Three myths about the Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London is an extremely well known disaster. It’s been researched extensively ever since 1666. However, there are still some enduring myths which need to be busted.

City of London

1665–1666

Smoke without fire

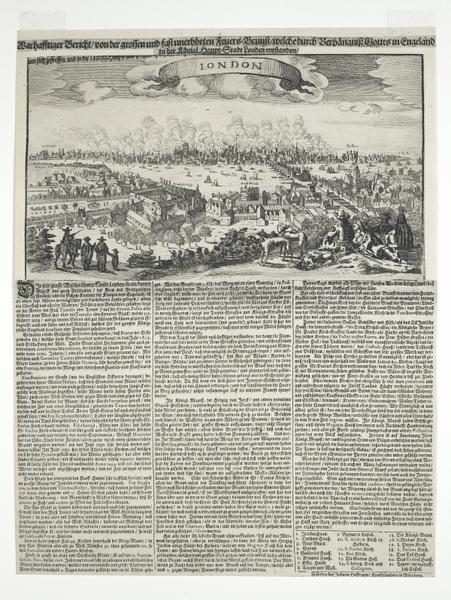

Give a famous historical event almost 400 years to smoulder in our imagination, and some inaccuracies are bound to set in.

Many people think that the Great Fire of 1666 stopped the Great Plague of 1665. Others believe the fire spread across London’s thatched roofs. And it’s often said that the Great Fire introduced brick buildings to London.

None of these are true.

Myth: The fire stopped the Great Plague

This is the myth that we hear most often. People may have read it in a children’s book or heard it at school.

The idea is that there was a silver lining to the tragedy of the fire, as it ended the Great Plague that swept the city from 1665–1666.

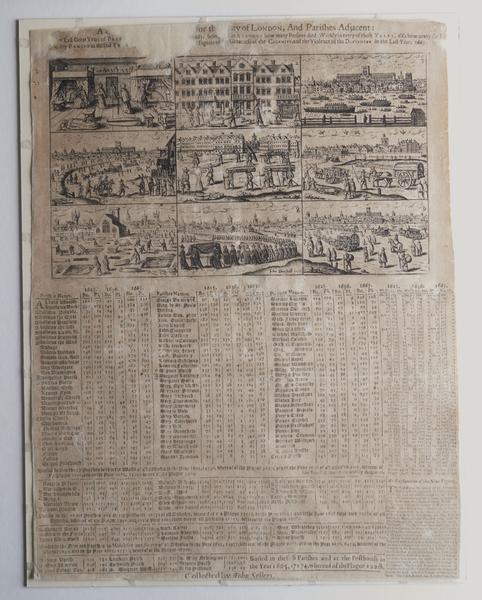

The epidemic was the last major outbreak of the bubonic plague in London. It killed 100,000 Londoners – about 20% of the city's population.

In this myth, the fire is supposed to have wiped out London’s rats and fleas, which spread the plague, and burned down the dirty houses which were a breeding ground for the disease.

If anyone asks you about this myth, you can tell them that it’s not true. Here’s why:

- There were no major improvements to hygiene or the systems for getting rid of human waste afterwards.

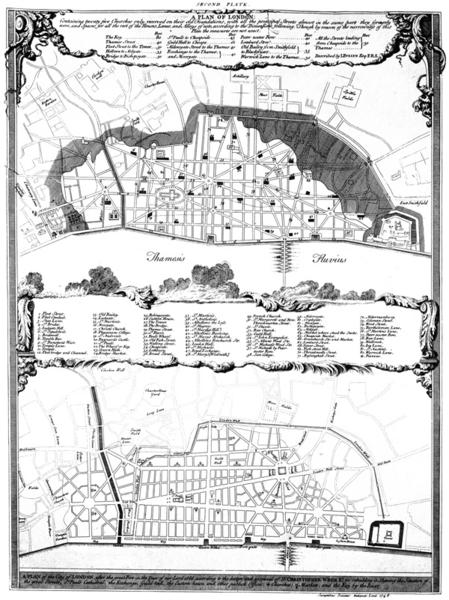

- Many of the areas worst affected by the plague, such as Whitechapel, Clerkenwell and Southwark, weren’t destroyed by the fire.

- The number of people dying from plague was already falling from the winter of 1665 onwards.

- People continued to die from plague in London after the Great Fire was over.

This myth seems to have grown up because the two disasters were so close together, and because the Great Plague was the last major outbreak of the disease in this country.

We’re still unsure why the plague did not return to our shores after it faded out in the 1670s, but it wasn’t due to London’s terrible fire.

“there were many brick buildings in London before 1666”

Myth: The fire spread across thatched roofs

Thatch roofs made with reeds or straw had actually been banned within the City of London since 1189. These rules were reinforced after a terrible fire in 1212 killed around 3,000 people.

Shortly after this fire, authorities ruled that all new houses had to be roofed with tiles, shingles or boards. Existing thatched roofs had to be plastered.

The medieval rules appear to have been successful in preventing large-scale fires. John Stow, in his 1598 Survey of London, said that since the introduction of the rules, “thanks be given to God, there hath not happened the… [same] consuming fires in this city as before.”

By 1666, the vast majority of houses in London had tiled roofs. If some thatched buildings remained, they weren’t noted as a cause of the fire.

Two accounts from the time mention timber buildings as a problem – but not thatch. One, who signed their name as Rege Sincera, wrote about “the weakness of the buildings, which were almost all of wood, which by age was grown as dry as a chip”.

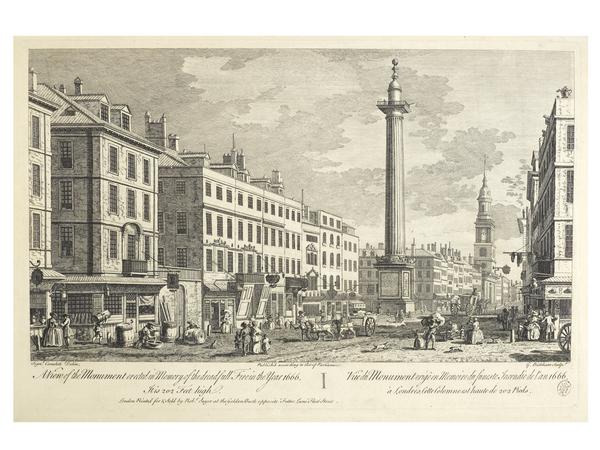

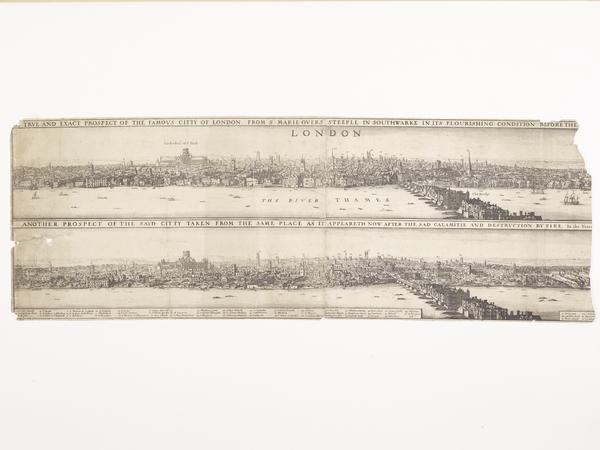

Myth: London was rebuilt in brick and stone

It’s true that after the fire the 1667 Rebuilding Act stated that “all the outsides of all buildings in and about the said city be henceforth made of brick or stone”.

But there were many brick buildings in London before 1666. Even on Pudding Lane where the fire began.

In March 1605, King James I said that no one should build a new house in London unless it was made from brick or stone because he needed timber for the navy’s ships.

Uptake was slow. Later proclamations repeated this demand several times. In October 1607, James I stated that new brick or stone buildings would “beautify his… city, and be less subject to danger of fire”.

As these rules only applied to new houses, and appear to have only been occasionally obeyed, the Great Fire became the opportunity to enforce and refine existing rules.

The disaster affected such a large area that thousands of brick houses had to be built to replace those that had been destroyed. This has left us with a false impression that the fire introduced brick to London.