Lost rivers: The Tyburn

The River Tyburn was once a key supply of drinking water. But it fell victim to London’s expanding suburbs – and their growing sewage problem – in the 19th century.

City of Westminster

Water from the Tyburn helped to create Regent’s Park Boating Lake in the early 1800s.

Shaping London’s wealthy West End

The River Tyburn flows down from the Hampstead hills to the River Thames near Pimlico. It passes under some of London’s wealthiest areas: Marylebone, Westminster, even Buckingham Palace.

The word Tyburn comes from ‘teoburne’, meaning ‘boundary stream’ or ‘two streams’ in early medieval English. Before the Normans conquered England in 1066, the Tyburn formed a major boundary between estates outside the city walls. As suburbs were built up in areas like Mayfair from the late 1600s, the river continued to define boundary lines.

The Tyburn was more like a stream than a river, and it was never used for transport or to power London’s industry. Similar to the nearby River Westbourne, the Tyburn was used for clean drinking water before being subsumed into the sewer system in the 1800s.

“Would you drink from London’s rivers?”

Quench your thirst from the Tyburn

Would you drink from London’s rivers? It’s hard to imagine given the scale of pollution today. But only a few hundred years ago, the Tyburn was one of the rivers providing fresh water to the city.

The Tyburn sprung from two sources in the Hampstead hills. One of these springs, named Shepherd’s Well, provided clean water for the nearby Hampstead village. People also sold the water by the bucketload.

In the mid-1200s, the City of London had the revolutionary idea of building a channel to take water from the Tyburn, near where it crossed modern-day Oxford Street, to residents further into the city. Named the Great Conduit, the water supplied London’s growing population as far as Cheapside – about an hour’s walk east if you made that journey today. It was destroyed in 1666 by the Great Fire of London.

A procession passes a large monument topped with a cross in Cheapside, London, with the conduit just to the right.

Squeaky clean until the 1800s

The Tyburn remained a clear stream through Regent’s Park and to the New Road, now Marylebone Road, into the 19th century. Other rivers like the Fleet were choked up with rubbish and sewage by this point.

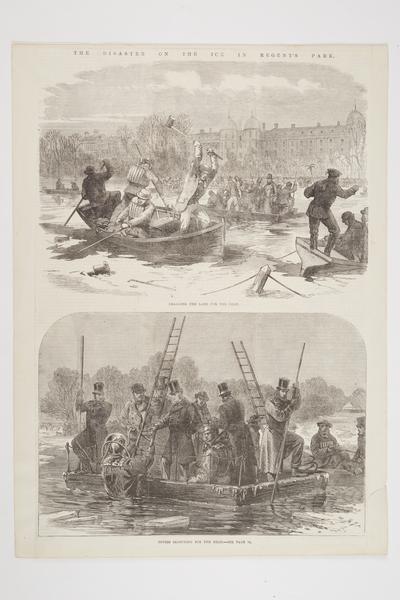

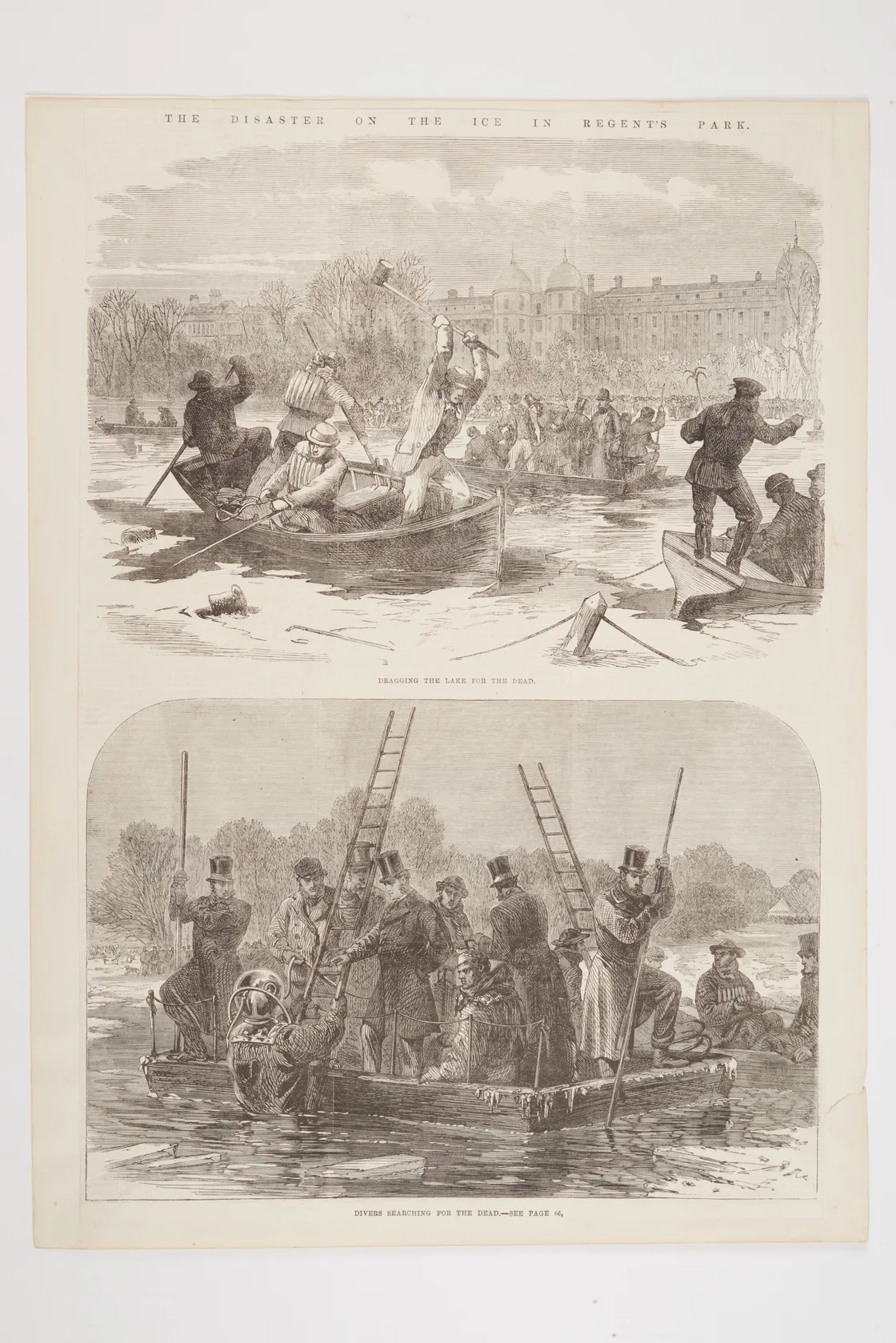

In the early 1800s, Regent’s Park Boating Lake was created using water from the Tyburn and possibly a second stream. You might notice it’s quite shallow. In 1867, people skating on the frozen lake were suddenly plunged into the icy water. Forty people drowned. The lake bed was raised so this tragedy would never happen again.

Two illustrations of the disaster on the ice in Regent's Park showing people searching for the dead.

Covered up into the 19th century

By 1670, the lower reaches of the Tyburn had been diverted into the King’s Scholars’ Pond Sewer. This was initially used for surface water drainage before it was used for sewage.

The development of Mayfair in the 1700s buried sections of the Tyburn. More of it disappeared as the city grew northwards. By the 1830s it was already underground up to Primrose Hill. Then as Hampstead developed from a meadowy village to a suburb, it was fully underground.

In the 1860s, the Tyburn was turned into a waste sewer, flowing between Hampstead and Westminster.

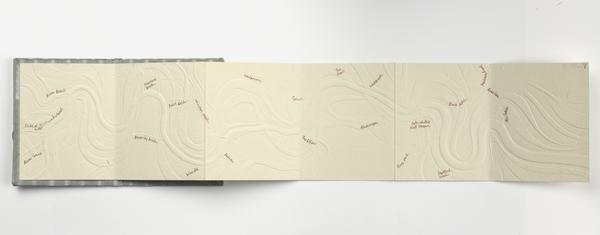

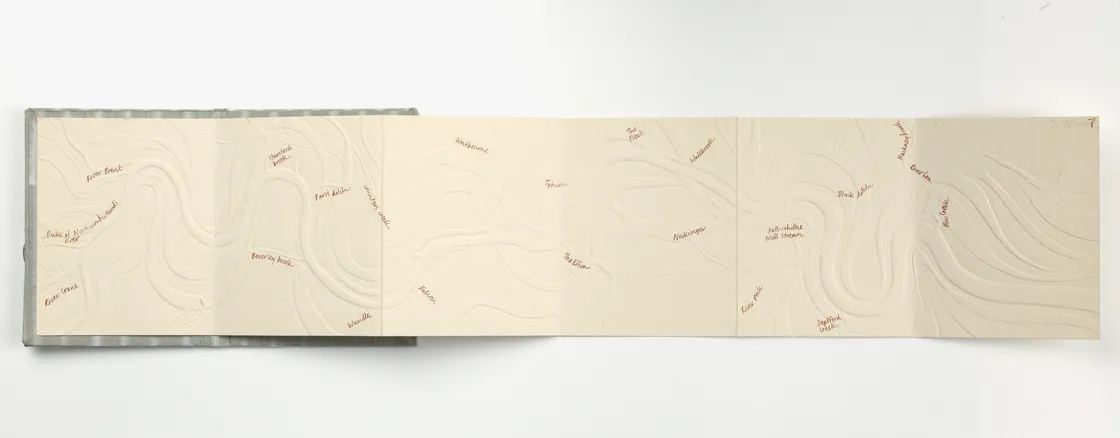

One of artist Tracey Bush's books based on the River Thames which traces London's lost rivers.

The campaign to bring the Tyburn back

The Tyburn may have long disappeared, but for some Londoners, it hasn’t been forgotten.

The Tyburn Angling Society, who claim to have been founded by royal decree way back in 959 CE, have campaigned for the restoration of the river since the 1990s. They want to bring it back up to the surface so it can become a habitat for trout and salmon.

To do so, the buildings earmarked for demolition would include some of the city’s most expensive properties – including Buckingham Palace. It might seem like a pipe dream. But you could see the benefits of London’s watery heritage brought back for us all to enjoy.