The Metropolitan Police: From 1829 to today

The Metropolitan Police Force was founded in 1829. With responsibility for the majority of London, it became the country’s first professional police force to take a city-wide approach.

New Scotland Yard, City of Westminster

1829 – today

Police officers at Downing Street, Westminster, in 1909.

London’s long arm of the law

The Metropolitan Police Force – also called the Met – replaced the inefficient local system of parish constables, who were unable to coordinate across the city’s different areas.

Over the next 200 years, the Met transformed into a far larger, more diverse, more sophisticated police force, with units specialising in combating drugs and terrorism.

As London has evolved, the Met’s tried to keep pace. But from the very beginning, Londoners have questioned and challenged the force. Now more than ever, policing London is an immense and complex task.

What came before the Met police?

At the start of the 18th century, London didn’t have a professional police force. Combatting crime was the responsibility of local parishes, the small districts centred around churches.

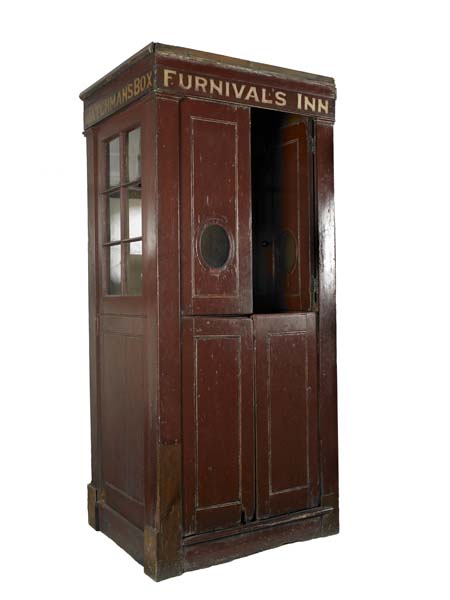

Parishes hired watchmen to patrol the streets and stand guard in boxes, like the one in our collection from the early 19th century. If there was rioting, the army stepped in.

As the 18th century went on, more effective approaches emerged. In 1748, a group called the Bow Street Runners was formed by the local court to capture criminals and prevent highway robbery.

And in 1798, the Thames River Police was formed to stop goods being stolen from the docks.

The Bow Street Runners making an arrest.

“As well as their top hats, the first officers were given a truncheon and a rattle”

Why was the Met Police founded?

London was a city of nearly two million people by the middle of the 19th century, and politicians thought that crime was increasing. After reforms at the start of the century, fewer crimes were punished with public execution, meaning authorities could no longer rely on the fear of death to prevent crime.

The home secretary Robert Peel argued that a full-time, paid police force coordinating across the city was the solution.

In 1829, Peel’s Metropolitan Police Bill became law, creating the Met. This new force, headquartered at Scotland Yard in Whitehall, became responsible for most of London – but not the City of London, which still has its own force today.

The original Scotland Yard, at the Met's first headquarters in Whitehall.

State control and public opinion

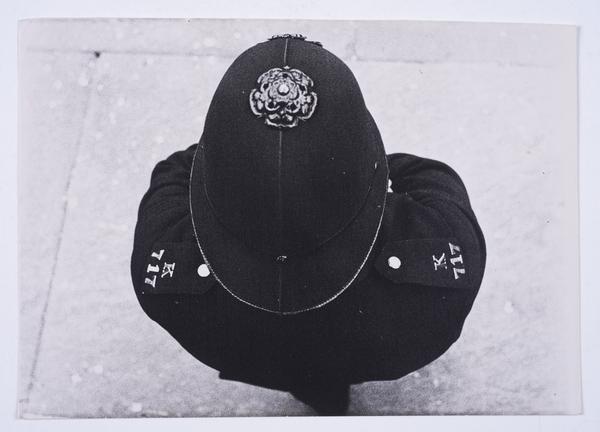

At the time, many people believed that the Met was just a new way for the government to control them. To counter this impression, officers didn’t carry guns, and wore top hats to make them look less like soldiers.

Still, when they first appeared on the streets, police officers were attacked and abused.

What did the first Met police officers do?

As well as their top hats, the first officers were given a truncheon and a rattle – later replaced by a whistle – to attract attention when chasing criminals. Their high collars contained a leather band, meant to protect them from attacks from behind.

The officers were asked to walk around the neighbourhood at a slow pace, hoping to prevent crime before it happened.

In 1842, the Met's detective department was set up to give the force a better chance of solving crime too.

An early test came in 1888, when the Met was criticised for failing to catch the serial killer known as Jack the Ripper. The cartoon below, from the magazine Punch, makes its point by showing a blindfolded officer failing to catch criminals.

Women join the Met

To start with, only men were hired as police officers.

In the 1880s police matrons were hired to supervise women and children in police stations and courts. And during the First World War (1914–1918), two groups of volunteers formed: the Women’s Police Service (WPS) and the Voluntary Women Patrols, organised by the National Union of Women Workers.

Members of the volunteer Women's Police Service in 1915. Although they worked with the Met, the WPS were not given the power to make arrests.

The WPS included former Suffragettes, campaigners who had clashed with police in their fight for the vote. That history meant WPS volunteers never became part of the Met.

But in 1919, 110 women from the Voluntary Women Patrols did. At first, they were required to patrol in pairs, with a pair of male officers following close behind.

The Met’s women police officers gained the power to make arrests in the 1920s. In 2024, 31% of officers were women.

Policing a changing London

London became a far more diverse city after the end of the Second World War in 1945. People from across the world made the city their home, including many from the former colonies of the British empire.

Minority ethnic groups have faced discrimination from many parts of British society – including the Metropolitan Police. This treatment has created tension between communities and the police which remains unresolved.

One significant moment came in 1998, when an inquiry found evidence of institutional racism in the Met’s investigation of the murder of Stephen Lawrence. It suggested the case had been handled differently because Lawrence was Black.

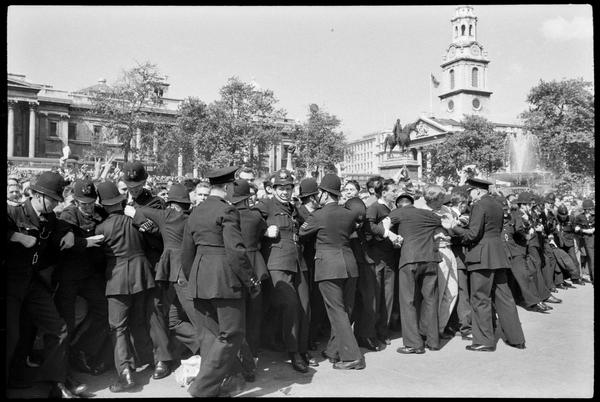

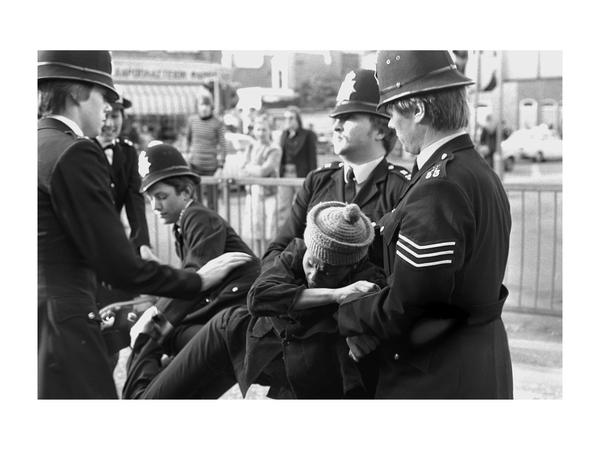

Uprising

The Met’s treatment of London’s Black British and British South Asian communities, together with social and economic deprivation, has occasionally led to mass uprisings. In the 1970s and 1980s, there was rioting in Brixton, Southall and Tottenham.

In 2011 the killing of Mark Duggan, a Black man, by police led to further anger, protest and rioting in Tottenham, which then spread across the country.

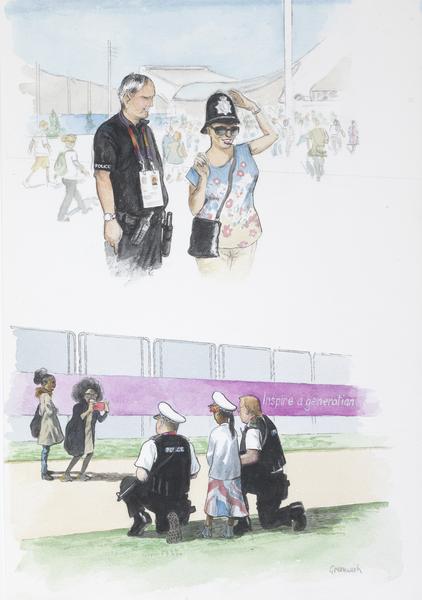

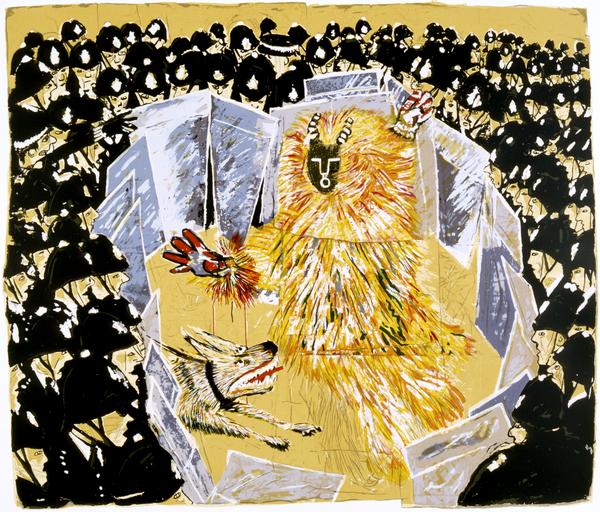

In the artworks above by Mike Hawthorne and Tam Joseph, which show the Brixton Uprising and Notting Hill Carnival, the strained relationship between the Black British community and the police is clear. It’s just as clear on the red paint-spattered riot shield in our collection, used during the 2011 Tottenham riots.

The Metropolitan Police continues to be challenged on the way it operates. In 2021, Sarah Everard was murdered and raped by a serving Met police officer.

The case caused a public outcry, and led to an official review into the Met’s behaviour and culture. In 2023 Baroness Casey's report found that the Met was institutionally racist, misogynistic and homophobic.