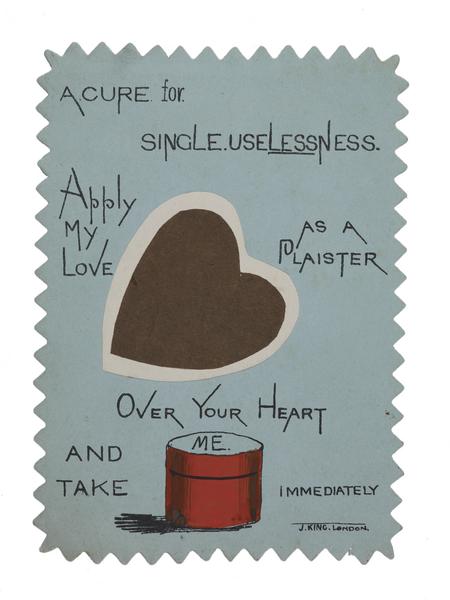

Quirky Victorian Valentine’s Day cards

Valentine's Day cards were big business in Victorian London, and stationers competed to be the most unique and eye-catching handmade designs. See some of the weird and wonderful highlights in our collection.

Islington

1800s

They don’t make them like they used to

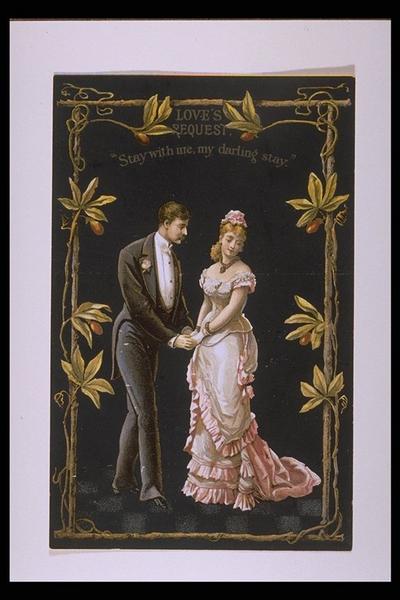

Loved-up lobsters. Roller-skating cupids. Uncomplimentary caricatures. Back in the 1800s, you had some pretty unusual options for sending little notes to the person you loved (or loathed).

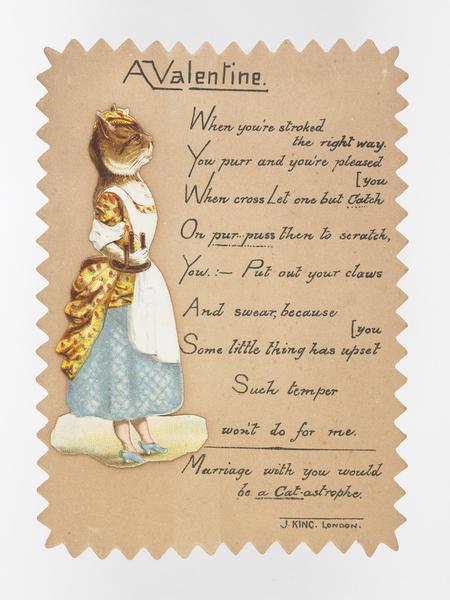

London Museum has over 1,700 Valentine’s Day cards in the collection – all designed and printed right here in London. Most were made by one Islington based stationer, Jonathan King, who ran a card making studio on Essex Road with his wife, Emily. Their daughter Ellen supervised the workroom. The unique cards were either sold in their shop next door, named the Fancy Valentine Shop, or by travelling salesmen.

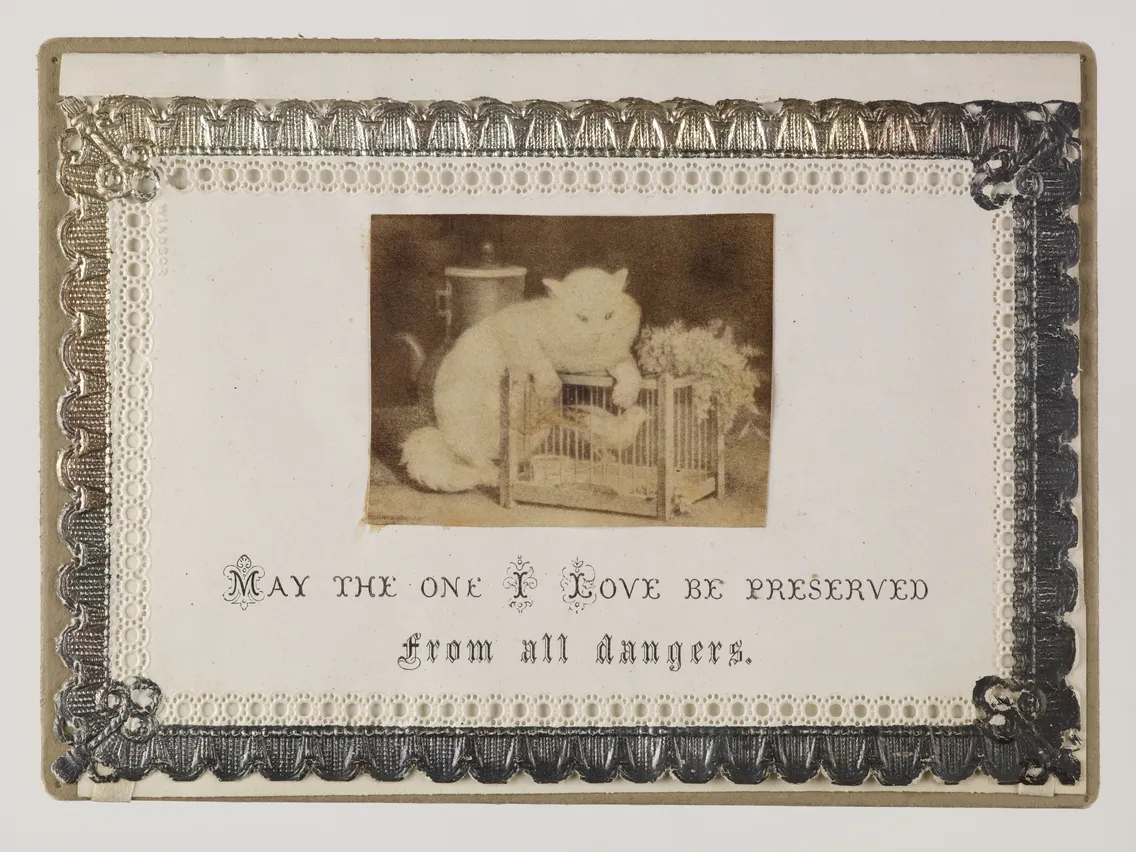

As well as the beautifully illustrated and romantic, the cards in our collection range from gentle teasing and novelty to downright insulting and plain weird. Some just remind us that amusing cat pictures have never really gone out of style.

When did Londoners first send Valentine’s Day cards?

London’s relationship with Valentine's Day cards goes back at least two hundred years. By the mid 1820s, an estimated 200,000 valentines circulated annually within London.

In 1840, the Post Office introduced a new service where letters could be sent across the country for one penny using the first postage stamp, known as the Penny Black. The number of Valentine’s Day cards sent then skyrocketed. By the late 1840s the number was reported to have doubled, and had doubled again by the 1860s.

Sending cards through the penny post meant you could maintain the playful aspects of formal courtship. But you could do so anonymously, or provide clues to your identity.

Stationers cash in on the romance

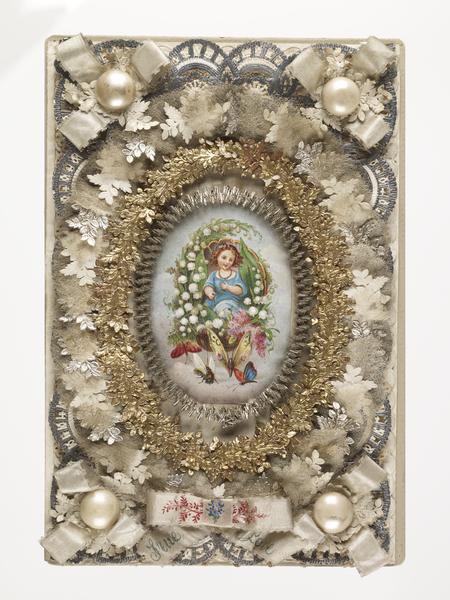

At this time of year, London stationers like King put on enormous, impressive displays of Valentine's cards in their shop windows. They experimented with thousands of ideas for cards sold throughout the country. Many of these are elaborately hand-made. Paper scraps were collaged with hand-painted illustration and lace paper, some of which are several centimetres deep.

“Some cards went as far as integrating stuffed birds into their collages”

By the mid-19th century some valentine traditions had already been established and card makers adapted these into their designs. Springtime rebirth, flowers and rhymes were already popular Valentine's Day motifs, and the sentimental Victorian image of cupid was not far behind.

Birds were also such a favourite motif that some cards went as far as integrating stuffed birds into their collages, like the unfortunate canary on this card.

Tissue paper flowers, dried grasses – and a stuffed canary bird.

Many of these cards also contain proposals of marriage, or sometimes references to pre-existing engagements. It's a reminder of the formality of courtship for many Victorian Londoners.

But the relentless search for novelty also led to some really unusual designs.

Niche and novelty valentines

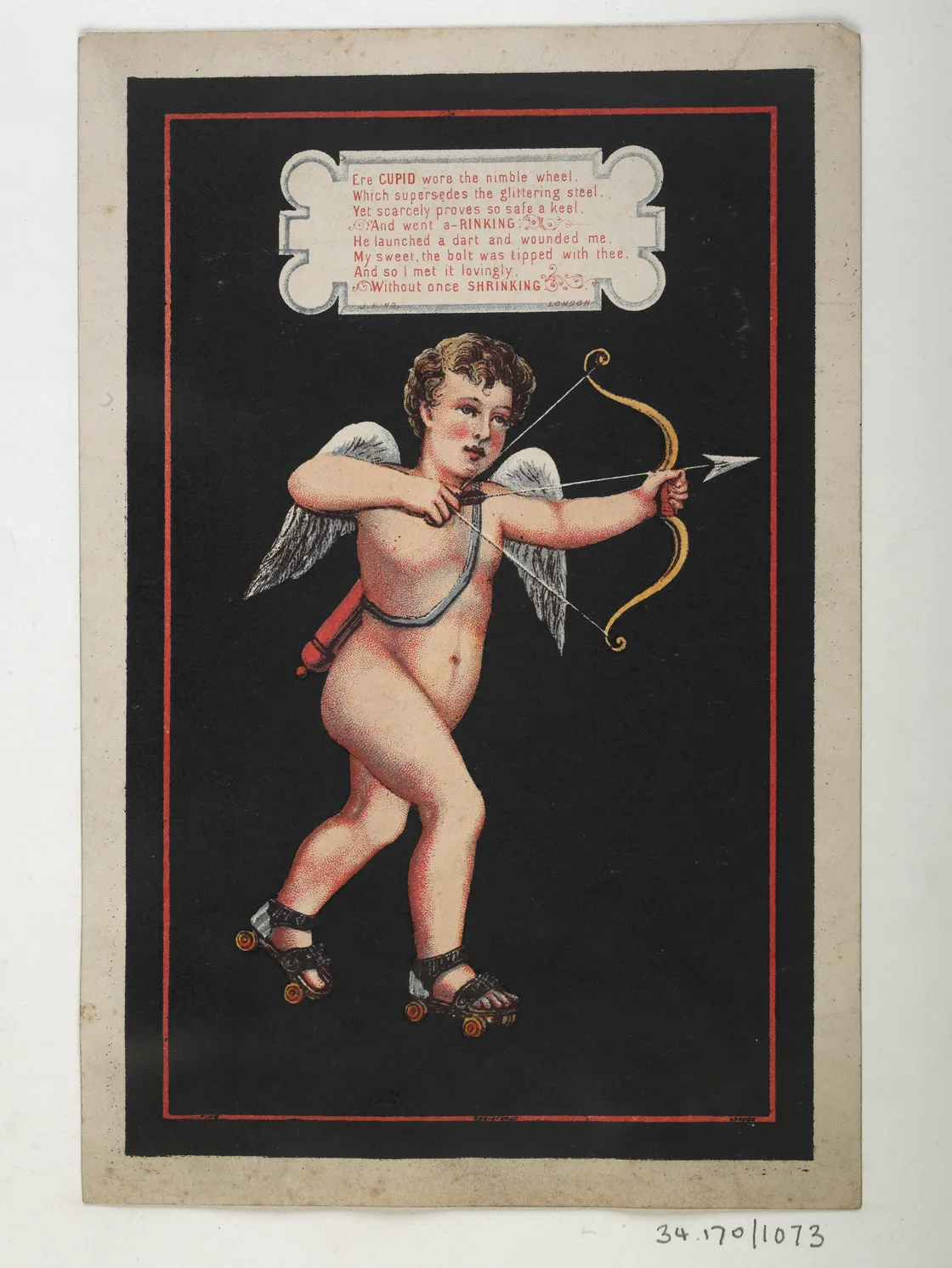

This card features a roller-skating cupid. By the late 19th century, when it was made, roller skating was a big craze in London and rinks opened across the city, bringing a new opportunity for people to socialise. Perhaps this card was designed to be bought by those skated head-over-heels in love.

The message reads: "Ere CUPID wore the nimble wheel, Which supersedes the glittering steel, Yet scarcely proves so safe a keel, And went a-RINKING He launched a dart and wounded me, My sweet, the bolt was tipped with thee, And so I met it lovingly, Without once SHRINKING."

Roller-skating cupid.

Weird and alternative valentines

Could you be a “lobster in love”? Novelty cards like this lobster design were produced in the mid-19th century, by which time the common symbols of Valentine's Day were quickly becoming established. But there was still space for innovation. These would have been an alternative and experimental range of cards.

On this lift-the-flap card, the lobster is raised to reveal the message “I have a lady in my head”. This might be a reference to the shape of the meat inside a cooked lobster, which supposedly could be said to be shaped like a woman.

In our collection, we have samples of all the cards produced in King’s Islington workshop. Workers were allowed to create their own designs – but the Kings had the final say on what was good enough to sell. Their notes on the scrapbooks of sample cards showed not all designs met their taste.

"A boot-iful valentine".

As the cards were collected from shop stock, we don’t know quite how many of these were sold. Sadly, the lobster experiment did not take off and failed to last through the years as a romantic motif.

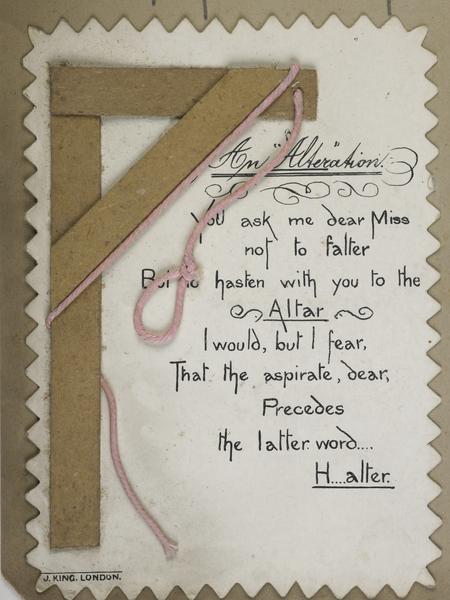

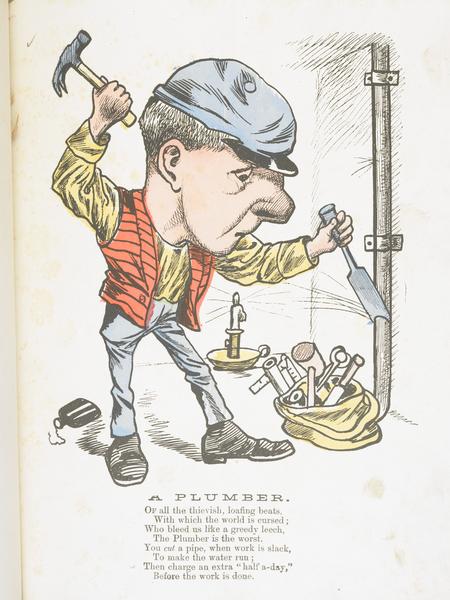

He loves me not? Mean and insulting valentines

The entrepreneurial spirit of these early card makers merchants evidently identified a gap in the market. Why limit Valentine's Day purchases to your one and only sweetheart when you could send cards to all the people you disliked as well?

Many stationary shops, including King’s, sold a wide selection of less affectionate valentines made by commercial suppliers. Some had really spiteful messages. Unlike the ornate sentimental cards, the insulting cards certainly weren’t made of expensive, embossed lace papers. They were mostly cheaply printed and crudely hand-coloured. They're clearly disposable, meant to be dashed off as anonymous jokes.

As well as a caricature, they include mocking rhymes that explain why the recipient can never hope for romantic feelings from the sender. For example, many of these have images of tradespeople that show the stereotypical or discriminatory views commonly held at the time. Others also had highly offensive, racist and anti-semitic visual representations and verses.

The moon, "the only man, who smiles on you!"

There are also some designed to be sent to women. These tend to mock the recipient’s appearance or behaviour. The card above, for example, addresses a women with her fists held up: “Square up my lover of gin twist, I care not for thy mutton fist; And never will my heart refine, For such a swaggering Valentine.”

It’s possible that they were sent with flirtatious intent – although it’s hard to imagine any recipient being forgiving enough for that plan to work.