Lost rivers: The Westbourne

The River Westbourne was one of northwest London’s cleanest waterways. It fed into spas, ornamental water features and drinking water supplies.

City of Westminster

Watercolour by artist Paul Sandby depicting the fields at Bayswater, with the Westbourne stream seen in the middle ground.

A source of London life and leisure

The Westbourne springs from Hampstead Health, flowing down through Hyde Park and into the River Thames near Chelsea Bridge. Before the 19th century, different sections of the river were known as either the Kilburn or the Bayswater, named after the areas it passed through.

Thanks to its small streams, the Westbourne was spared the industrial use and abuse that larger rivers like the Fleet endured. It was a source of fresh drinking water and was used to create decorative lakes and water features, like the Serpentine.

Eventually, like its other hidden river siblings, the Westbourne was incorporated into our modern sewer system.

Through rural pastures west of London

The route of the Westbourne was mostly rural up to the 1800s. The area was known for its watercress fields as well as streams, springs and reservoirs for drinking and washing.

Sandby paints the Bayswater Turnpike around 1807, with the stream of the Westbourne running under the road.

It wasn’t all sheep and idyllic pastures, though. Areas upstream of the Westbourne were also isolated and sometimes dangerous places. The Knight’s Bridge near Hyde Park had a reputation for highwaymen, robberies and even murders. So did Blandel Bridge, near modern-day Sloane Square, which earned itself the name ‘Bloody Bridge’.

London’s water supply

Like the nearby River Tyburn, the Westbourne was used as a source of fresh water to Londoners. Conduits were built from the 1430s to take water from springs alongside the Westbourne into the City of London in underground tunnels.

In the 1100s, a priory was built at Kilburn. It supplied drinking water – and fish ponds – to locals and pilgrims who stopped off on their way to and from London.

By the end of the 16th century, a nearby spring with medicinal water was discovered. Named the Kilburn Wells, the water was thought to help stomach problems caused by “over-indulgence in the good things of this world”, according to one early-20th-century doctor.

In 1723, the Chelsea Waterworks Company was set up to provide drinking water to the West End. Water from the Westbourne supplemented water from the Thames. Notice the well-dressed figures visiting the waterworks in the print above? This suggests that it was even a visitor attraction in the 18th century.

A feature of west London entertainment

Thanks to the Westbourne’s mostly clear water, the river was used to create ponds and canals that became features of London’s leisure scenes.

“a happy spot… celebrated for its rural situation… and the acknowledged efficacy of its waters”

The Public Advertiser, 1773

In 1714, the spring at Kilburn Wells was enclosed and turned into a spa, which also featured music and entertainment. It was described by one London newspaper as “a happy spot… celebrated for its rural situation… and the acknowledged efficacy of its waters”.

In 1730, on the request of Queen Caroline, the Westbourne was dammed to create the Serpentine lake in Hyde Park. This oil painting shows Londoners socialising around it and boating on it – just like they do today. In the freezing winters of the 1700s and 1800s, it was even a popular spot for ice skating.

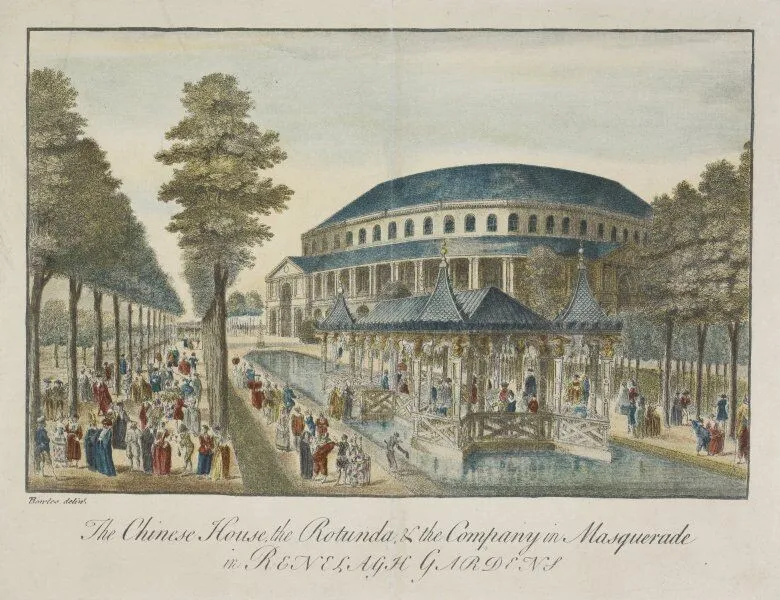

The Westbourne filled the ornamental canals of Ranelagh Pleasure Gardens. Opened in 1742, Ranelagh was a place where wealthy west Londoners could get together, dance and listen to music. One visitor reported the “wonder” of the canals as they reflected “thousands of gay lamps” at night.

Turned into a sewer

Into the 1800s, London developed northwards and westwards. The Westbourne became increasingly polluted by sewage from new neighbourhoods built in places like Belgravia and Bayswater. By the 1860s, it was too dirty to supply the Serpentine with clean water. You wouldn’t want to drink from it, either.

The lower section of the river from Sloane Square to the Thames was covered over in the mid-19th century and named the Ranelagh sewer. You can spot the original pipe carrying it through to the Thames at Sloane Square Underground Station.