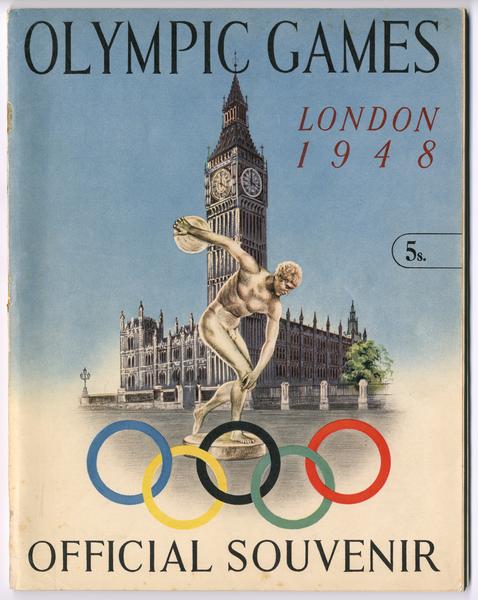

London 1948 Olympics: The ‘Austerity Games’

The 1948 Olympics were a far more frugal version of the Games compared to today. But they injected some colour into a gloomy and war-weary Britain.

Across London

29 July – 14 August 1948

A make-do-and-mend Olympics

Summer 1948. Barely three years since the end of the Second World War. London was still scarred by bombing. People were living on rations. And yet the city buzzed as it hosted the first Olympics since the 1936 Games in Adolf Hitler’s Berlin.

Pulled together on a tight budget in just two years, these summer Olympics have been retrospectively called the ‘Austerity Games’. Organisers used venues that already existed around London. Even the athletes' food was rationed. But perhaps against the odds, it was celebrated as a harmonious success and said to represent a sense of healing from war.

An austere summer Games

The 1948 Games were pretty pared-back for both the participants and the spectators. Compared to the many temporary and permanent venues built for the London 2012 Olympics, these Games used the city’s existing infrastructure.

The main athletics events were held at Wembley Stadium, where a temporary running track had been laid. Other events took place in existing venues, such as cycling at Herne Hill Velodrome and basketball and wrestling at Harringay Arena.

There also wasn’t a purpose-built Olympic village for the athletes. They stayed in schools, hostels and even converted old wartime barracks in Richmond Park. London-based British athletes commuted from home.

This brushed aluminium Olympic torch was made in the EMI factory in Hayes.

The opening ceremony’s message of hope

The Games began on 29 July. The Olympic torch had been carried across war-torn Europe, from Greece to the opening ceremony at Wembley Stadium. One of the 1,720 torches made to carry the Olympic flame is in the museum’s collection.

“Everything is noise and colour now”

Sunday Mirror, 1948

King George VI presided over the ceremony attended by more than 80,000 spectators. Seven thousand doves were released, sending a message of culture and peace across the globe. “Everything is noise and colour now,” wrote a Sunday Mirror journalist of the occasion.

The city hosted 4,099 contestants from 59 nations – around double the athletes of the first London Olympics in 1908. But the dark shadow of the war was still present. Germany and Japan were excluded from the Games and the Soviet Union decided to abstain.

Who had sporting success?

One of the stars of 1948 was 30-year-old Dutch athlete Fanny Blankers-Koen. She was the first woman to win four gold medals at a single Olympics. And her dominance in track and field challenged prejudices about gender, motherhood and age in sport.

Fanny Blankers Koen crosses the finish line in 11.9 seconds to win the Women's 100 meter race.

The USA came top of the table with 84 medals. In the high jump, the African American Alice Coachman became the first woman of colour to win an Olympic gold.

Britain, with their 27 medals, came 12th in the medal table. One of their four golds went to Alfred Thomson – for his painting of boxers at the London Amateur Boxing Championships. Yes, from 1912 to 1948, medals were awarded for Olympic arts too.

A broadcasting triumph by the BBC

Despite the frugal conditions, the Games also saw some technological innovations, including starting blocks for sprint races. This was also the first Olympics to be broadcast by the BBC on television. But few people owned televisions in 1948, so most continued to rely on radio for news of the games.

It was the most challenging and complex major event the BBC had ever televised. Pulling it off took a year of planning and sourcing the latest technology for outside broadcasting

“The greatest feat of sports organisation ever attempted in Britain”

Guardian, 1948

Overall, the games proved popular with Londoners. Many people welcomed the chance to focus on an event that restored a spirit of international harmony. When the Games came to a close on 14 August, it was reported as a total triumph.

“The Games have been a resounding success,” wrote the Guardian, “the reward of the greatest feat of sports organisation ever attempted in Britain.”