Limehouse: London’s first Chinatown

Before Chinese restaurants, businesses and communities laid down roots in the West End, London’s first Chinatown could be found on the other side of the city.

Tower Hamlets

1800s & early 1900s

Looking back at London’s lost Chinatown

Limehouse in Tower Hamlets is an area shaped by the curve of the River Thames and the history of its ports and docks.

In the late 18th century, Chinese sailors began working here for British shipping companies. They’d often stay in the Docklands until they could find work on another ship that would take them home.

Around 100 years later, Chinese communities and businesses had settled in the area. London’s first Chinatown was born.

Today, little remains of the Limehouse Chinatown. But you can still see glimpses of its history in the area’s street names such as Ming Street, Pekin Street and Canton Street.

How Chinese sailors came to London

From the late 1700s, Chinese seamen were brought to Britain to load and unload ships in London’s docks and other ports across the country. They were recruited by the East India Company, a powerful and exploitative imperial trading corporation, and other British shipping companies.

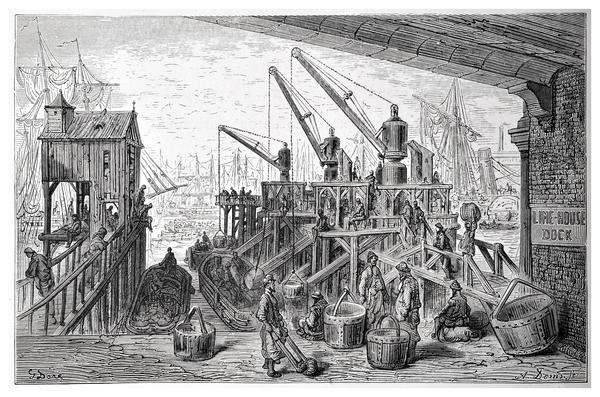

French artist Gustave Doré illustrates Limehouse dock for a book called London: A Pilgrimage, published in 1872.

British imperial influence and ambitions in China increased over the course of the century. And the importation of goods and raw materials from Asia resulted in a larger number of Chinese seamen arriving in London. British shipping companies paid Chinese sailors less than half the wage of a British seaman or labourer.

These sailors would stay in the local lodging houses or public houses in between jobs. Some decided to permanently live in east London. Many of this mostly-male settled Chinese population married local women and had children.

A new life in Limehouse

Chinese communities settled in two parts of Limehouse. People from Shanghai lived in Pennyfields, Amoy Place and Ming Street. And those from southern China lived in Limehouse Causeway and Gill Street. The area had a lot of poverty and overcrowding. Residents rented rooms in terraced houses of multiple occupants, squeezed among the factories and dockyards.

In the 1880s, a small number of enterprising Chinese migrants established businesses like restaurants, laundries, hostels and grocery stores that provided travelling seamen with familiar home comforts.

But many other Londoners also began to venture into Chinese restaurants and, more controversially, Chinese-run opium dens.

Chinese women arrived later in the 1920s, with many employed as ‘amahs’ doing household tasks for English families.

Facing hostility and the Limehouse myths

Like other migrant communities in London, Chinese people faced racism and hostility. Limehouse in particular was turned into the focal point of sensationalised anxieties around Chinese migration to Britain, fuelling the social exclusion of the Chinese communities there.

Myths of the area as a hotbed for gambling, opium smoking, danger and sexual abuse were peddled by politicians and the press. Limehouse Chinatown was also dramatised in novels like Thomas Burke’s Limehouse Nights (1916) and Sax Rohmer’s racist, and at the time hugely successful, series of books about a Chinese criminal named Fu Manchu.

The idea of opium dens as places of ‘exotic’ danger and pleasure was also endlessly repeated in the press and in popular culture.

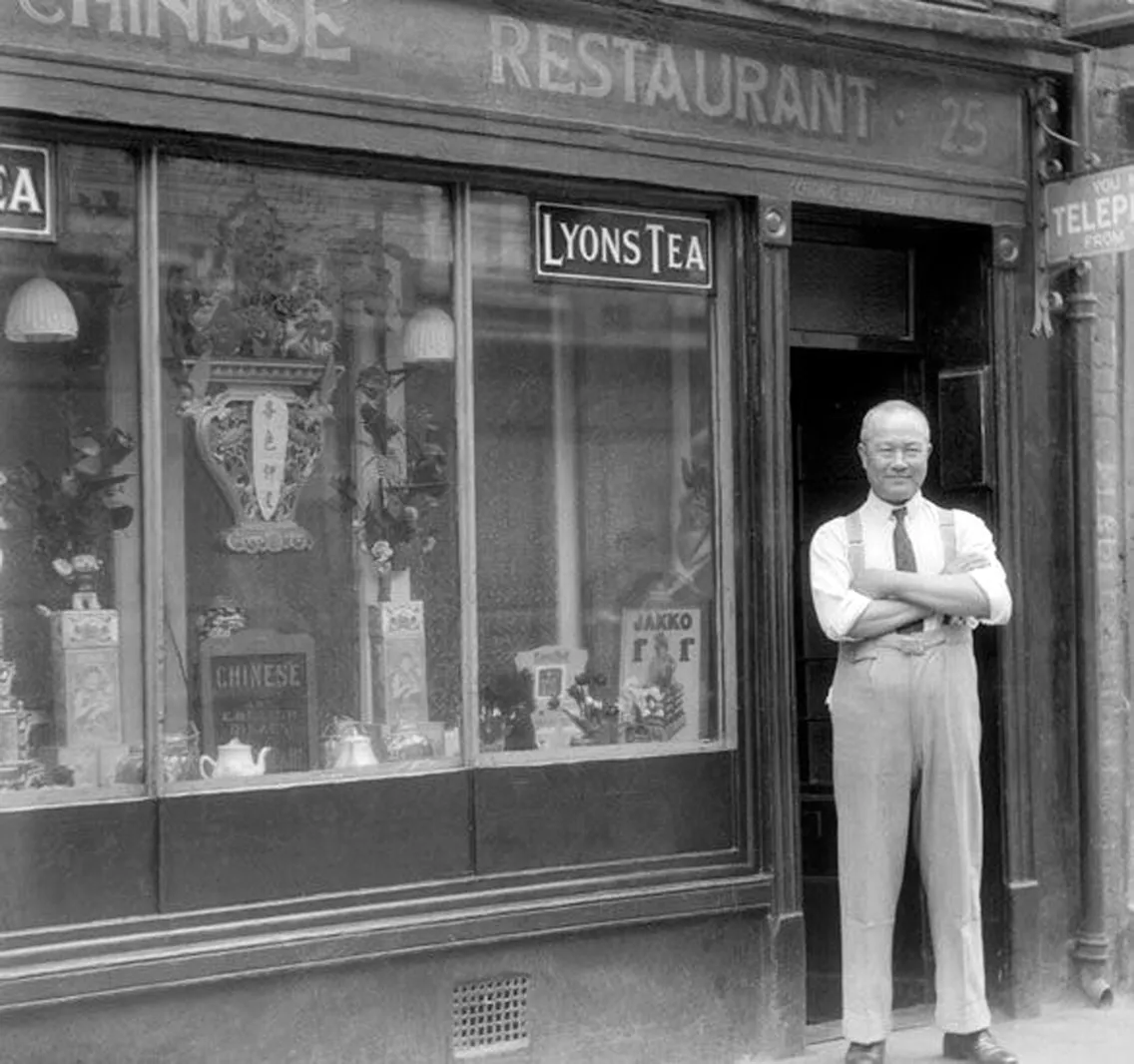

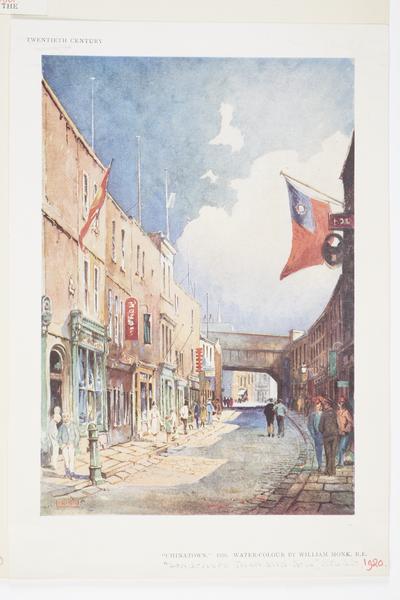

Chinese businesses on a street in Limehouse.

Limehouse had been constructed as a place so infamous that in the 1920s, travel agents Thomas Cook & Son organised bus tours to the area.

But Chinese communities were one of many different nationalities that called the area home. And only around 300 Chinese people were living there as permanent residents at Chinatown's peak in the 1930s.

The celebrated Chinese novelist Lao She reflected on this hysteria in his London-based 1929 novel Mr Ma and Son: “If there were no more than twenty Chinese people dwelling in Chinatown, the accounts of the sensation-seekers would without fail magnify their number to five thousand. And every one of those five thousand yellow-faced demons will smoke opium, smuggle arms, commit murder…”

“Although Limehouse was a poor area, it was also full of warm community spirit”

Connie Hoe

The East End Chinatown community

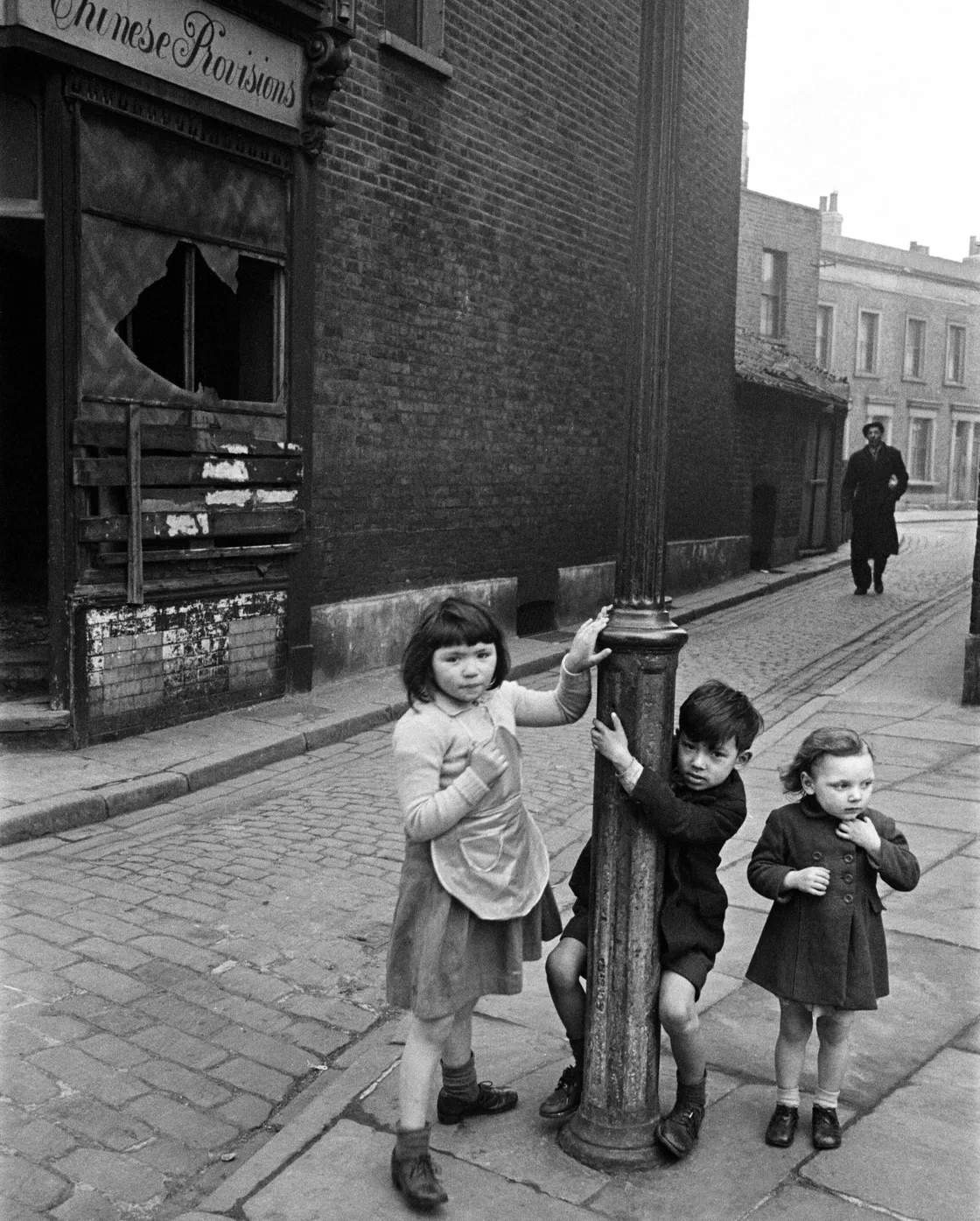

Connie Hoe, who was born in Limehouse to a Chinese father and English mother in 1922, remembers that “although Limehouse was a poor area, it was also full of warm community spirit. Us children used to play in the street and if your friend was called in for dinner you just sat down at the table and ate with them.”

Children in Chinatown.

Community organisations and schools were set up to help Chinese people adapt to life in London while also staying connected to their culture. In 1934, a Chinese school named the Chung Hwa Club opened on Pennyfields providing Chinese culture and language classes to children of Chinese heritage in the East End. Spaces like these helped create a sense of safety and security away from the racism that many Chinese people faced.

What happened to Limehouse’s Chinatown?

Limehouse’s Chinatown began to decline in the 1930s, a decade marked by a long and severe economic downturn worldwide. This economic depression caused a decline in Britain’s shipping industry, leading numerous Chinese migrants to go back to China.

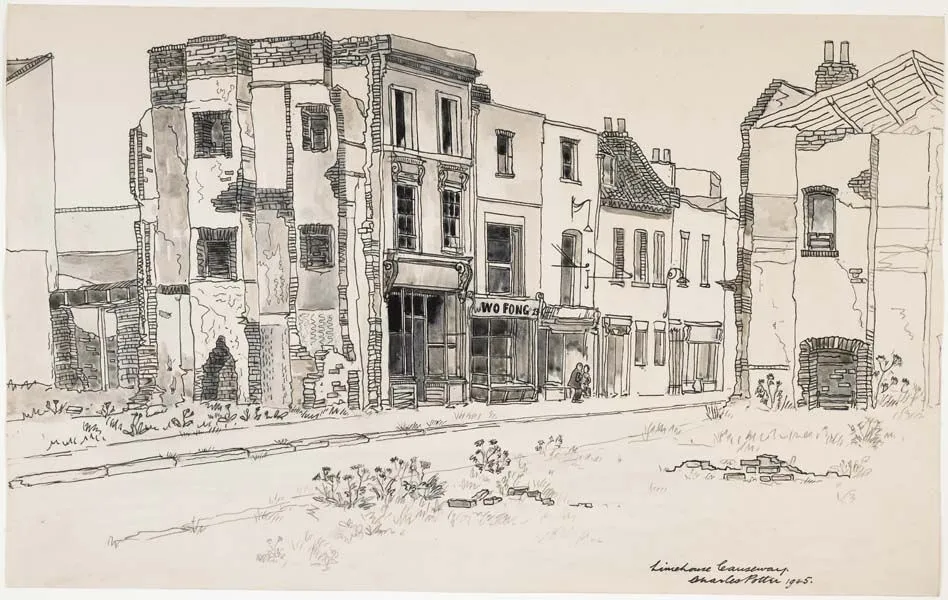

Drawing of bomb damage next to the Wo Fong Chinese restaurant on Limehouse Causeway, 1945.

Many of the old streets were also destroyed as part of slum clearance programmes, displacing Chinese communities and businesses. And later, in the Second World War, Limehouse and the surrounding docklands were badly bombed during the Blitz, forcing more families to move to the suburbs or the West End.

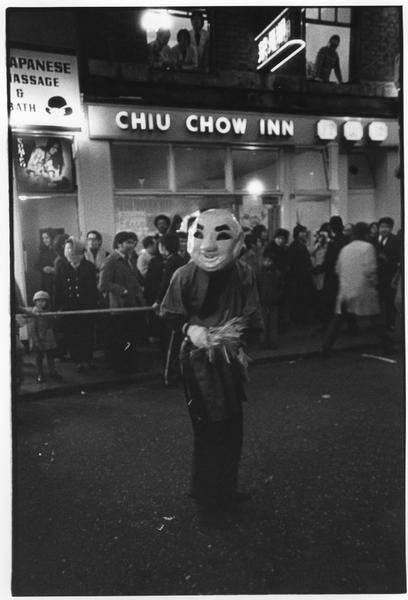

Around the same time, another Chinese community was growing on the other side of the city in Soho. By the 1970s, the West End’s Chinatown as we now know had been fully established. But the Chinatown of the East End had almost completely disappeared.