Oliver Cromwell: The man who could have been king

After winning the Civil Wars (1643–1651) for Parliament and fighting in Ireland, Oliver Cromwell became lord protector, and was offered the throne.

1599–1658

One of British history’s most divisive figures

Outside Westminster Hall, on Cromwell Green, there’s a statue of the soldier and politician Oliver Cromwell. For some, he’s a hero of liberty and the parliamentary system, the man who helped overthrow and execute King Charles I.

But the stories of people memorialised by statues are rarely so simple. Cromwell led the massacre of Catholics in Ireland and Scotland, and some prefer to label him a dictator.

The truth is, the man behind the statue is one of the most significant and controversial figures in British history.

“A few honest men are better than numbers”

Oliver Cromwell, 1643

Who was Oliver Cromwell?

For anyone fascinated by the Tudors, the first fact to know is that Oliver Cromwell was a distant relative of Henry VIII’s chief minister, Thomas Cromwell. The Tudor politician was partly responsible for the wealth of Oliver’s family.

Oliver was born in Huntingdonshire, near Cambridge, in 1599 – almost 100 years after Thomas. Very little is known about his early life.

Oliver became a member of Parliament in 1628. But his first spell didn’t last long, as Parliament was quickly dissolved by Charles I.

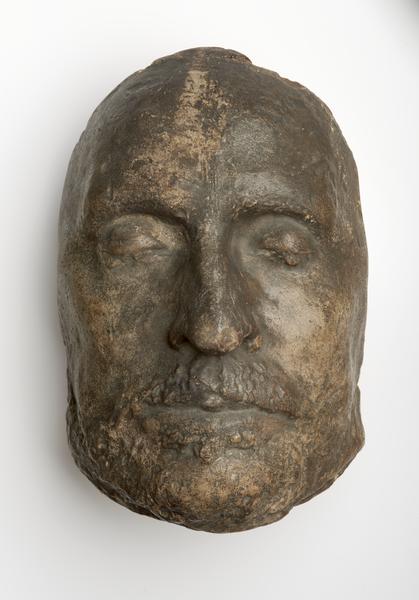

The phrase "warts and all" is said to have started with Cromwell's request to be painted accurately.

Civil War soldier

In the 17th century, divisions between Parliament and King Charles I led to the English Civil War, which lasted from 1642 until 1651.

Cromwell became a soldier in the Parliamentary forces, rising to second-in-command of their New Model Army by 1645. Along the way, Cromwell earned the nickname Ironside. In a 1643 letter, he argued that high class “gentlemen” weren’t necessarily better soldiers, and “a few honest men are better than numbers.”

This 19th-century oil painting shows Cromwell fighting at the Battle of Marston Moor in 1644.

Charles I surrendered during the war. He was convicted of high treason, and was executed in 1649 – Cromwell signed the king’s death warrant.

Fighting didn’t stop there, and Cromwell continued Parliament’s battle for control. He led the invasion of Ireland in 1649, including the infamous massacres at Drogheda and Wexford.

Could Cromwell have been king?

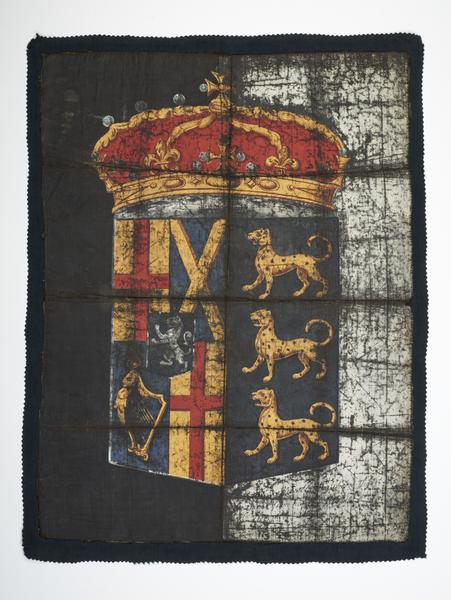

The Civil Wars made Cromwell a hero. With no king around, in 1653 he was sworn in as lord protector – the ruler of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland.

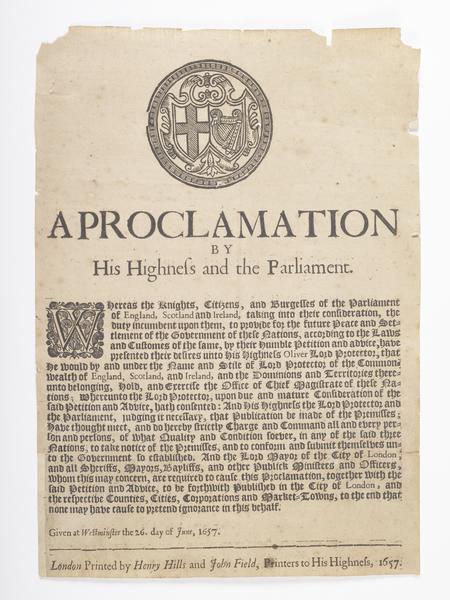

It was a unique moment in British history: a time when the monarchy was replaced by something new. Our collection contains a record of the announcement, printed in London, and rare coins featuring Cromwell’s face.

Cromwell could even have been king. He was offered the throne by Parliament. He refused, and was named lord protector again in 1657.

Just like a ruling king or queen, Cromwell had coins minted showing his face.

How did he die?

Cromwell died in 1658, aged 59. It’s thought he died of pneumonia, triggered by malaria. He was buried in Westminster Abbey.

A wax impression was taken of his face to make plaster death masks – one of them is in our collection.

A plaster death mask made from a mould of Oliver Cromwell's face.

Cromwell’s son Richard became lord protector. But, lacking the same support, he soon resigned.

Charles II was invited to restore the monarchy in 1660. In an act of revenge, Cromwell’s body was dug up from Westminster Abbey, and hanged at Tyburn, London’s infamous execution site. The head was cut off and displayed on a spike outside Westminster Hall.

What religion was Oliver Cromwell?

In his 30s, Cromwell became a radical Independent Puritan with strong anti-Catholic beliefs.

His time in Ireland earned him a reputation for ruthlessness, especially against Catholics. He oversaw the transfer of property from Irish Catholics to British Protestants. He banned the public practice of Catholicism. And Catholic priests were killed.

But as lord protector, his approach to religion was tolerant for the time. He argued that Jews should be allowed to practise openly in England, and that Irish Catholics could worship in private.

London Museum holds a huge variety of Cromwell-related objects from the Tangye Collection.