Pleasure gardens: London’s early restaurants?

Before the capital had restaurants as we now know them, Londoners first ‘went out’ for a meal in public at places like pleasure gardens.

1700s & 1800s

Drinking and dining under the stars

It turns out trendy, eye-wateringly expensive eating spots are nothing new in London.

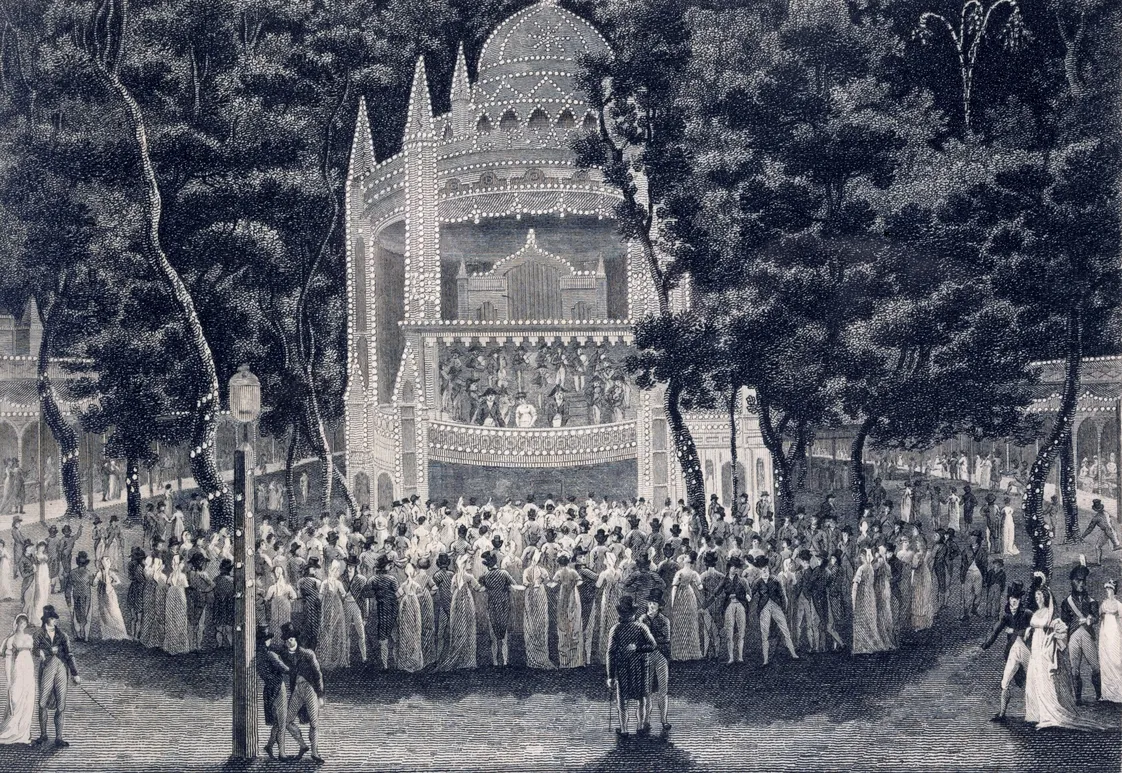

In the 1700s and 1800s, pleasure gardens like Marylebone, Ranelagh and the famous Vauxhall Gardens offered visitors the novel experience of dining out in public. You could refuel with food and drink after whiling away the hours dancing to orchestras, looking at art and socialising among the gardens.

In many cases, the food itself wasn’t great. The portions were small. And it would have cost you a small fortune. But these pleasure garden eateries were some of the early spaces where Londoners dined out in public for fun.

Where did Londoners dine out in the 18th and 19th century?

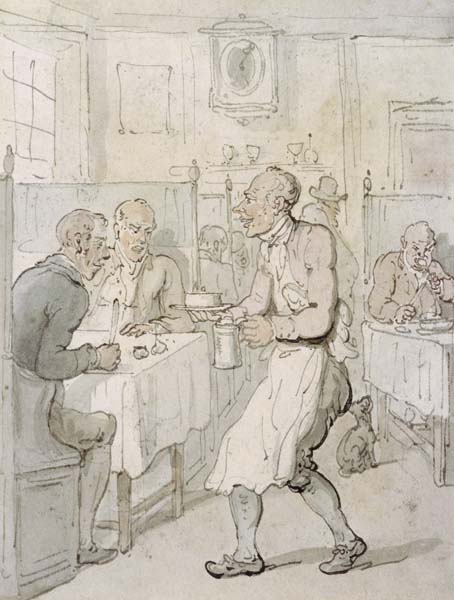

Londoners had a few options of public places to eat. Taverns offered food along with their ales and wines. Chop houses offered cuts of meat, known as ‘chops’, to a typically wealthier clientele. And ‘ordinaries’ served set meals at a fixed price.

Chop houses, like the one depicted in this Thomas Rowlandson watercolour, were common in the City of London.

These places usually provided food for clerks, labourers and travellers passing through the city. Tables were often communal, the clientele was predominantly male, and the food on offer was limited to basic bread and meat dishes. You’d go there out of necessity, rather than for pleasure.

The concept of ‘going out’ for a meal in public didn’t really exist back then. And the modern restaurant, with formal place settings, a menu and a wine list, was a French invention of the 1780s.

What was special about pleasure gardens?

Vauxhall had open-air ‘supper boxes’ in which visitors could order meat, bread, wine and confectionery. These formed a ring around the centre of the garden.

Ranelagh’s grand rotunda had booths for eating and drinking. And Marylebone also offered food to its visitors – including breakfast served with tea, coffee, cream and butter.

For the first time, the wealthy and the prosperous middle classes were eating in the public gaze, rather than the privacy of the home. In the print by Thomas Rowlandson below, you can see notable writers Samuel Johnson, James Boswell, Oliver Goldsmith and Hester Thrale dining in a Vauxhall supper box on the left.

What was the food like?

Pleasure gardens were exciting, glamorous and debaucherous spaces. But the food they offered? It was nothing special.

Just like the music and art you’d find in the gardens, the menu at Vauxhall was consistently English. You wouldn't get elaborate sauces and fancy ingredients of fashionable French cooking here.

Typical dishes included roast chicken, bread and butter, olives and slices of meat so thin you could almost see through them. Vauxhall also served salads that probably included lettuce, cucumber, fresh herbs and the occasional boiled egg, plus a liberal dressing of vinegar and oil.

Fruit-vendors also promenaded in the gardens. These were usually young women carrying baskets of seasonal fresh fruits, such as strawberries and cherries.

How much did it cost?

Eating at Vauxhall was expensive and the portion sizes were small. The price of entry was a relatively affordable one shilling. But in 1762, you’d pay the same shilling for one slice of that see-through ham or beef in a supper box. For context, you could eat a simple but substantial dinner at one of London’s ordinaries for as little as six pence. That’s half the price.

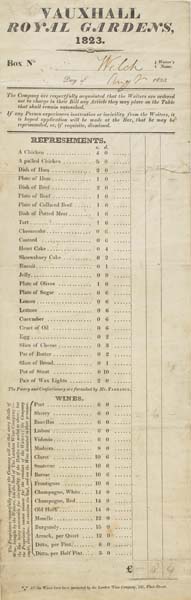

By 1823, you can see from this receipt that the prices had roughly doubled. A chicken would set you back four shillings. A slice of bread cost one pence – the usual price of a small loaf. And if you wanted butter? That’d be an extra two pence, please. The surprise of first-time visitors at these prices, relative to the stingy amounts of food provided, was a running joke among regular patrons.

Yes, food and drink weren’t the most pleasurable aspect of London’s pleasure gardens. But they were still part of the experience – a shared point of reference for Londoners to grumble over, the morning after the night before.

Writing/researching credit: Danielle Thom