Pleasure gardens: London’s first music venues

Back in the 18th century, Londoners got their live music fix listening to composers and orchestras in the city’s fashionable summer entertainment venues.

Chelsea & Vauxhall

1700s

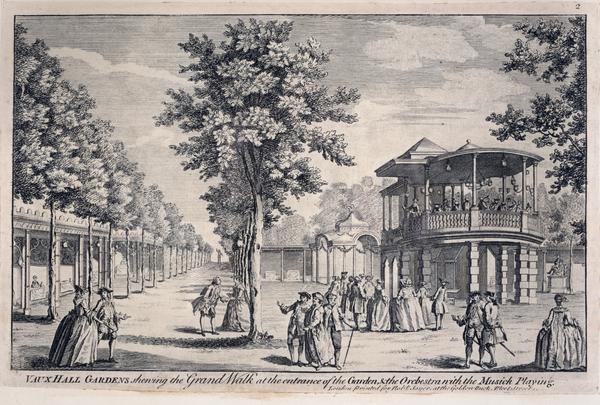

Caricaturists Isaac and George Cruikshank illustrate an evening at Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens.

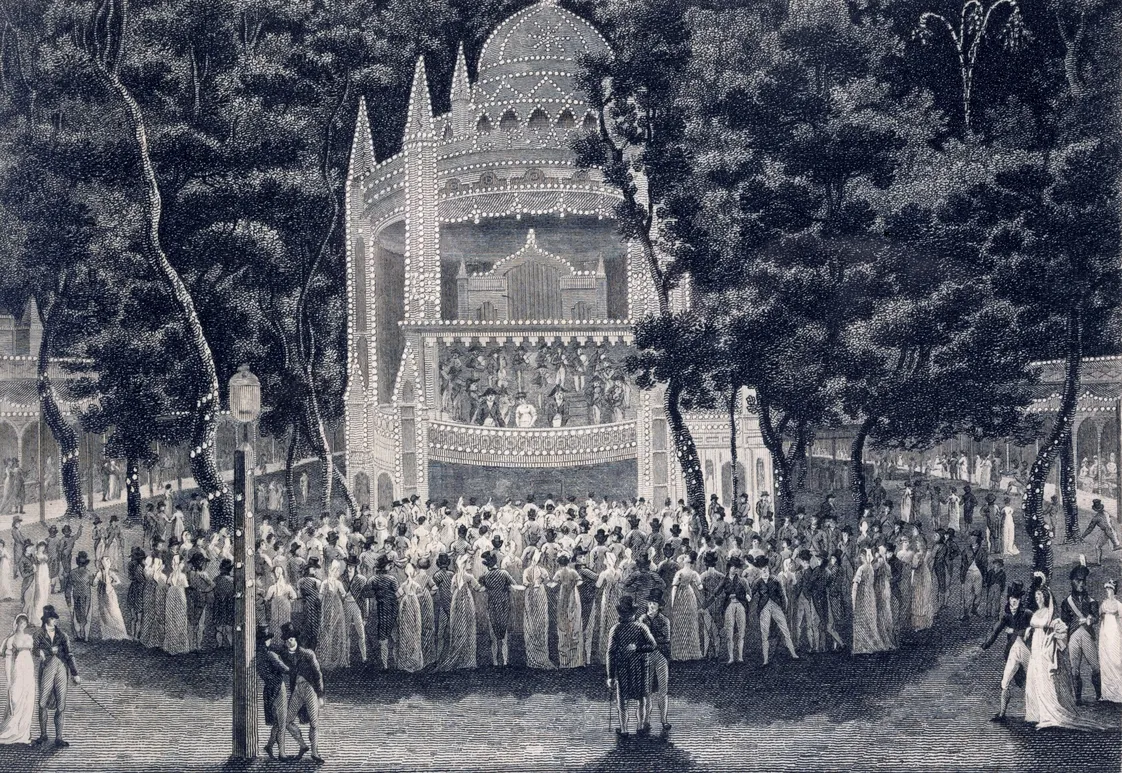

Dancing under the stars

The attractions of London’s pleasure gardens were many. Under glittering nighttime lights, thousands of well-dressed visitors in stylish clothes gathered to socialise, eat, drink and be merry. And the principal entertainment on offer – at least officially – was music.

Music shaped both the architecture and the experience of the gardens. At places like Vauxhall and Ranelagh, you could hear debut pieces from top composers and performers of the day.

Yes, you could go out and hear music across the city – at the Italian opera, or even at the local tavern. But to catch the latest home grown talent? There was nowhere like the pleasure garden.

What kind of music would you hear at pleasure gardens?

Pleasure gardens promoted the latest in English music, and many well-known pieces were first played there. Thomas Arne, who was Vauxhall’s musical director from 1745–1777, was responsible for the patriotic song Rule Britannia, as well as a version of God Save The King.

The music was quite varied. You could hear the likes of concertos, cantatas, ballads, marches, symphonies, dance music and popular songs.

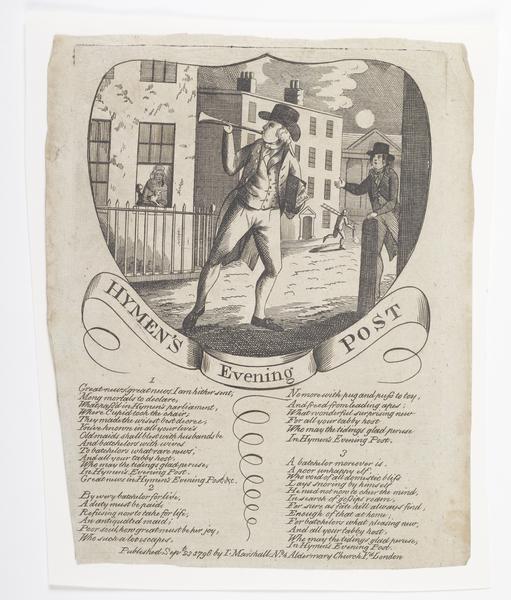

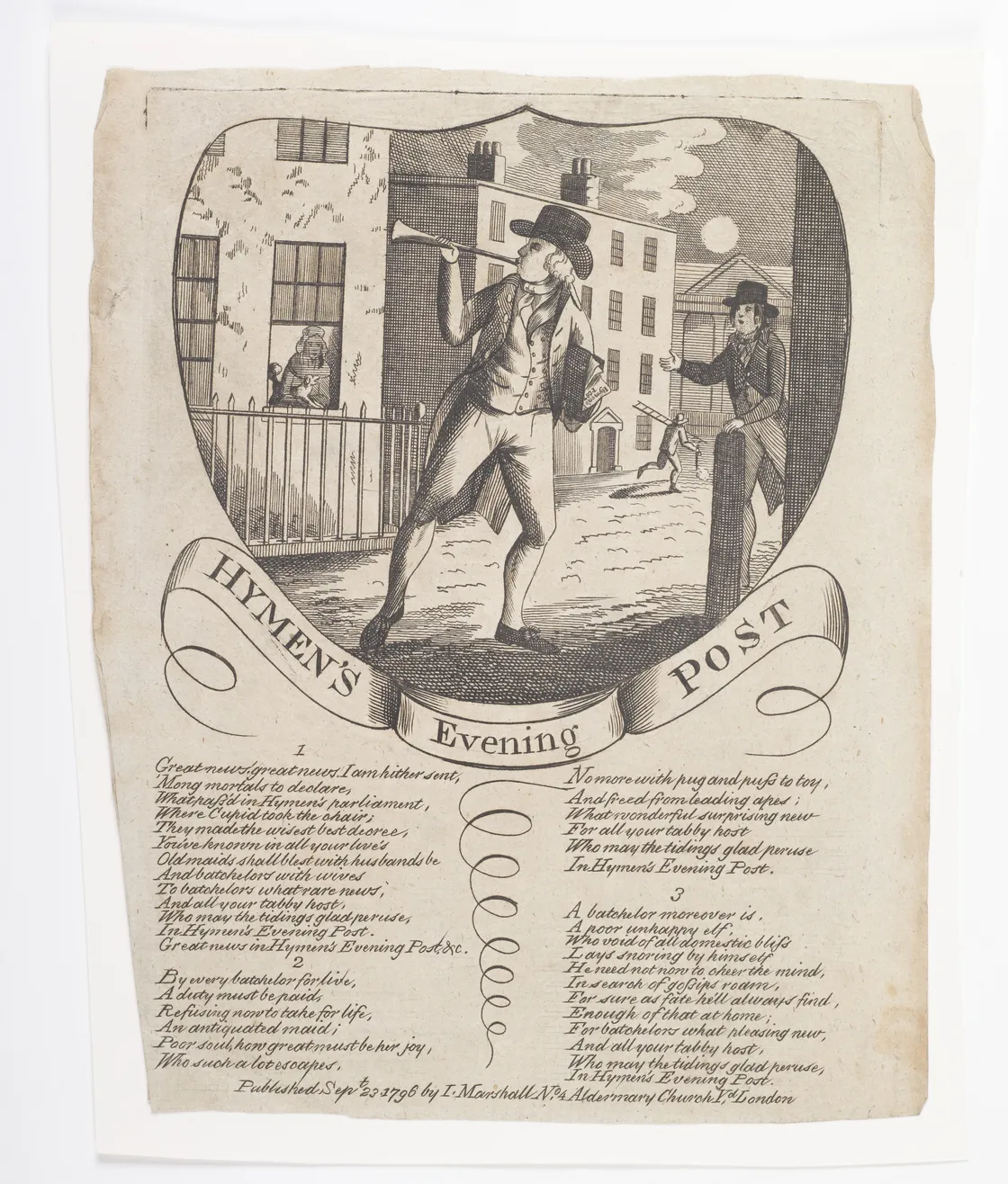

Songsheet of the popular comic song Hymen's Evening Post, which was popularised by regular Vauxhall singer Mr Dignum.

Street sellers also sold illustrated songsheets of popular songs sung at pleasure gardens, such as this for the popular comic song Hymen’s Evening Post. Songsheets would be bought by those going to the performance so that they could sing along. They were often kept as souvenirs, framed and used to decorate the walls of homes.

Who played at the pleasure gardens?

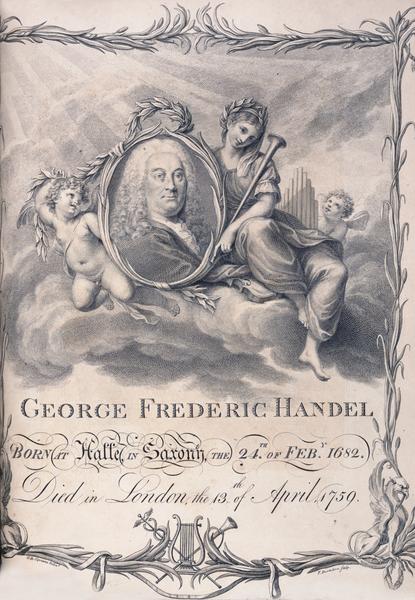

The composer most associated with Vauxhall was George Frideric Handel. He came to England as the Kapellmeister, or master of music, to King George I. Many of his pieces were performed in the gardens during the 1730s and 1740s, including the Vauxhall Hornpipe, written especially for the venue.

When Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks was first rehearsed in the gardens on 21 April 1749, 12,000 Londoners rushed to hear it. This reportedly caused a three hour traffic jam as carriages tried to cross London Bridge – the only bridge within the city – to get there.

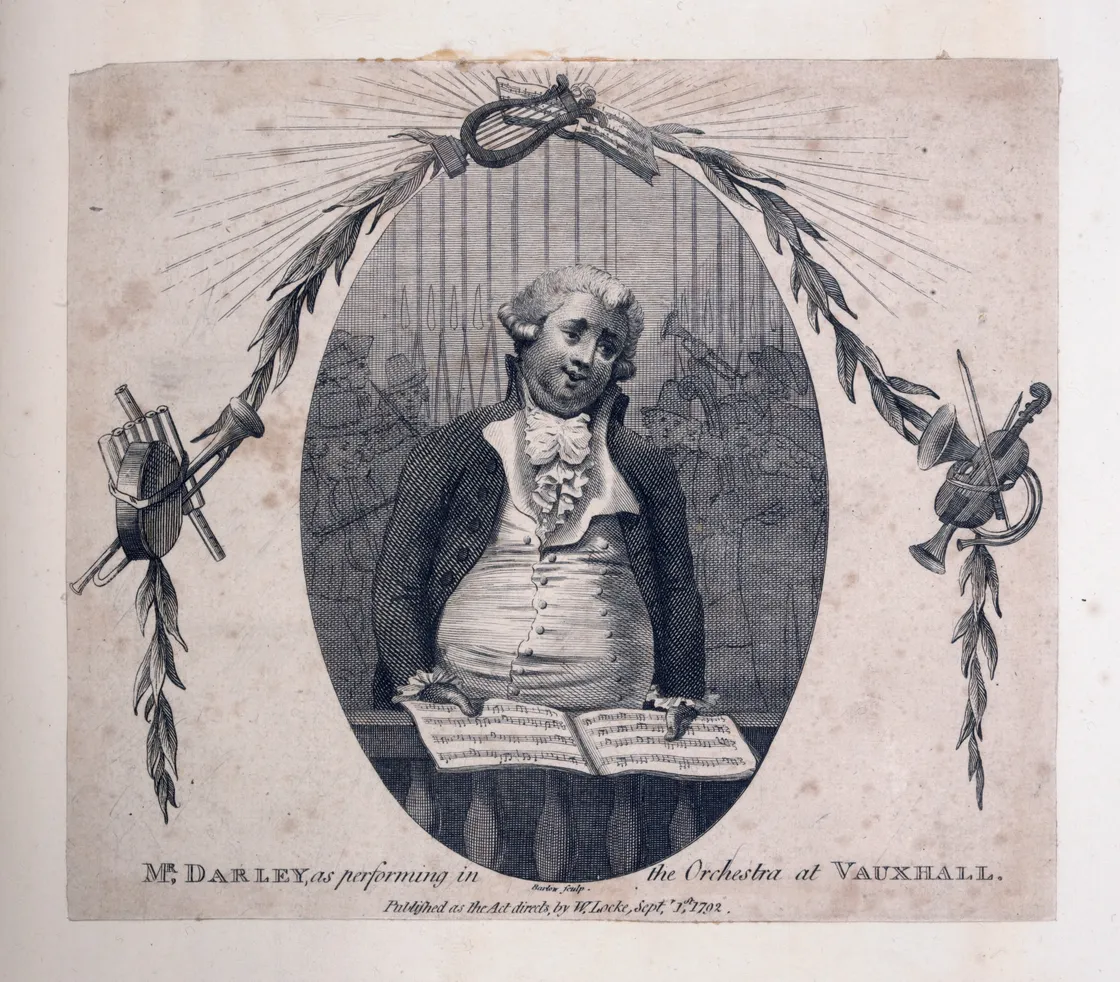

Vauxhall and Ranelagh attracted some of Georgian London's most popular artists.

“the celebrated and astonishing Master Mozart, […] justly esteemed the most extraordinary Prodigy”

1764

Ranelagh also had its share of celebrity musicians. In 1764, the star of a charitable benefit concert was the eight-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who performed his own compositions on the harpsichord and piano. Londoners went wild for his youth and skill. One newspaper described him as “the celebrated and astonishing Master Mozart, […] justly esteemed the most extraordinary Prodigy, and most amazing Genius, that has appeared in any Age.”

Where was the music performed?

Both gardens had dedicated buildings for musical performances. Ranelagh, which opened in 1741, was dominated by a vast rotunda built in the fashionable rococo style. It had a concert space at its centre and private boxes, lounges and gaming rooms around the perimeter.

Vauxhall, its older rival, originally had an outdoor octagonal orchestra stand, with the performers on a high platform so that all could see and hear them. Built in a classical style, it may have been the first structure in Britain purpose-built for musical performance. Not to be outdone by Ranelagh, Vauxhall also built a rotunda for wet-weather concerts, which opened in 1748.

How did the music change over the years?

By the 1790s, the clientele of the pleasure gardens was changing – and so were their demands.

A new manager at Vauxhall introduced a variety of entertainments, such as hot air balloon demonstrations and, after 1816, acrobatics. These were undoubtedly popular, but seen as downmarket novelties rather than high culture.

The music changed accordingly, with precedence given to popular ballads and country dances. Vauxhall and its rival pleasure gardens were still places to hear music but, in the final decades of their existence, no longer the innovative venues they had once been.