Pageantry and protest at Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee

Queen Elizabeth’s Silver Jubilee was celebrated across the nation. Many rejoiced in the parties and pageantry. But others used the Jubilee to protest rising unemployment, poverty and government policy.

Across London

7 June 1977

Street parties and anti-establishment anthems

Elizabeth became queen in 1952, aged just 25. By 1977, she was widely respected as a hardworking monarch. Marking her milestone 25 years as queen, the Silver Jubilee celebrations that summer drew supportive crowds around the world.

But around that time, Britain’s economy was struggling, unemployment was rising and many were living in poverty. People objected to the cost of the jubilee and the monarch when public services were being cut. So the festivities prompted protests from antimonarchists, socialists and punks – including the Sex Pistols.

London Museum’s collection includes a mixture of objects both commemorating and protesting the event.

Queen Elizabeth meets the crowd in Finsbury Park in Harringay.

London’s official Silver Jubilee celebrations

Jubilee Day, the crown jewel of the Silver Jubilee year, took place on 7 June. London was at the centre of the festivities.

A spectacle of royal pageantry took over the city’s streets. Up to one million people lined the processional route from Buckingham Palace to St Paul’s Cathedral, which the queen travelled down in the Gold State Coach. A further estimated 500 million watched it on television.

After a thanksgiving service at St Paul’s, the queen made history by walking to the Guildhall through Cheapside. She stopped to greet the enormous crowds who’d gathered along the route.

Elizabeth travels up Ludgate Hill in the City of London to a special service at St Paul's Cathedral.

The Jubilee also created legacy projects we still see in London today. The queen opened a new Silver Jubilee Walkway that passes central London landmarks. The Jubilee Gardens opened on the site of an old South Bank car park – where the 1951 Festival of Britain was held. And the Jubilee underground line opened in 1979 with light grey trains representing the ‘silver’ colour of the jubilee.

Informal street parties and souvenirs marked the occasion

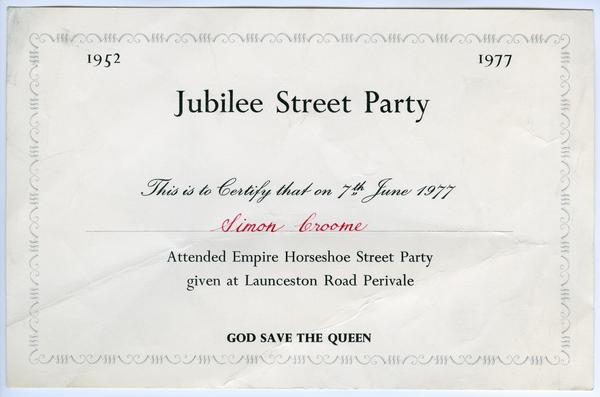

Street parties were organised by local communities across the country. Business boomed for companies selling paper plates and picnic wares, such was the demand to cater for these events.

Over 4,000 Jubilee street parties took place in London, including those on the Rock Estate in Islington. For their children’s tea party, they encouraged residents to decorate their homes and bring cakes, jellies and records for the affair.

“Royal events like these were very marketable and profitable”

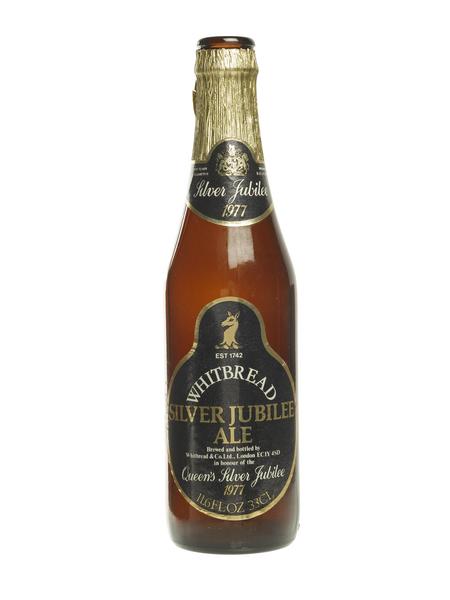

Many commemorative items were also sold to mark the occasion featuring official portraits of the queen, the Union Jack and other national or royal symbols. For many small and large businesses, royal events like these were very marketable and profitable.

But that year, shops and market stalls were also flooded with poorly made and overpriced souvenirs – often referred to as ‘jubilee junk’. The public were urged to “buy the right souvenir” bearing the Silver Jubilee emblem. The London Design Centre even recommended ‘acceptable’ products deemed worthy of the occasion.

A particularly punk protest

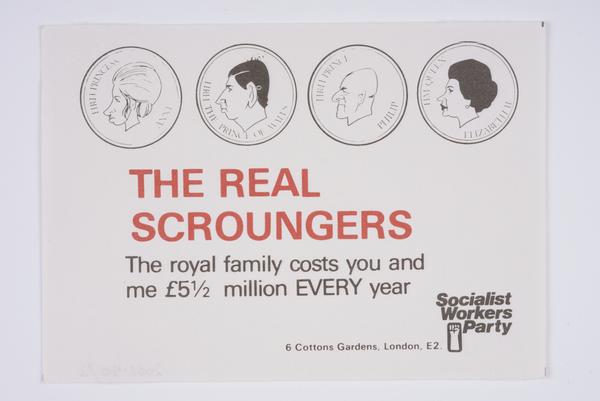

Not everyone celebrated the Silver Jubilee. Yes some welcomed the celebrations as a distraction from the economic struggles of the ‘70s. But others objected to their cost. In this so-called ‘decade of discontent’, many began to question the role of the monarchy in British society.

“There is no future in England’s dreaming”

Sex Pistols

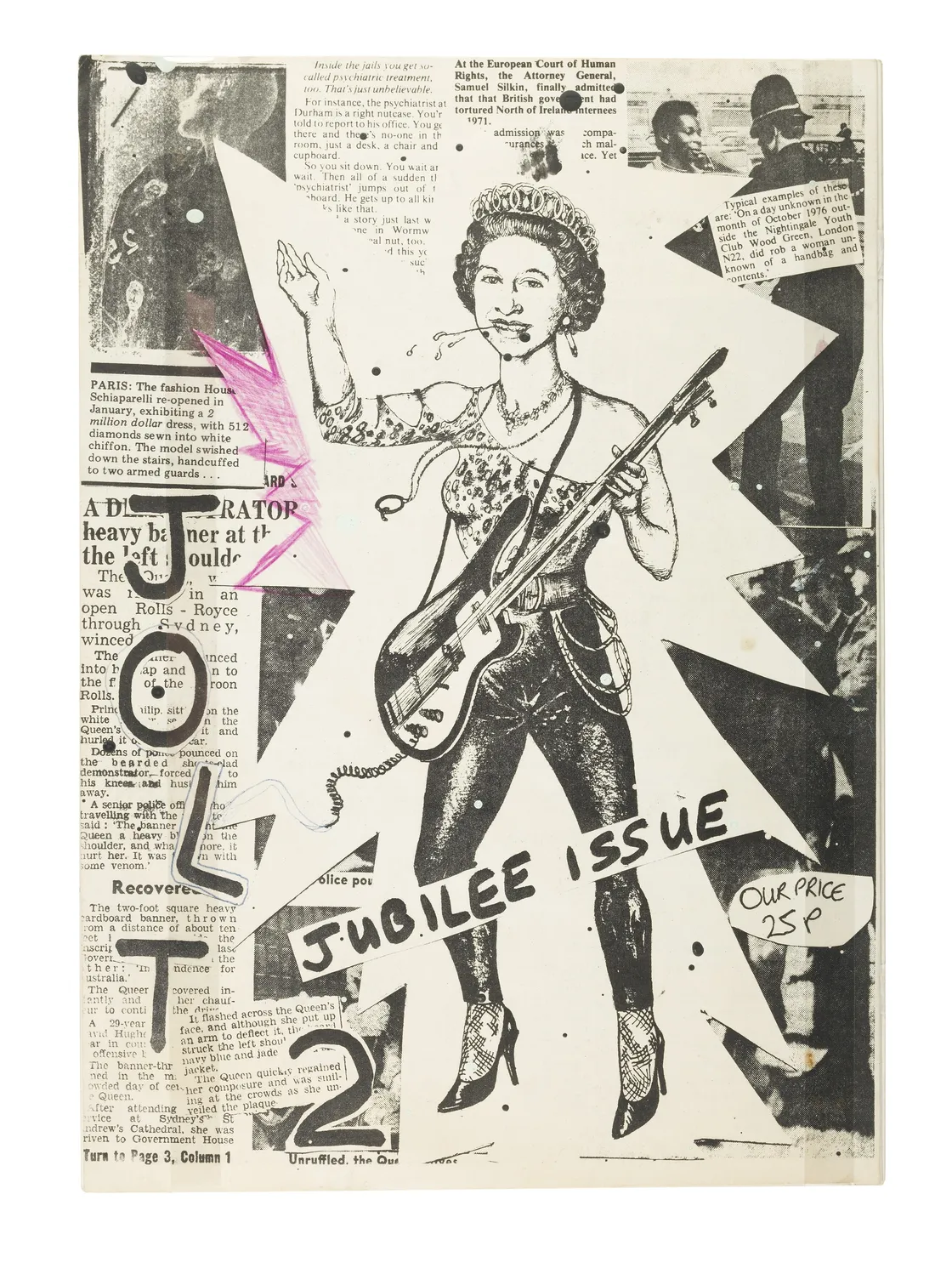

British punk pioneers the Sex Pistols released their most famous – and controversial – anthem God Save the Queen on 27 May 1977. It attacked the monarchy and compared Britain to a “fascist regime”. “There is no future in England’s dreaming,” they sang.

The Queen goes punk in this Silver Jubilee issue of the punk fanzine Jolt 2

The band even tried to perform the song from a boat on the Thames during the official jubilee celebrations on 7 June. But the police were called and their manager, Malcolm McLaren, was arrested.

The Socialist Workers Party also launched their Stuff the Jubilee campaign focusing on the rising costs of the royal family. They spread their message through flyers like these in the collection. These were probably distributed at anti-jubilee events like the People’s Jubilee at Alexandra Palace in north London, organised by anti-establishment and anti-monarchist groups, including the Communist Party of Great Britain.