London’s public executions

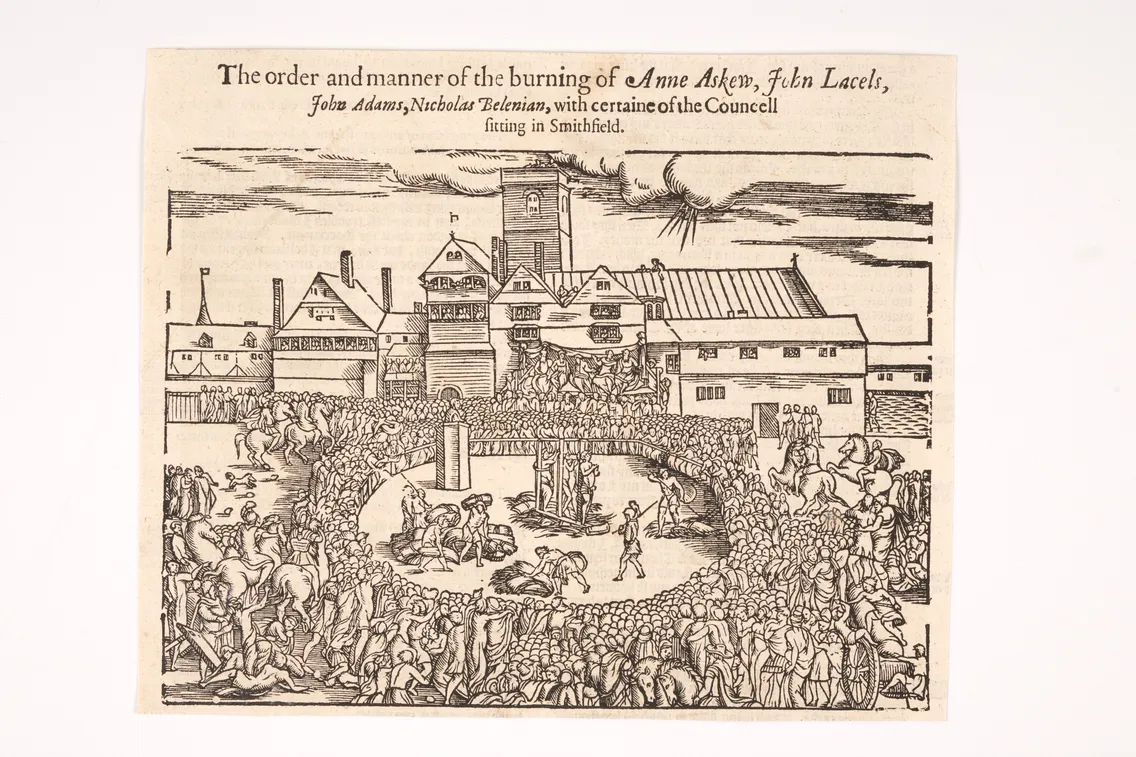

Between 1196 and 1868, tens of thousands of people were executed in public in London. Executions were a show of state power and a spectacle which became part of city life.

Across London

1196–1868

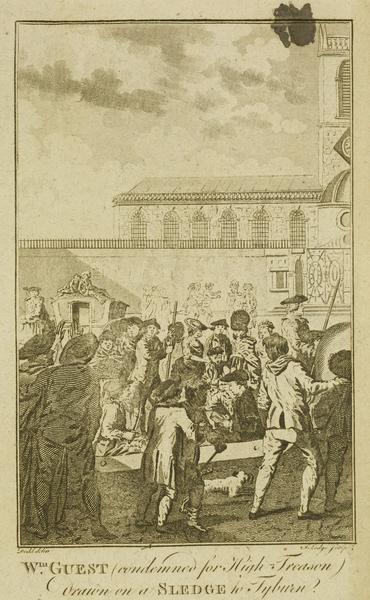

William Hogarth's engraving shows a condemned man being carted through a crowd to the Tyburn gallows.

This page contains content some people may consider sensitive, or find offensive or disturbing. Understand more about how we manage sensitive content.

A very public death

Crowds of up to 50,000 people gathered to watch executions at infamous sites like Tyburn and Newgate Prison.

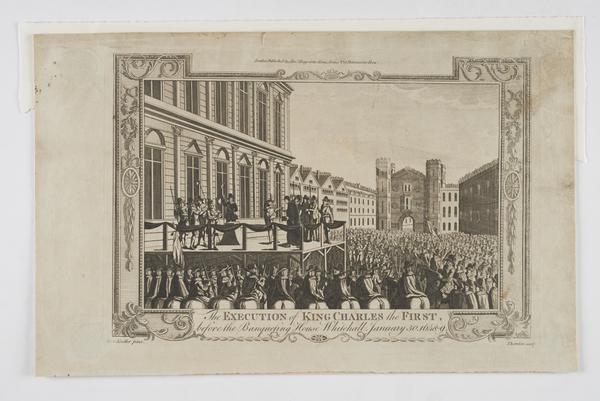

People of all classes were executed – including King Charles I – and their bodies were often displayed as a warning to others.

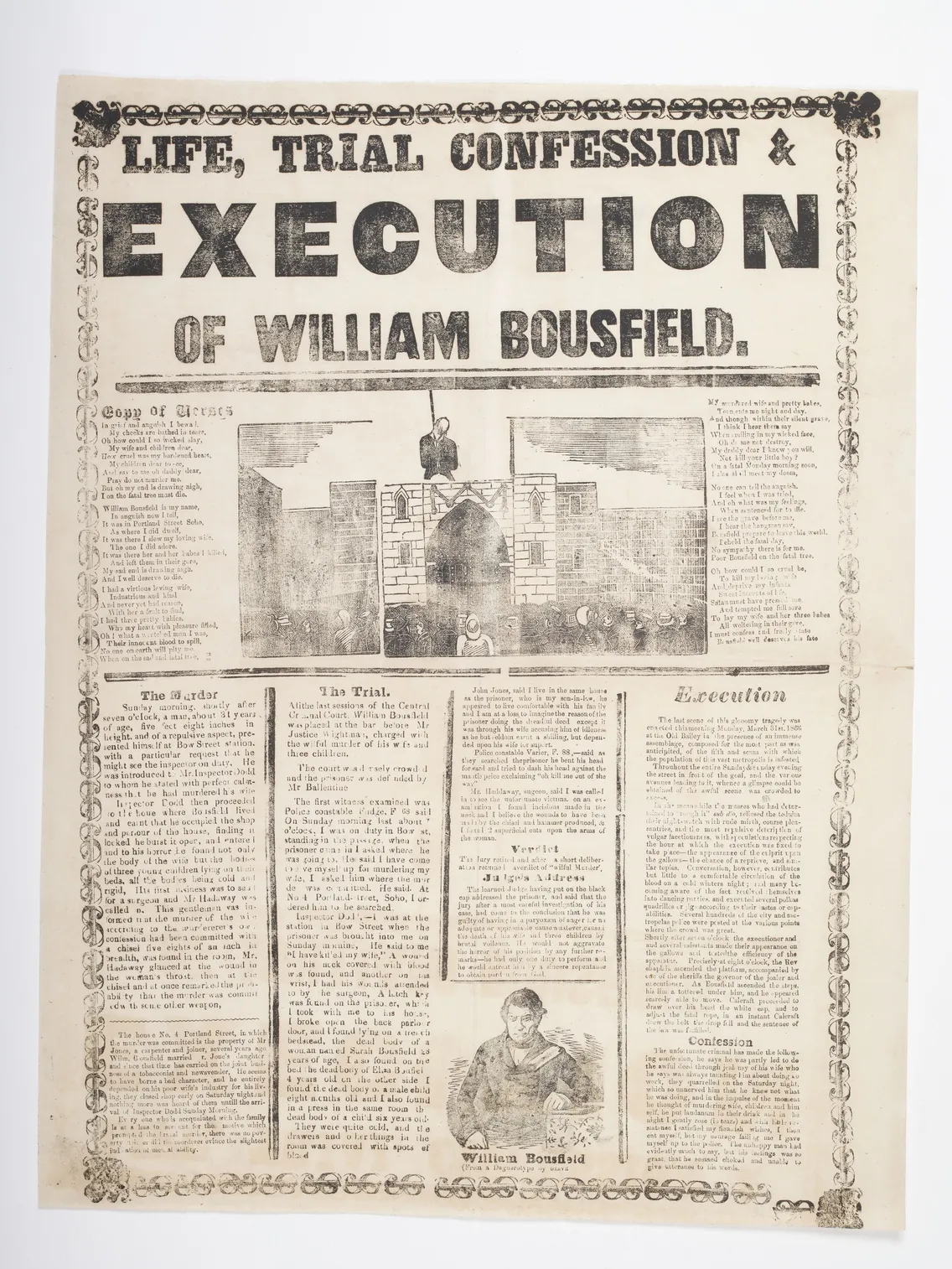

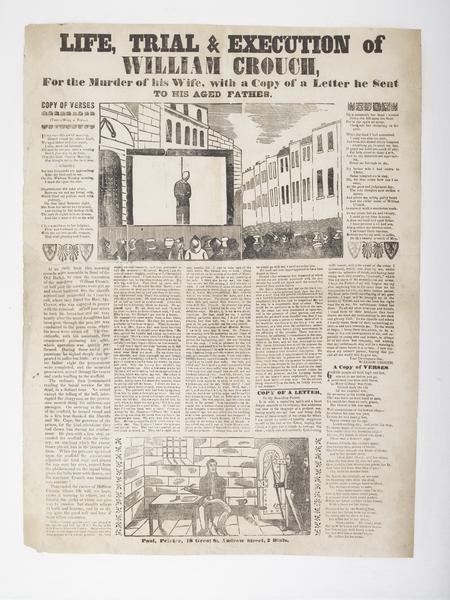

Death sentences were given for treason and murder, for burglary and forgery, and for acts which are no longer illegal. By the end of the 1700s, over 200 crimes were punishable by death.

Public executions ended in the 1860s, when people questioned whether executions were an effective way to prevent crime – and whether it was right to watch such a brutal act.

“they paraded the grisly apparatus of death through almost every quarter of London”

Charles Knight, 1841

How were people executed?

Hanging was the most common execution method. But punishments took a variety of grisly forms at different times.

Until 1726, women were burned at the stake for murdering their husbands. In the 16th century, Henry VIII boiled people as punishment for poisoning.

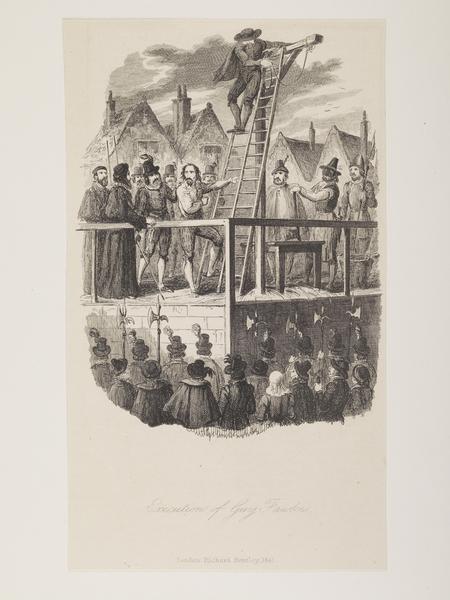

Drawing, hanging and quartering was the most gruesome and complicated. The person was dragged behind a horse, hanged until almost dead, then had their intestines removed, and their head and limbs cut off. This punishment for traitors, including Guy Fawkes, began in the 12th century and continued in some form until the 19th century.

Members of the nobility could be beheaded instead, sometimes in private – a method seen as relatively quick and kind. One of the more fearsome items in our collection is an executioner’s axe, intended for the ringleaders of the Cato Street conspiracy.

This axe was made for the execution of the Cato Street conspirators in 1820, but eventually a surgical knife was used instead.

Where were people executed in London?

For 600 years, from the Middle Ages until the late 18th century, Tyburn was London’s main execution site. Its infamous gallows stood in the area we now call Marble Arch.

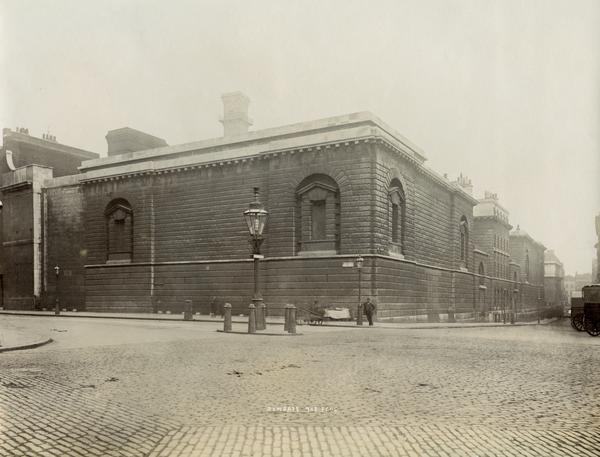

After 1783, Newgate Prison in the City of London became the main spot for executions. Smithfield, Horsemonger Lane, Execution Dock and Tower Hill were other regular locations.

The condemned were sometimes executed close to the site of their crime, as Charles Knight described in 1841: “they paraded the grisly apparatus of death through almost every quarter of London. There is scarcely a street… in which it has not planted its black foot.”

A ceremony like no other

Tyburn executions took place eight times a year, making them a much-anticipated occasion. They were full of ceremony, involving City and religious officials.

The process started at midnight the night before, when a bell at the nearby St Sepulchre church was rung.

Before leaving their cells, prisoners traditionally penned a final letter or inscribed tokens with a message. In 1826, George Wright left his mark on a metal token: “In my dismal cell I lie, in sorrow grief and woe, For my time it seems so long, my doom I wish to know.”

The prisoners were carried the 4.5km to the gallows in sledges or open carts, with large crowds following the procession.

Although executions were meant to show that the authorities were in control, the reality was often chaos. There were attempted rescues, botched hangings, last-minute pardons and crowd crushes.

“the multitude became hardened and literally acquired a taste for blood”

Thomas Hobhouse, 1866

Executions as entertainment

All sorts of people watched. The 18th-century lawyer James Boswell described the “irresistible impulse to be present at every execution”.

The crowds cheered the execution of people cast as villains, and supported folk heroes like Jack Sheppard, who was executed after becoming famous for his prison escapes.

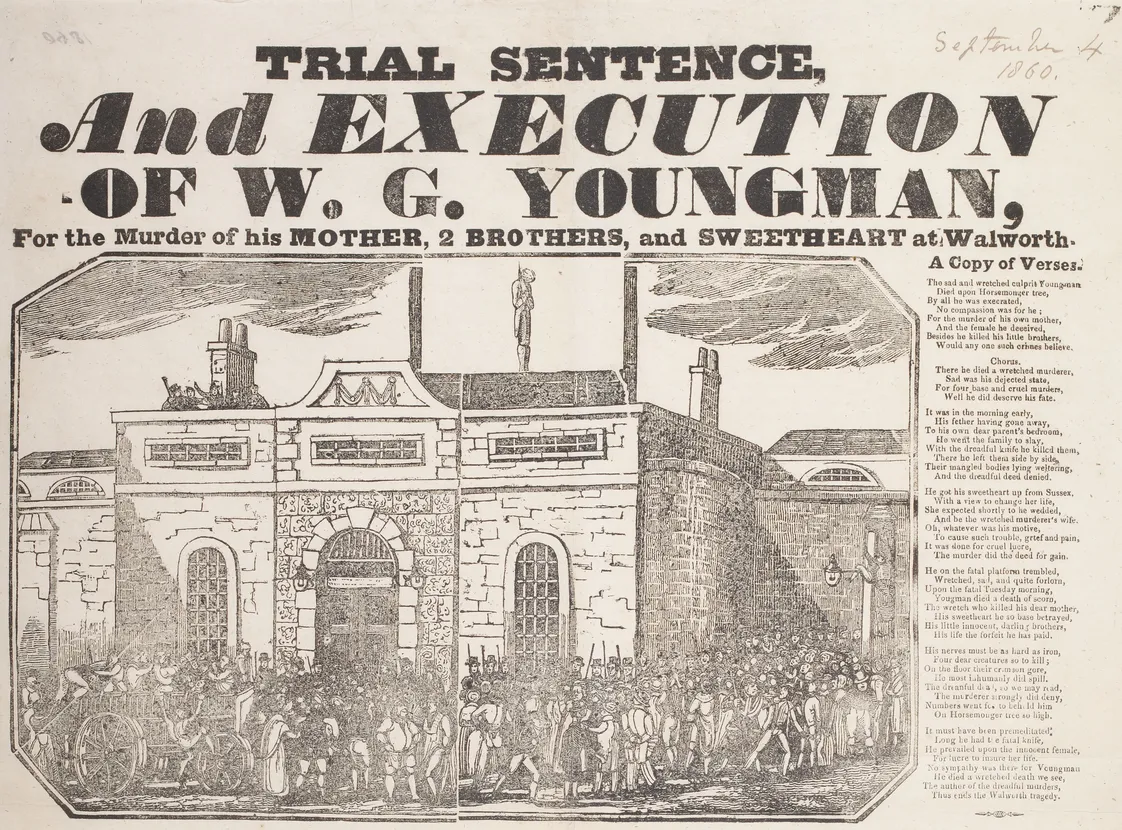

With the crowds came opportunities to make money. Spectators paid for the view from nearby windows or grandstands. Street sellers sold food, drink and printed ballads claiming to report the last words of the condemned.

You can picture the scene with the help of the 1805 work from our collection by Thomas Rowlandson. His drawing of a rowdy crowd outside Newgate Prison is exaggerated for laughs, but it shows us that these weren’t always sombre occasions.

After the execution: display and dissection

Up until the 17th century, the heads of traitors – William Wallace included – were displayed on London Bridge as a warning to others.

London’s city gates were used for this purpose too, while the bodies of murderers, highway robbers and pirates were hung in gibbet cages by main roads, on commons or by the Thames.

From the mid-16th century up until 1832, the bodies of the executed were also used for medical research and dissection.

Gibbets like these were used to display the bodies of people who'd been executed.

An end to executions

By the 1860s, there were new ambitions to make London a more civilised place.

Campaigners pressed politicians to end public executions – not out of sympathy for the condemned, but because they thought watching such a violent act was uncivilised.

The MP Thomas Hobhouse gave his thoughts on the execution crowd in 1866: “The feeling that obtained there was not one of horror, not one of fear, but a feeling by which the multitude became hardened and literally acquired a taste for blood.”

Transporting convicts to British colonies offered an alternative punishment. And the Metropolitan Police Service was formed in 1829, giving the authorities a new way to prevent crime.

Public executions were abolished in 1868, but death sentences were still carried out inside prisons. 335 people were executed inside London prisons between 1868 and 1961.

The death penalty for murder in England, Wales and Scotland was abolished in 1969.