriptions of what the king wore and who took the items after his death.

The king’s extra vest

Thomas Herbert was the king’s attendant during his last two years. In his 1678 memoir, Herbert describes how, on the morning of his execution, Charles “appointed what clothes he would wear; ‘Let me have a shirt on more than ordinary,’ said the king, ‘by reason the season is so sharp as probably may make me shake, which some observers will imagine proceeds from fear… I fear not death!’”

In other words, the king didn’t want the crowd to think he was shivering in fear – so he asked for an extra layer to keep him warm.

London Museum acquired a blue vest in 1924, along with a note claiming it had been worn by Charles I at his execution.

The note says that the vest “from the scaffold came into the hands of doctor Hobbs, his physician who attended him upon that occasion”. The family of this doctor kept the vest until the late 19th century, when it was sold and resold several times.

According to recent research, there are at least two linen shirts and a satin jacket that have been linked to the king’s execution. However, none has been proven to be genuine.

The king’s gloves, handkerchief and cloak

We also have several pairs of gloves, fragments of a cloak, a handkerchief and a silk sash – all allegedly given to loyal friends or followers in Charles’ final days.

The black cloak is thought to have been given to Charles’ attendant, Sir Thomas Herbert, before the king passed from Banqueting House onto the scaffold outside. One of Herbert’s daughters allegedly gave the cloak to Countess Johanna Sophia of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, who was based at the English royal court in the early 18th century.

The fine leather gloves with silver embroidery are said to have been given to Bishop William Juxon, who accompanied the king to his execution.

Several pairs of gloves are claimed to have the same origin. Embellished gloves were popular gifts. The accounts of Charles I list more than a thousand pairs of gloves – suggesting he often presented them to others.

Unlike the other relics, the fine linen handkerchief in our collection is unusually plain for a king. However, it is embroidered with the king’s initials, “CR”, in red silk. It is said to have been carried by Charles I on the day of his execution.

The sash – made from silk and metal thread – is also linked to Charles I. Decorated with silver-gilt lace and spangles, the sash would have been a very expensive, high-status item, worn across the body or around the waist, over a jacket or coat.

This article contains edited excerpts from Executions: 700 years of public executions in London, written by Thomas Ardill, Meriel Jeater, Beverley Cook and edited by Jackie Keily.