Mary Seacole: Doctress of the Crimean War

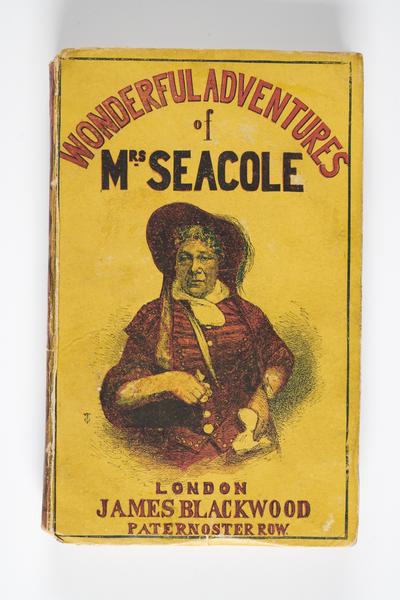

Mary Seacole became a hero in Victorian Britain for her work with soldiers in the Crimean War. She told her life story in her book, Wonderful Adventures of Mrs Seacole in Many Lands.

1805–1881

Humanitarian, herbalist, 'Mother' to sons at war

Mary Seacole was a businesswoman and “doctress”, a word she used to describe the traditional Creole herbal healing work she learned from her mother in Jamaica.

She was a very famous figure in mid-19th-century London and was widely known as Mother Seacole. Seacole was celebrated for her work caring for the British army during the Crimean War, a war fought by a coalition including Britain against Russia.

Much of what we know about Seacole comes from her autobiography, published in 1857 shortly after she returned from the war. An edition from 1857 is in our collection.

Though well-loved in her time, Seacole was lost to history after her death. Her memoirs weren’t reprinted again until the 1980s. But she’s now widely recognised for her work in the Crimean War. A statue commemorating her stands outside St Thomas’ Hospital in Lambeth.

An 1857 edition of Wonderful Adventures of Mrs Seacole, published in London.

Who was Mary Seacole?

Mary Seacole was born Mary Jane Grant in Jamaica in 1805 to a Scottish army father and a Creole mother. She married Edwin Seacole in 1836. He died in 1844, and her mother died soon after in 1846.

Seacole travelled on various business adventures in early adulthood – to the Bahamas, Cuba, Haiti and, on a few occasions, London. She wrote about the racism she experienced from “London street-boys who poke fun at my and my companion's complexion. I am only a little brown – a few shades duskier than the brunettes whom you all admire so much.”

Experience treating sick people as a ‘doctress’

In Kingston, Jamaica, Seacole gained a reputation as a doctress by treating people with fevers – including British army officers – who stayed at the boarding house she ran. She also gave remedies to people during outbreaks of the diseases cholera and yellow fever.

In 1851, Seacole travelled to Cruces in the Republic of New Granada (part of present-day Panama). Her half-brother owned a hotel there for people travelling to and from California searching for gold. She set up a restaurant at the hotel and also dispensed medicines and treatment to sick people during a cholera outbreak. In 1853, she started investing in gold there.

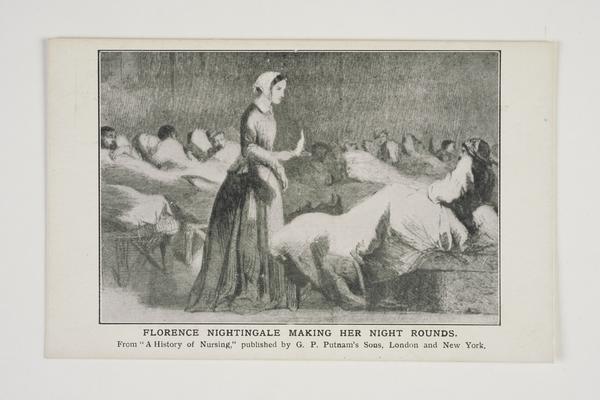

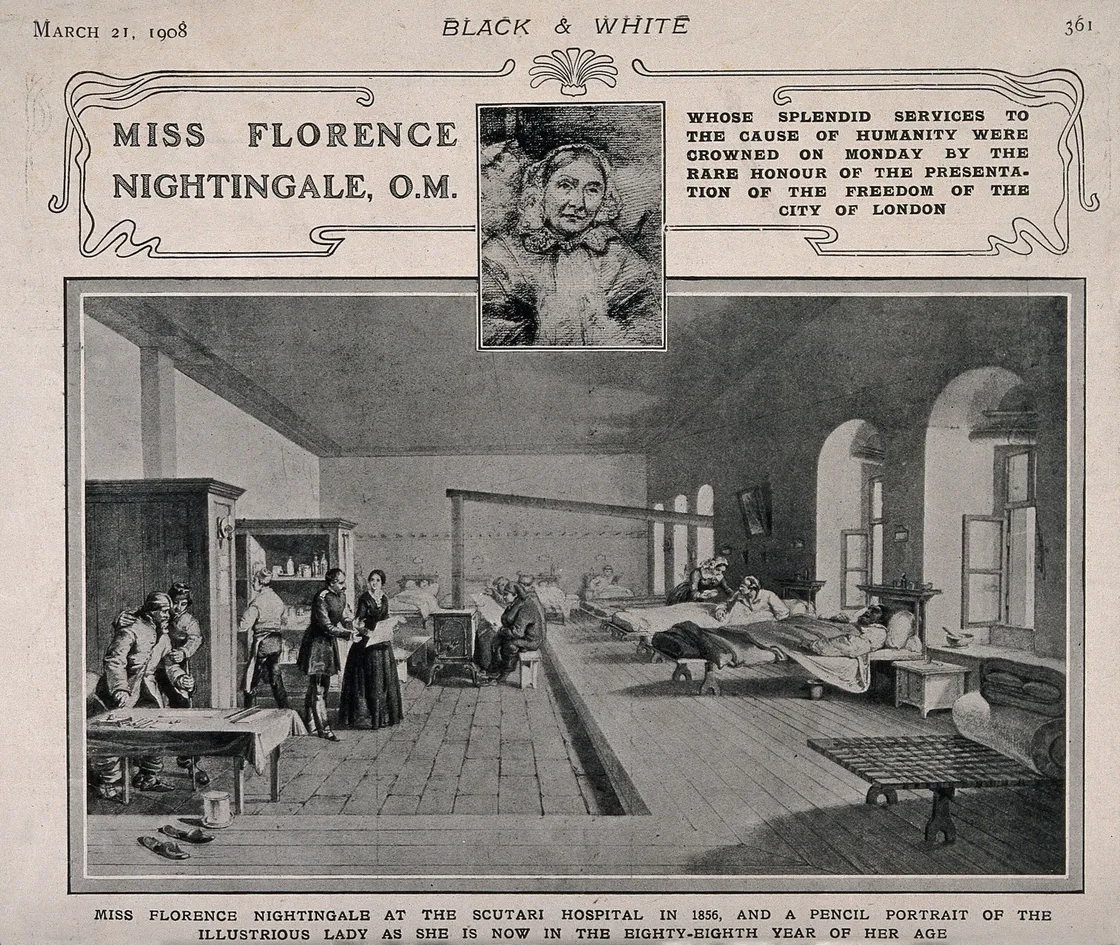

Florence Nightingale nursing soldiers at Scutari Hospital during the Crimean War.

Applying for war work in the Crimea

Seacole was in London looking after her gold stocks around the time Britain entered the war with Russia in 1854. She decided to go to the Crimea and help her “sons” there who were “suffering from cholera, diarrhœa, and a host of lesser ills”.

“Did these ladies shrink from accepting my aid because my blood flowed beneath a somewhat duskier skin than theirs?”

Mary Seacole

While she thought she was “well fitted for the work”, her attempt to apply in-person at the War Office to serve as a war nurse was unsuccessful. As was her offer to join Florence Nightingale’s team of nurses, who were already out in the Crimea working in British military hospitals.

“Did these ladies shrink from accepting my aid because my blood flowed beneath a somewhat duskier skin than theirs?” Seacole questioned in her autobiography.

Setting up the British Hotel

Undeterred, Seacole funded her own trip to the Crimea in 1855. She and Thomas Day, a relative of her late husband, set up the so-called British Hotel near where fighting had been in Balaclava.

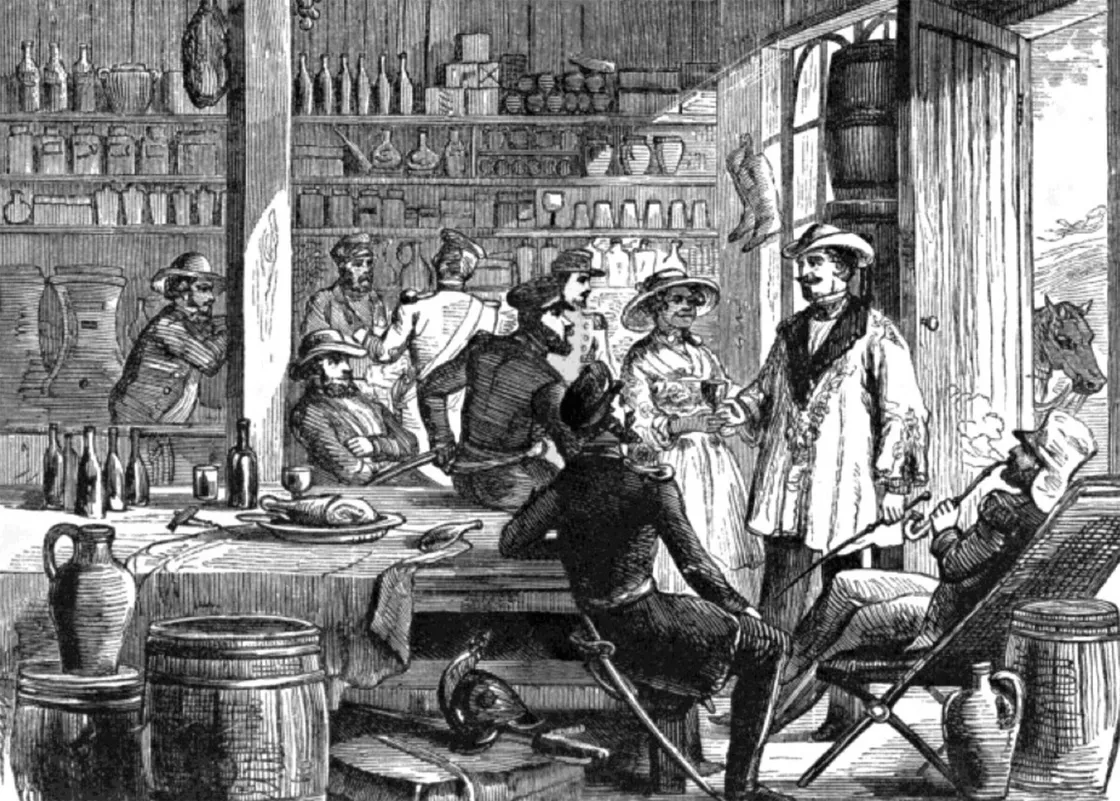

Mary Seacole meets French chef Alexis Soyer, who joined her in the Crimea to feed ill soldiers and advise on army cooking, in the British Hotel bar.

This ‘hotel’ was actually a storehouse, a canteen and resting place that brought comfort to, and lifted the spirits of, army personnel. Seacole and Day sold supplies and medicines to the army. And she also visited the battlefront to care for wounded soldiers. She gathered testimonies of those she cared for and cured in her book.

Seacole and her work in the Crimea became very well-known to British people, whether through press coverage by correspondents like The Times’ William Howard Russell, or the letters soldiers sent home. One report from Balaclava in the Standard commented on how much those at war “appreciate[d] ‘Mother’ Seacole, as she is affectionately called”.

Returning to England bankrupt but a hero

British troops were hastily evacuated from the Crimea in April 1856. Seacole and Day were left with leftover stocks of food and equipment – and outstanding debts. Soon after Seacole returned to England, she was declared bankrupt.

Both The Times and Punch magazine organised appeals to raise money to pay off her debts. In 1857, Russell wrote in The Times that she deserved these funds for her “courage, devotion, goodness of heart, public services, great losses undeservedly incurred”.

This 1857 illustration in Punch depicts Seacole as an admirer of the magazine and downplays her nursing activities by calling her a "vivandière", or canteen worker.

Around this time, Seacole was also writing her autobiography from her home in Soho Square. It was published in July 1857. There was a fundraising event at the Southwark pleasure garden Royal Surrey Gardens shortly after – but she received little of the money. Still, her Wonderful Adventures was a bestseller.

Seacole died in London in 1881 and was buried at St Mary's Roman Catholic Cemetery in Kensal Green.