Lost rivers: The Walbrook

Once a vital artery of both Roman and medieval London, the Walbrook has been buried underground since the 1500s.

City of London

London’s long lost river

Flowing from Shoreditch, under the Bank of England, and into the Thames at Cannon Street, the River Walbrook had a huge impact on London – despite its relatively small size.

Like many of London’s lost rivers, it now exists as a sewer. But the Walbrook was a significant feature of both Roman and medieval life. It fueled industry, influenced the administration of the city and was even considered sacred at one point.

Layers and layers of London’s history have been built over the top of the Walbrook. But thanks to excavations over the past 100 years, objects from the riverbed have provided a rich window into London’s distant past.

The fabric of Roman London life

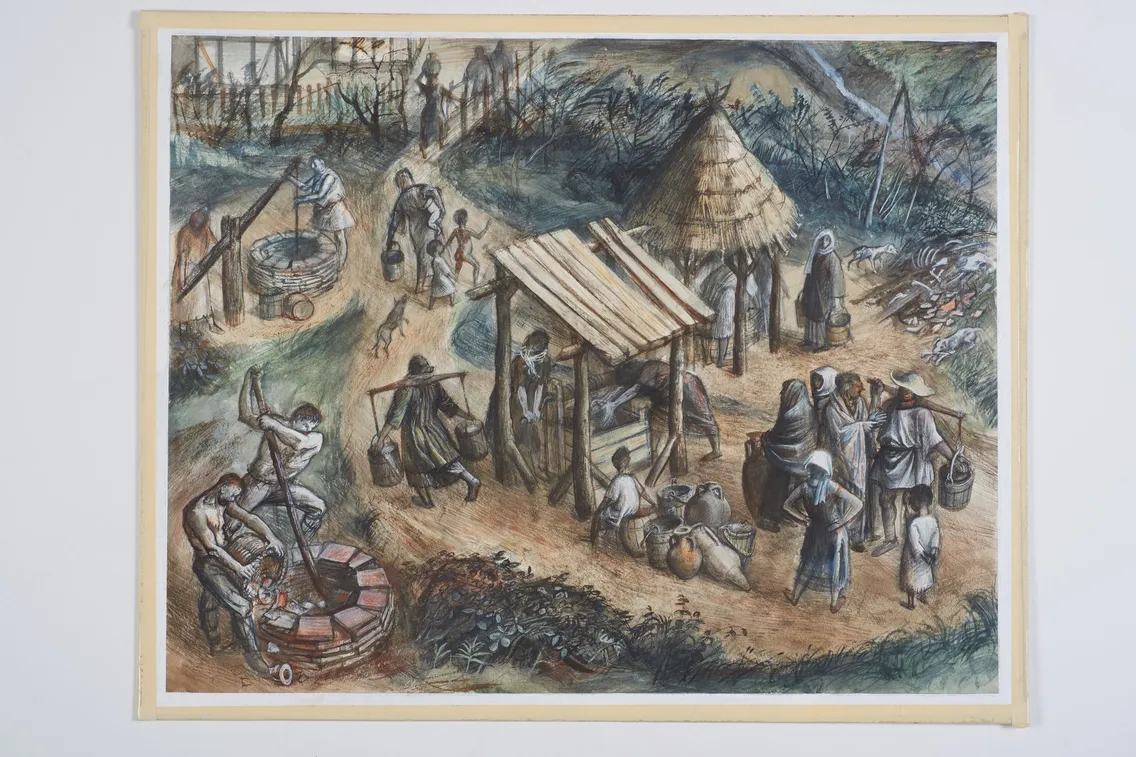

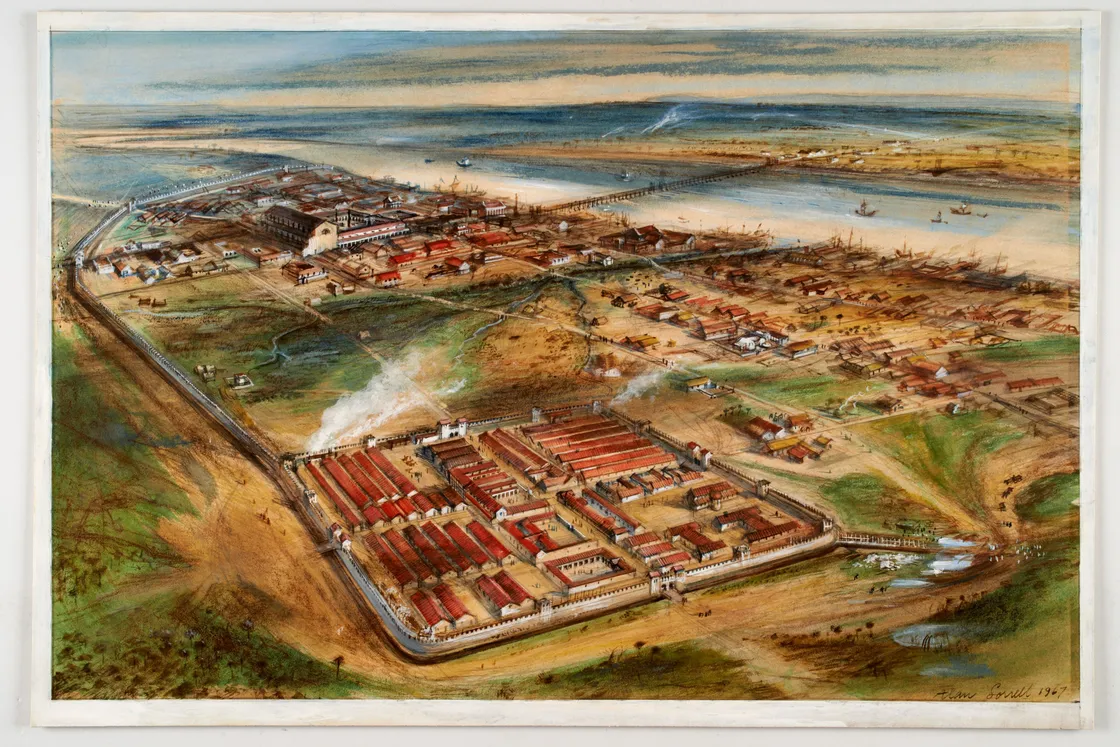

The Walbrook was a key feature of life in Roman Londinium, founded around 47 CE. It ran through the middle of the city, with the River Fleet carving out its western edge. The river was a valuable source of power for industries such as metal working and milling. And it was an important transport link, large enough in the early years of the settlement for boats to sail into its tidal inlet.

Alan Sorrell paints Roman Londinium with the Walbrook stream running through the middle.

Public baths have been discovered near the course of the stream. But the industries along the edge of the river polluted the water. And the Romans also liked to chuck their waste into it. This began the Walbrook’s use as a sewer for the past two thousands years.

Sacred waters

The Romans considered rivers to be sacred and linked to the gods. Religious objects like Venus figurines have been found in the riverbed. And curiously, so have a number of deliberately bent stylii, which were used to write on wax tablets. These could have been destroyed and thrown into the river as offerings to the gods.

Temples and shrines were built along the Walbrook’s banks. The Temple of Mithras, dedicated to the mysterious bull-slaying deity Mithras, was built there around 240 CE. The waterlogged land around the Walbrook helped to preserve the site before it was discovered in 1954. Many objects from the temple are in our collection, including altars, statues and a marble head of Mithras.

The heart of medieval London

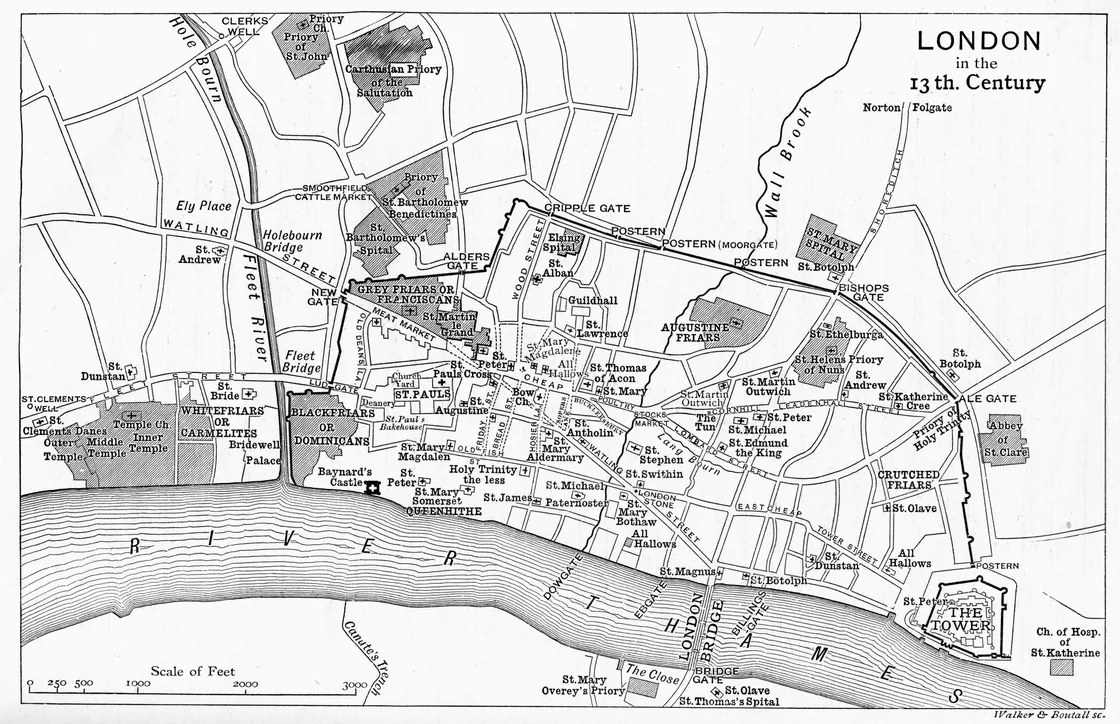

The Walbrook continued to fuel London’s industry and commerce. It powered mills, tanneries and leatherworks. Craftspeople set up their shops along the river. And a number of churches and livery halls were built along the stream.

The river began to disappear as London grew over the next centuries. But it was still an important landmark in the medieval city, used to divide the city in half, with each half then further divided into wards.

Buried underground

Despite the river’s importance, medieval Londoners decided to bury the Walbrook. The Church of St Margaret Lothbury was built over the upper part of the stream in 1440.

“The Walbrook was still pretty filthy, full of rubbish and sewage”

Around that time, the lord mayor also ordered the lower section to be covered over. The Walbrook was still pretty filthy, full of rubbish and sewage. Maybe he and other Londoners had had enough of its nasty smell.

Over the next 100 years, the river was channelled underground into tunnels. By 1600, it had completely disappeared.

Map of London in the 13th century.

Rich archaeological discoveries

Objects unearthed from the streambed give us a glimpse into what life was like around the Walbrook. This set of a nail cleaner and tweezers, for example, indicate how important cleanliness was to Roman Londoners.

Mysteriously, 39 Roman skulls were unearthed by archaeologists in the upper part of the valley. Were they gladiators? Criminals? Victims of the Roman military? It’s thought they washed out of adjacent cemeteries. We don’t know for sure. The Walbrook still holds many mysteries.