Lost rivers: The Fleet

London’s largest hidden river, the Fleet was vital to Roman and medieval life and industry. But it also became one of the city’s stinkiest open-air sewers.

Camden

Fetid, filthy and full of dead dogs

Flowing from Hampstead and Highgate down to Blackfriars Bridge, the Fleet had a long and colourful history before it was buried underground.

It provided routes for trade. And it sustained daily life for Londoners as a source of food, drinking water and bathing water.

But as London’s population expanded, it became widely used as a place to dump rubbish, sewage and other nasty things. You wouldn’t want to take a dip in parts of the Fleet.

A key part of Roman industry

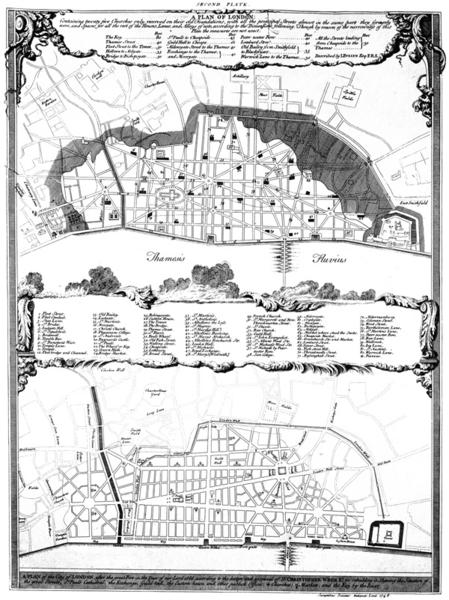

The Fleet formed the western boundary of the Roman settlement of Londinium, with the River Walbrook running through the middle of the city.

The Romans built the first bridge over the Fleet. This thoroughfare – Fleet Street – is still in use today.

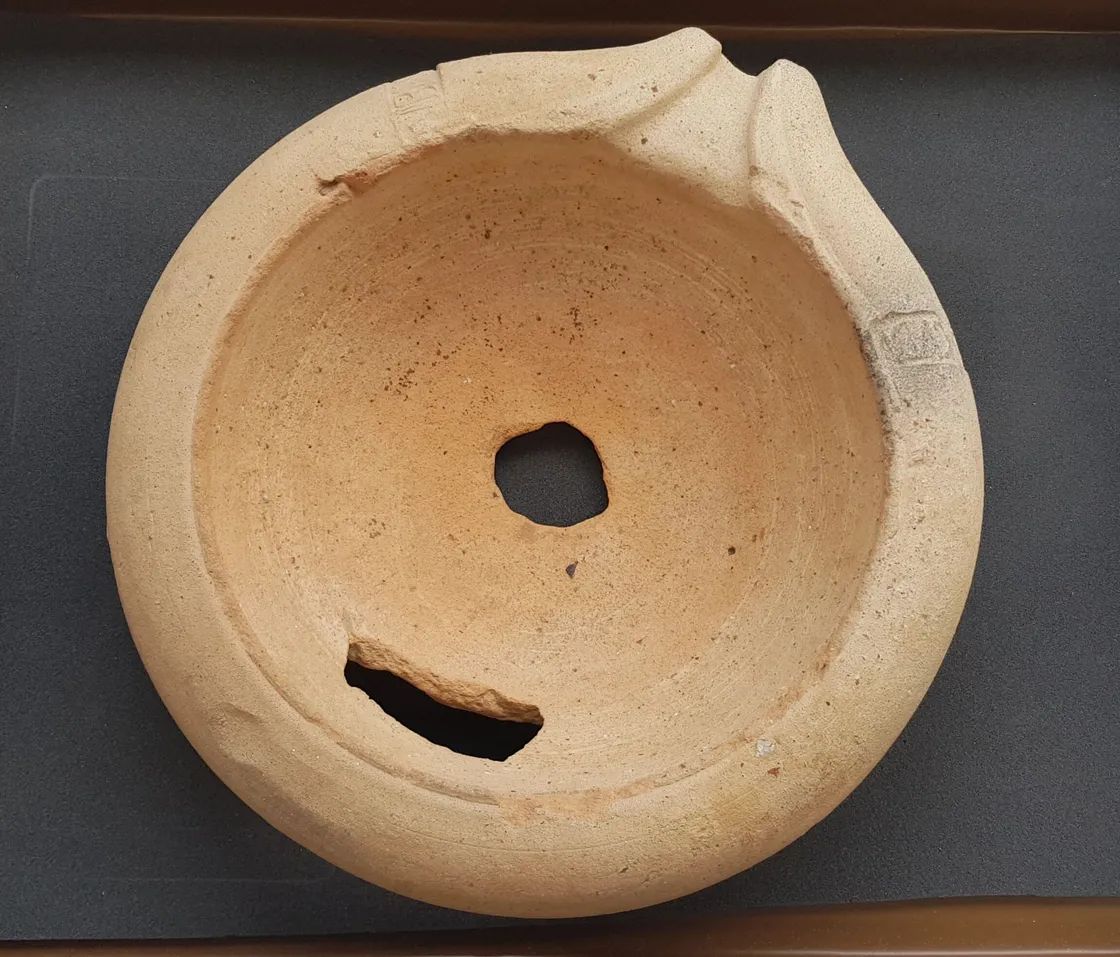

And the lower section of the river was tidal and wide enough for ships to sail up and unload goods. This mortarium (used to grind food and herbs) was excavated from the Fleet Valley and might have been brought in on this cargo route.

Mortarium from the 1st century CE.

The Fleet’s water continued to power industrial activity into the post-medieval period, such as snuff mills, liquorice mills, tanneries and breweries. From the late 1400s to the 1600s, the Fleet Valley, which stretched from Clerkenwell to the Thames, was a metalworking centre.

“The river became a cocktail of waste: industrial, human and even animal”

The Fleet’s great stink

As London’s population increased, the Fleet essentially became an open-air sewer. Londoners had reckoned with its mighty stench since at least the 1200s, when the monks of Whitefriars complained to the king about its “putrid exhalations”.

The river became a cocktail of waste: industrial, human and even animal. The Smithfield butchers chucked carcasses from their nearby meat market into the river.

The notorious Fleet Valley

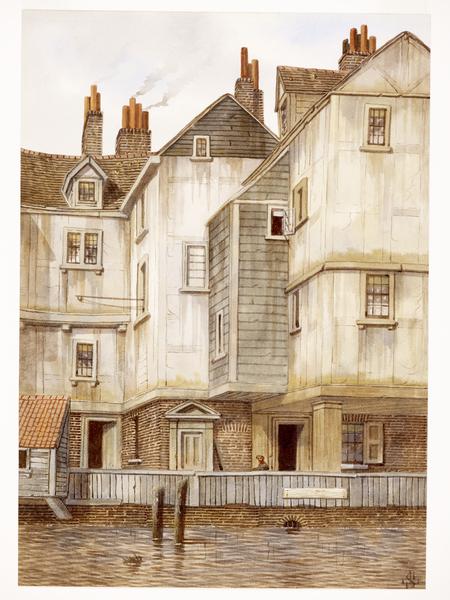

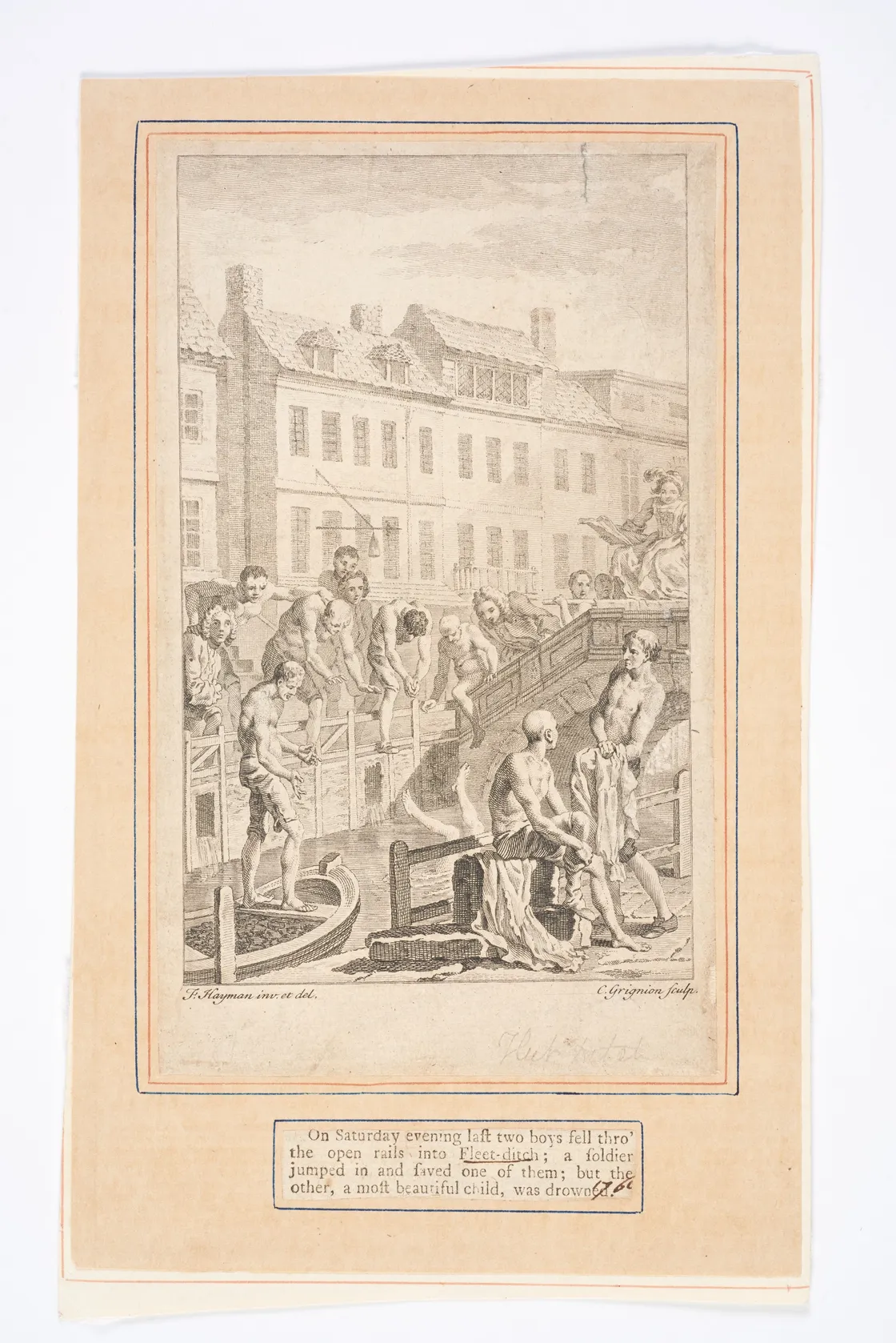

The Fleet Valley had many slum areas where Londoners lived in poor-quality housing. This lower section of the river was known as the Fleet Ditch. It had become so silted and filled with rubbish that it was more of a ditch than a river.

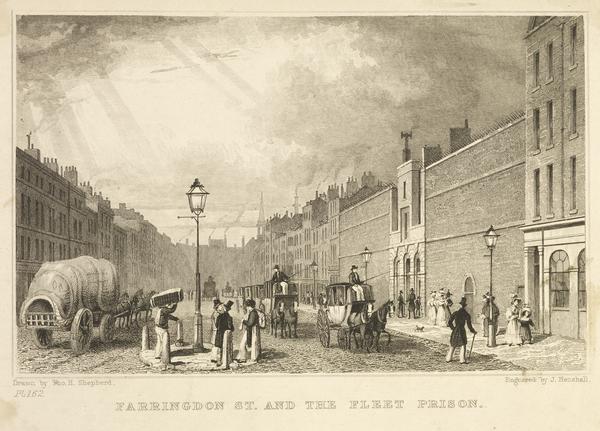

The cheap surrounding land also made it a popular spot for building prisons. Fleet Prison, a debtor’s prison, was built on a small island within the river in 1197. As the river filled up with silt, it gradually became part of its east bank, where it stood until 1846. The similarly notorious Newgate Prison was situated nearby.

The area’s reputation for danger and disease lasted into the 19th century. In his novel Oliver Twist, Charles Dickens set Fagin’s lair in the nearby Saffron Hill area. He described it as the dirtiest and most wretched place “where drunken men and women were positively wallowing in the filth”.

Christopher Wren attempts to clean up the Fleet

There were unsuccessful efforts to clean up the rubbish in the river in the 1500s and 1600s. After the Great Fire of London in 1666, architect Christopher Wren turned the lower part of the Fleet into a canal.

“Drown’d puppies, stinking sprats, all drench’d in mud”

Jonathan Swift, 1710

But the pollution was relentless. Author Jonathan Swift vividly described it in 1710 as full of “Sweeping from butchers’ stalls, dung, guts and blood, Drown’d puppies, stinking sprats, all drench’d in mud.” Yes, the Fleet was even known for being polluted with dead dogs.

Men bathing in Fleet Ditch.

After just 50 years, the Fleet had become so choked up with waste that Wren’s unpopular canal was gradually covered over from 1733.

The River of Wells

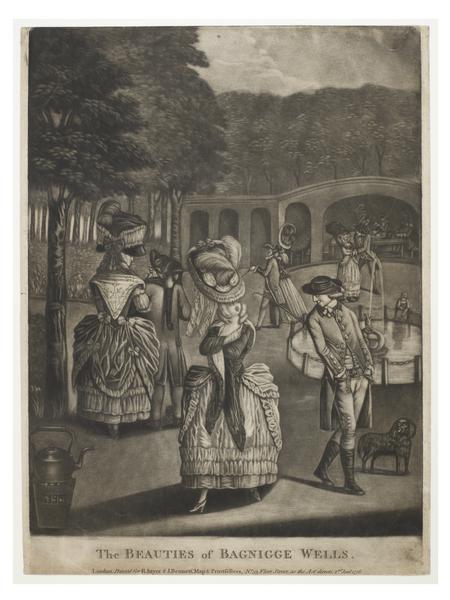

The history of the Fleet isn’t all grubby, though. It was also known as the River of Wells because of the wells that had been built along its banks since the 11th century. Many were thought to have healing qualities.

In the 1700s, popular wells upstream near King’s Cross, such as St Chad’s Well and Bagnigge Wells, were turned into fashionable spas. Londoners paid to visit these gardens to socialise, enjoy the springs and play games. Both closed by the mid-1800s.

People promenade around the Bagnigge Wells fountain.

Buried underground

After the Great Stink of 1858, caused by waste in the Thames, part of the Fleet was incorporated into new sewage tunnels designed by engineer Joseph Bazalgette. The development of the Regent’s Canal (from 1812) and the Metropolitan railway line (in 1862) led to more sections being pushed underground.

Today, the Fleet is fully underground and largely part of our sewer system. But you can technically still swim in the Fleet today by taking a dip in Hampstead Ponds on Hampstead Heath, as these feed the river at its source.