Masquerades in London’s pleasure gardens

Wearing elaborate disguises, the rich, famous and infamous would meet to dance, flirt and intrigue until the early hours of the morning.

Vauxhall & Chelsea

1700s & early 1800s

Dancing in disguise

One of the most notable – and notorious – features of London’s pleasure gardens was the masquerade, or fancy dress ball. It was also known as the ridotto, from the Venetian private gambling salons where visitors wore masks to conceal their identities.

Masquerades allowed some social mixing that wouldn’t have happened outside the pleasure garden. Under the cover of masks, men and women from different social backgrounds could dance and mix freely together.

This caused quite the panic among moralistic groups who saw it as a challenge to, what they believed was, the natural order of society.

Why did pleasure gardens start hosting masquerades?

Masquerades were introduced to London by the Swiss count Johann Jacob Heidegger in the early 1700s. He first came across them in Italy and originally staged them in London theatres. When Vauxhall Gardens opened to the public in 1729, and Ranelagh Gardens in 1741, they became obvious venues to host these lavish and fashionable entertainments.

The Pantheon on Oxford Street was famous for its masquerades in late Georgian London.

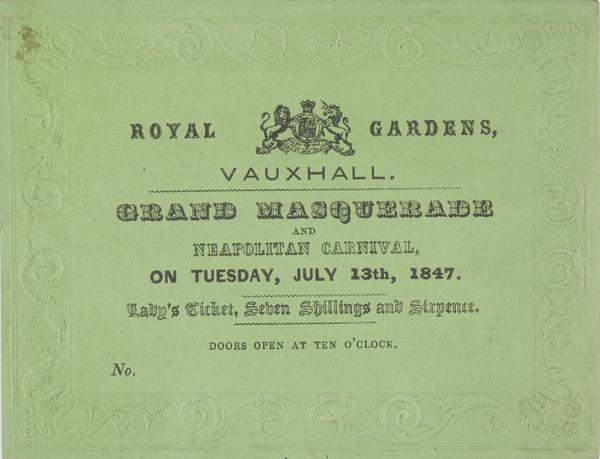

Masquerades were immediately popular with those who could afford the expensive tickets. They’d often cost as much as one guinea – a week’s earnings for a skilled labourer. If you were lucky, you could take advantage of the opportunity for disguise and sneak in.

“The prettiest spectacle that I ever saw… nothing in a fairy tale ever surpassed it”

Horace Walpole, 1749

Masquerades were staged to celebrate significant public events, such as the end of a war or a royal birthday. In 1749, Vauxhall hosted a masquerade to mark the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which concluded the War of the Austrian Succession. The politician Horace Walpole wrote that it was “the prettiest spectacle that I ever saw… nothing in a fairy tale ever surpassed it”.

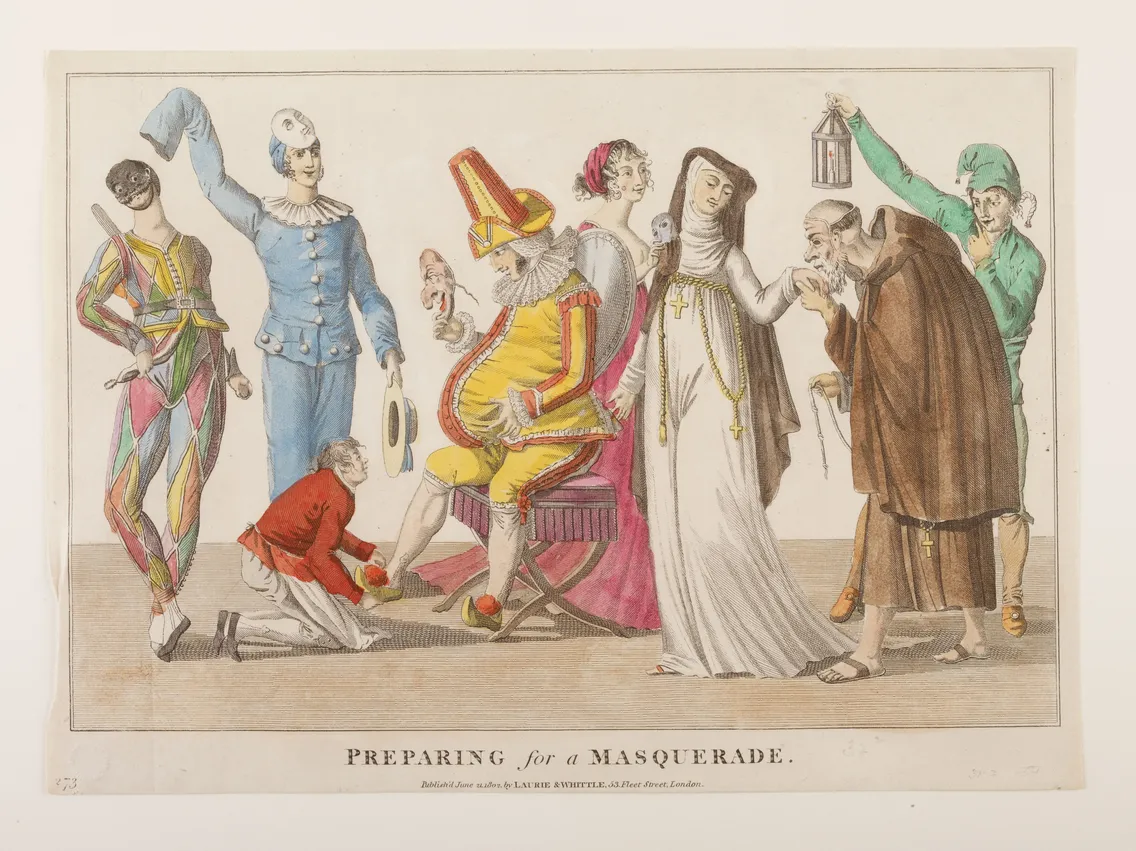

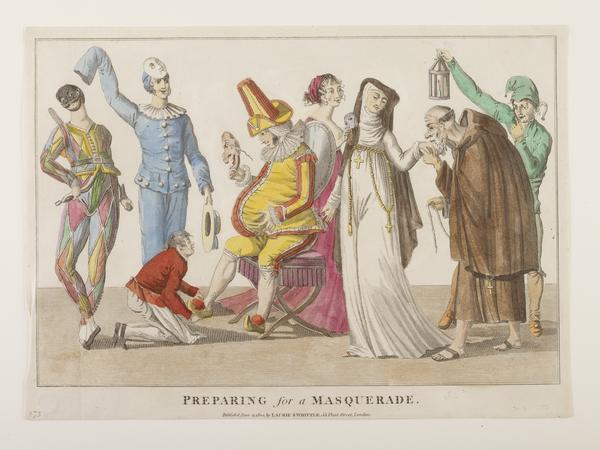

What did people wear at masquerades?

The costumes worn at masquerades were expensive and luxurious. They played on cultural references at the time – and were often ironic.

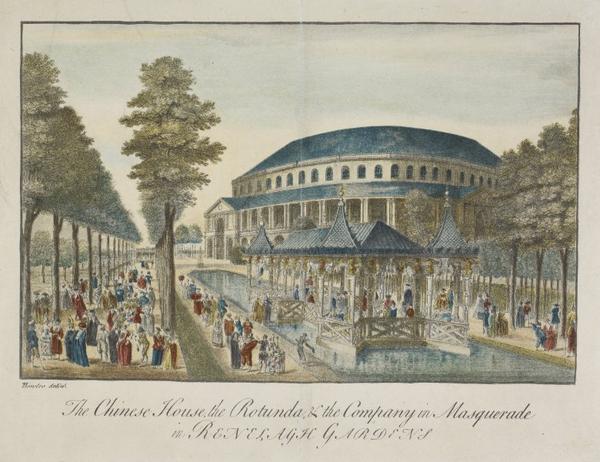

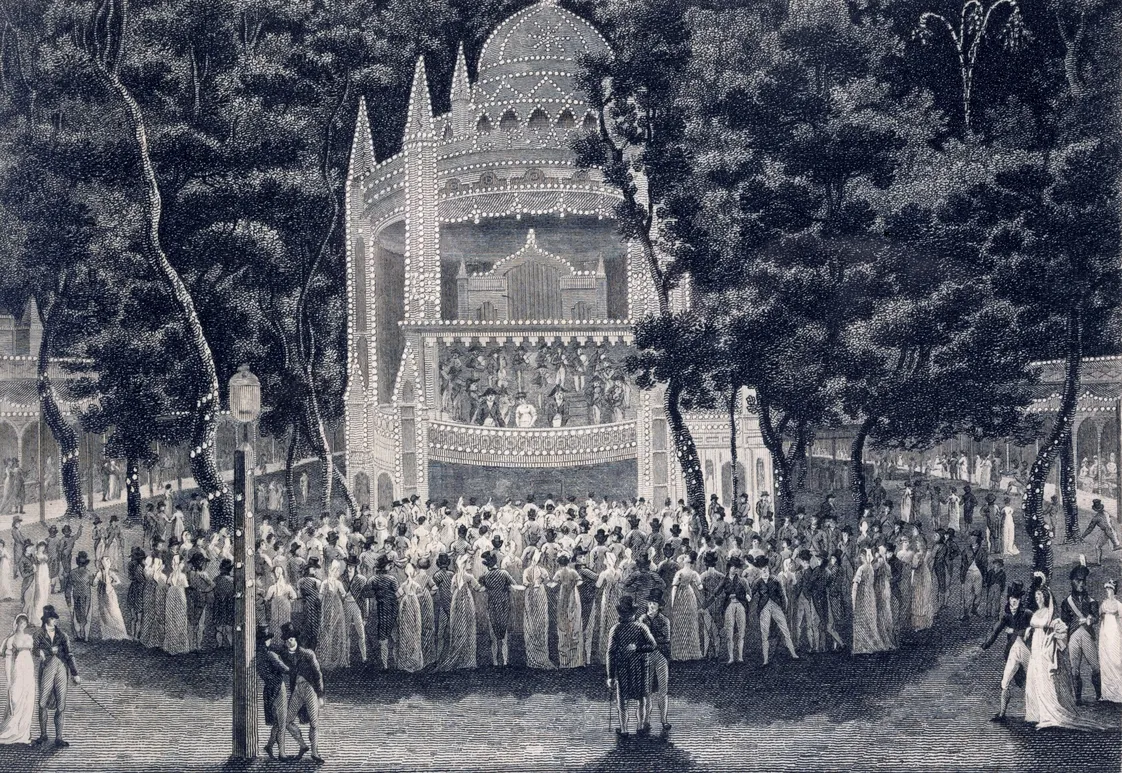

Costumed figures dance at a masquerades in Ranelagh Gardens.

Heroes and goddesses from ancient Greece and Rome were popular subjects. As were costumes representing traits such as ‘virtue’ or ‘truth’. National costumes of other nations, figures from folk songs and ballads, even animal costumes were all also frequently found on the dancefloor. And some guests just wore a long cloak known as a domino, in black or white silk, with their face disguised by a mask.

Traditionally, revellers would unmask at the end of the night. Part of the fun was to try and guess who wore which disguise.

Why were masquerades controversial?

Masquerades were very popular events. But some saw them as immoral, scandalous and unpatriotic. They were publicly denounced by Edward Gibson, the Bishop of London, who preached a sermon against them. Respected artists and novelists such as William Hogarth, Henry Fielding and Samuel Richardson also condemned them.

“By wearing a costume and a mask, you could step into another world for a few hours”

It was the idea of disguise that really sent critics into a panic. At a masquerade, the formal conventions of polite 18th-century society were suspended. By wearing a costume and a mask, you could step into another world for a few hours. Aristocrats were disguised as chimney sweeps and shepherds. Men dressed as women. And women dressed as men.

A woman returns from a masquerade looking a little worse for wear.

These moralists and conservative thinkers worried that the social norms which kept society functioning, such as social hierarchy and gender roles, would be compromised. If status could be gained or lost by simply pulling on some different clothes, wasn’t the entire social structure at risk?

In the end, the decline of masquerade’s popularity coincided with the increased public moralism of the early 1800s. Although ‘fancy dress balls’ remained a form of fashionable entertainment throughout the rest of the century, they were respectable and harmless affairs compared with the risqué, dramatic masquerades of a hundred years before.