London’s whaling trade: Blubber & baleen

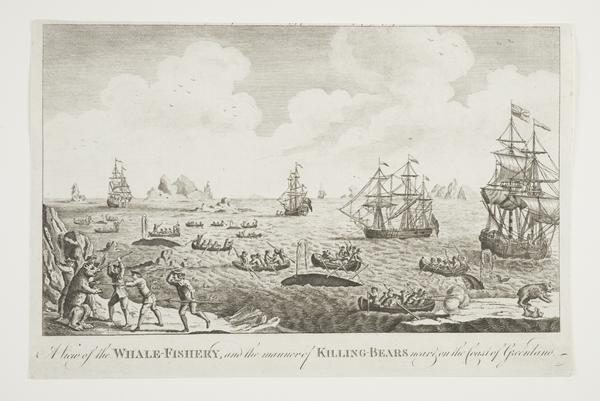

London’s docks were once the centre of a busy whaling trade. Ships hunted the Arctic and the South Seas, harvesting whale oil and whalebone for an incredible range of uses.

Greenland Dock

1611–1859

Blood, blubber and bone

In January 2006, a bottlenose whale swam up the River Thames into central London. The whale was dubbed Willy by the media, and won the love of Londoners. A rescue was attempted, but the whale sadly died.

Two hundred years earlier, the city showed much less affection for whales. From the 1600s to 1800s, ships sailed from London to hunt whales for their valuable blubber and whalebone, trading these products in the city once they returned.

A woman walking through London in the 1750s might have proudly worn a whalebone corset, and lit her home with a whale-oil lamp.

It’s an elegant scene – but there’s violence behind it. Hunting whales was, and still is, a bloody, drawn-out ordeal. Since 1986, the International Whaling Commission – which includes the UK as a member – has banned commercial whaling, though it continues in some countries.

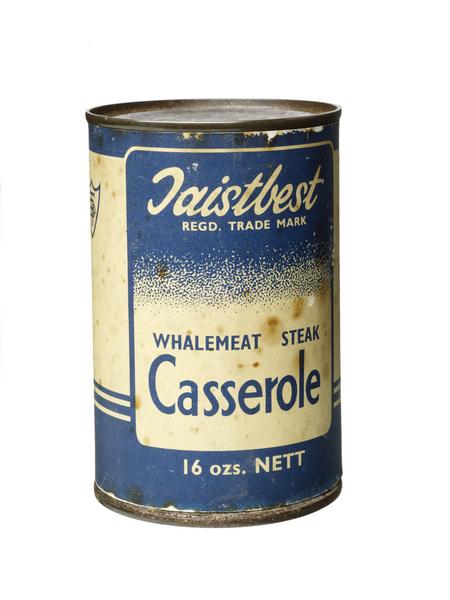

What were whales used for?

After being harpooned at sea, whales were hauled to the ship and killed. They were then taken apart to extract only the most valuable parts of the animal.

The main target was whale fat, called blubber. When boiled, blubber produced oil which could be used in soap or paint, applied as a lubricant, or burned to light homes.

Whalers also removed the animals’ jawbones and drained the oil inside. The bones were sometimes used in the framework of garden sheds or as ornamental gateposts.

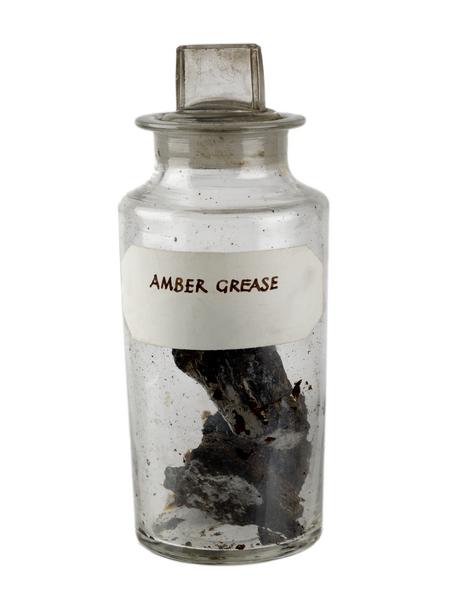

Oil from sperm whales was especially valuable because it burned without colour or smell. Spermaceti wax, taken from a chamber in their head, was used to make top-of-the-range candles. Ambergris, from the stomach, was used in perfume.

By the late 19th century, baleen was more valuable than oil. Baleen, also called whalebone, is found in the mouth of the North Atlantic right whale. The plates of baleen act as a filter, trapping the sea creatures that the whales eat.

This strong and springy material was used in a similar way to plastic. Specialist London whalebone cutters prepared it for all sorts, including corsets, fishing rods, carriage springs and umbrellas. Baleen was also artfully engraved by sailors, making something known as ‘scrimshaw’.

Occasionally, we find whale bones that have been used in more unusual ways. As well as whalebone corsets, our collection includes a bone spear for hunting birds and a piece of bone used to repair a whaling ship. Both were found on the Thames foreshore by mudlarks.

The Muscovy Company

London’s first whaling company was the Muscovy Company. Established in 1555 with a trading monopoly from Queen Elizabeth I, it launched its first whaling expedition in 1611.

They targeted the Arctic and the North Atlantic right whale. It didn’t go well. The company lacked expertise and faced violent competition from Dutch whaling ships.

The Muscovy Company folded in 1619 and was replaced by the Greenland Company. More failures followed and the London trade practically died out between 1650 and the start of the 1700s.

The start of South Sea whaling

London’s Arctic whaling rebounded in the 1700s, in part thanks to a government bonus for whalers and the increasing demand for baleen. It peaked in the 1780s.

From 1775, London whaling ships began to scour warmer waters for sperm whales.

So-called South Sea whaling began with voyages to the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, but from 1800 spread to cover the whole of the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Whale populations soon dwindled, meaning that expeditions sometimes took years to gather enough cargo to take back to London.

Our collection includes the log of a South Seas whaling ship. Examine the pages below and you’ll see illustrated whale tails marking every whale killed.

London docks and the whaling trade

The Arctic whaling trade in London was centred on Greenland Dock in Rotherhithe, originally built as the Great Howland Dock around 1700.

Blubber was boiled in ‘coppers’ at the dock. Baleen plates were cleaned of any rotting flesh. The boiling caused a horrendous smell. As one observer said: “it is impossible to say one word on the deliciousness of its fragrancy.”

Ships hunting the South Seas made heavy use of the City Canal, which cut across the Isle of Dogs, to unload their barrels of sperm whale oil. This canal later became part of West India Docks.

The whaling trade employed thousands of people. As well as docks for handling cargo, London had the dockyards needed for shipbuilding. It had the necessary sailmakers, carpenters, blacksmiths and coopers (who made barrels). And, as an established trading centre, London had ship owners and merchants willing to take a bet on whaling expeditions.

Whales were sometimes stranded in the Thames

Although ships sailed huge distances to find whales, historical records dating back to medieval times also tell stories of huge “fishes” becoming stranded in the River Thames.

An account from 1309 describes a ruling granting the bishop of St Paul’s the right to all whales stranded on their land – except the whales’ tongues, which went to the king.

In 1532, a Venetian ambassador described how Londoners saw the capture of two whales in the Thames as a bad omen, linking it to a spate of suicides.

In 1762, a 16-metre-long sperm whale was caught near Gravesend in Kent. It was dragged to Greenland Dock and displayed to the public. Newspapers and journals wrote about the whale, and thousands came every day to see it. “Their Journey” one source tells us, “prov’d unsavoury at the End, for the Whale stunk abominably.”

In 2010, archaeologists digging on the Thames foreshore close to the O2 Arena in Greenwich found the enormous skeleton of a North Atlantic right whale. It was probably killed sometime around 1658 and was dragged onto the foreshore, where its head was removed for the valuable baleen and oil-rich jawbone.

A harpoon that was used on board a Leith Greenland whaling ship.

How did whaling end?

London’s whaling trade disappeared in the 19th century. The last whaling ship set off in 1859.

Many factors led to the decline. The government removed financial support for the industry in the 1820s. Taxes were lowered on imports of oil from British colonies. And competition increased from Australian and American whalers.

Alternative products like coal gas, kerosene and other mineral oils removed the need for whale oil in lighting, lubrication and textile-making. Steel, and later plastic, reduced the need for baleen.

In 1986 the International Whaling Commission paused commercial whaling to prevent whales being hunted to extinction. That pause has continued, but Norway, Iceland and Japan have all caught whales commercially since.