The origins of Notting Hill Carnival

Notting Hill Carnival’s annual celebration of Caribbean culture attracts over a million people of all backgrounds for parades, music, dancing and food.

Notting Hill

Since 1966

London’s biggest street festival

Every year on August bank holiday weekend, the streets of Notting Hill in west London are transformed by the world’s second largest street carnival.

Now part of London’s cultural calendar, this annual expression of identity began with the Windrush Generation – Caribbean people who, from 1948, came to help rebuild post-war Britain.

Those who settled in Notting Hill faced racism and violence. So activists fought back, organising events to unite people. At an outdoor festival in 1966, a steel band drew a crowd as they roamed through the streets.

By the 1970s, Caribbean masquerade traditions provided the mesmerising costumes, while soca, calypso, dub and reggae gave carnival its thumping soundtrack.

Notting Hill in the 1950s

In the 1950s, Notting Hill was a poor area with terrible housing. The Black community there was one of London’s largest, but they faced blatant discrimination and abuse, including being refused jobs and housing.

In 1958 gangs of white men began attacking Black people. Fascist groups moved into the area to capitalise on the tensions, and in 1959, Kelso Cochrane, an Antiguan man, was killed in a racist murder.

A man and a woman at the Piss House Pub, Notting Hill in 1967.

These events attracted anti-racist activists to Notting Hill – who used marches, graffiti and public meetings to heal the divisions.

On 30 January 1959, Claudia Jones, an activist and newspaper editor, organised the first Caribbean carnival at St Pancras Town Hall in Camden. It was held in January to match the annual carnival in the Caribbean island of Trinidad – but the cold British weather meant it had to be held indoors.

Carnival hits the streets

The 1966 Notting Hill festival was the street party which created the Notting Hill Carnival we know today.

It was started by a local social worker – Rhaune Laslett – who says the idea came to her in a dream: “I could see the streets thronged with people in brightly coloured costumes, they were dancing and following bands and they were happy… men, women, children, black, white, brown, but all laughing.”

Laslett wasn’t of Caribbean heritage herself, and the first festival wasn’t centred around Caribbean identity. But, wanting to bring together Notting Hill’s many communities, she invited Trinidadian musician Russell Henderson and his steel band to perform.

When they started walking through the surrounding streets, the familiar sound of their music brought people of Caribbean heritage out of their homes to follow the band as they moved.

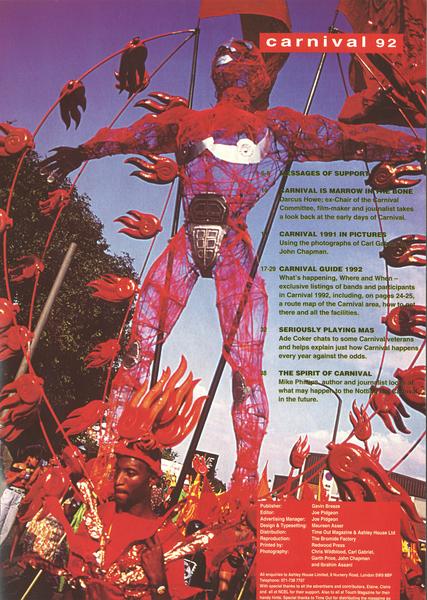

The 1970s: sound systems and mas bands

The carnival became an annual event, and the influence of Caribbean culture grew.

The 1973 carnival, organised by Leslie Palmer, was a significant turning point. The festival was more pan-Caribbean, involving performers with links to Dominica, Grenada and St Lucia. More masks and costumes were worn, some designed by experienced masquerade-makers from Trinidad.

“We brought carnival to Britain in our bones”

Darcus Howe

Static sound systems and live music stages were also added, reflecting the popularity of reggae and dub music. “The sound systems were the voice of the youth,” said Palmer.

Helped by radio broadcasts of the event, the carnival was drawing over 150,000 people by 1976.

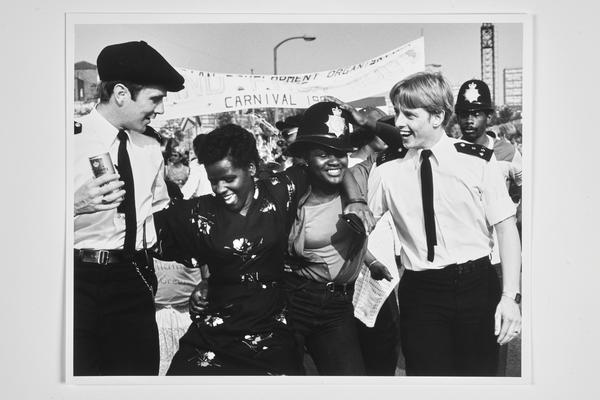

The police at Notting Hill Carnival

The 1970s also brought an outburst of violence. In 1976, existing tensions between the police and Black Londoners led to a larger police presence at carnival. The tension partly stemmed from the “sus” law, which police used to search and arrest anyone they felt was intending to commit a crime. The law was unfairly used to target young Black men.

The police’s show of force at Notting Hill angered the crowd and violence broke out, with police clashing with young carnival-goers. In this print from our collection, the artist Tam Joseph captured the feeling of being trapped.

In the decades afterwards, the police changed their approach, keeping a lower profile and encouraging officers to embrace the fun of the event.

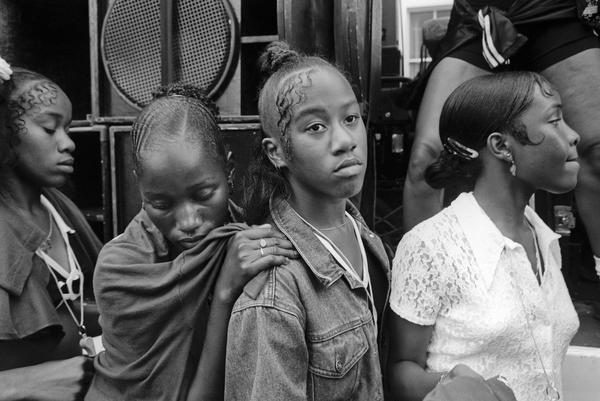

The masquerade tradition

Among a number of photos of the Notting Hill Carnival from the 1990s by Peter Marshall, one shows the mas – or masquerade – costumes which are still a core part of today’s parade.

The mas tradition stretches back to 19th-century Trinidad, and the first carnival celebrating the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act. “We brought carnival to Britain in our bones,” said writer and broadcaster Darcus Howe. “Carnival wasn’t a memory, it was an instinct.”

Masquerade costumes allow the wearer to disguise themselves and take on a different character. Every year, mas bands gather to create and coordinate their costumes as a group, each choosing their own theme and competing for prizes.

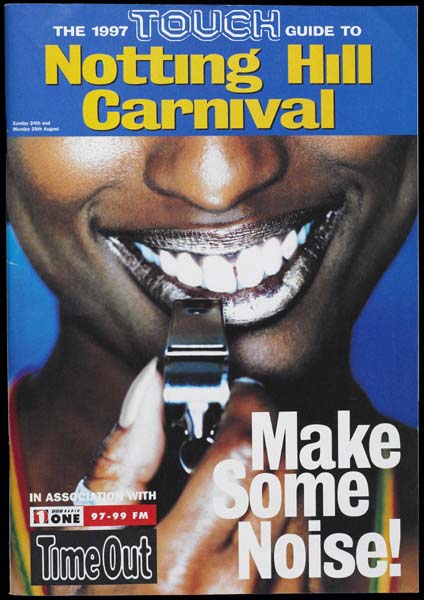

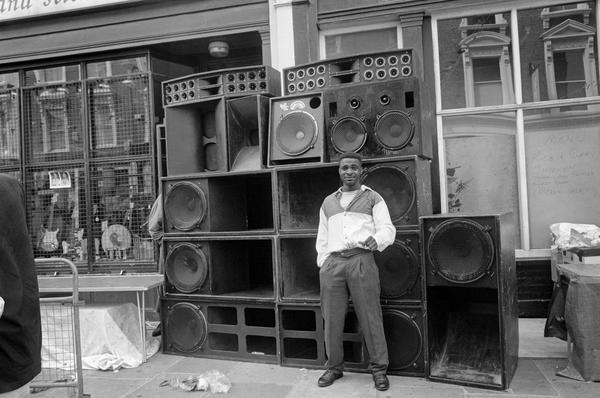

Notting Hill’s sound systems

Notting Hill has its own sonic identity – a mixture of whistles, steel bands and thumping sound systems.

The music still has a strong Caribbean influence, but nowadays the sound systems – carefully constructed speaker arrangements – blast all sorts of music, not just bass-heavy genres like reggae, dub, dancehall and jungle.

A 1997 issue of Time Out from our collection includes a map to help people find the different sound systems. Our collection also includes a series of photos by Eddie Otchere following Channel One sound system, who have taken part since 1983, and can be found on the corner of Leamington Road Villas and Westbourne Park Road.