Liberty: A destination for high-quality design

Liberty is famous for its top floral fabrics and connections to artists and designers. Its historic mock-Tudor London store looks as eccentric and plush as the wares sold within it.

City of Westminster

Since 1875

A mock-Tudor treasure trove

Liberty sits right in the heart of London shopping paradise, sandwiched in between Carnaby Street and Regent Street.

It was founded in 1875 by Arthur Liberty as a small store selling products imported from countries like China and Japan. The shop soon became known for its luxurious textiles, opulent furniture and collaborations with contemporary designers like William Morris.

The Liberty building – an homage to the craftsmanship of ‘Olde England’ – has also become a London landmark. It was built in a Tudor-revival style in the 1920s, and features timber-framed overhanging storeys at the front, and cosy oak fittings and furniture inside.

Liberty looked to Asia for inspiration

Arthur Liberty, like many Victorians, was fascinated with what they called the ‘Orient’, countries east of Europe including those in South Asia, East Asia and the Middle East.

His first job was at Farmer and Rogers Great Cloak and Shawl Emporium in Regent Street. The store imported shawls from India, and Liberty was in charge of the Oriental Department. In 1875, he opened up his first shop on the other side of the road. He sold ornaments, artwork and fabrics, particularly silk, all imported from Asia. These were marketed as ‘exotic’ to London shoppers.

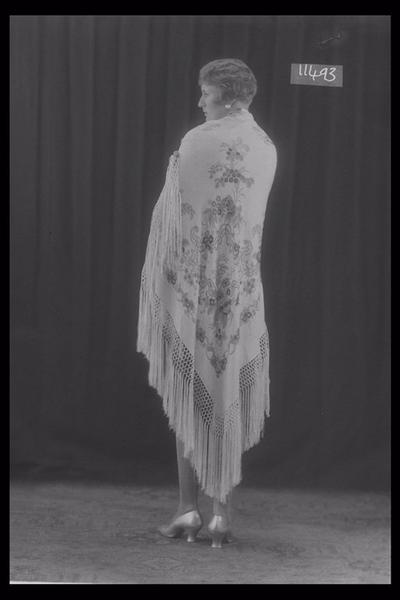

Liberty tapped into the 19th-century craze for Japanese aesthetics. The jacket above has ‘japonisme’ style floral embroidery, but a distinctly European silhouette. Although items like this were made in Japan, their Japanese motifs were tailored to British tastes. The shop also sold traditional Japanese garments, like kimonos.

As many imported fabrics were too delicate to be used for clothing or interiors, Liberty also commissioned English firms to print and dye fabrics in similar ‘Eastern’ styles. The company worked with a family-run textile producer in Merton, on the banks of the River Wandle, before buying the mills outright in the early 1900s.

Tied into British colonial trade

Liberty’s specialism in ‘Eastern merchandise’ can be understood within the context of the British empire’s expansion in the second half of the 1800s. In 1858, Japan and Britain began trading for the first time in almost 250 years.

Liberty also sold products sourced from India. He named his first shop East India House, the same as the former headquarters of the East India Company. This organisation was set up to trade with the ‘East Indies’ – the name they used for South, East and South East Asia. It later expanded into ruling large parts of India, before the British government took control in 1858. Liberty's company was part of the machinery of imperial trade, control and conflict.

The shop expanded in the late 1800s

Liberty’s first store was a success. He soon began acquiring more shop space on Regent Street. By the turn of the 20th century, the newly named Liberty & Co had broadened its range to include fashionable clothing, jewellery, wallpaper, silver and furniture. The company’s products were widely advertised and sold via their mail order catalogues.

In 1881, Liberty’s fame hit new heights as their fabrics were used in the Gilbert and Sullivan opera Patience.

From the late 1880s, the shop also collaborated with the leading designers of the day, such as Lindsay Butterfield and William Morris. Both worked in the Arts and Crafts style, which was influenced by the natural world, medieval architecture and traditional craftsmanship. Flowers, an Arts and Crafts movement staple, can be found all over Liberty’s textiles.

“I was determined not to follow existing fashion but to create new ones”

Arthur Liberty

A flagship that looked back to Tudor times

The present Liberty flagship store was built in the 1920s. Arthur Liberty had grand plans for the new space. He considered the 16th century as the height of English craftsmanship. When picturing the new space, he imagined a ship full of goods from across the world docking in the middle of London. “I was determined not to follow existing fashion but to create new ones,” he once said.

The architects came up with a lavish Tudor-style emporium which matched the ornamental, stylish merchandise sold within it. Much of the shop was even constructed using wood from two old Royal Navy ships, the HMS Impregnable and HMS Hindustan. Liberty died before his nautical dream was completed.

Liberty's interior.

While large department stores like Selfridges and Harrods opted for flashy, open-plan layouts, stepping inside Liberty makes you feel like you’re in an old, cosy manor. The carved oak fittings were handmade in their Highgate workshop. There are fireplaces, quirky wooden animals and, at one point, there was even a basement tea room kitted out to look like a castle dungeon.

Liberty’s influence on fashion

Liberty was, according to writer and regular Oscar Wilde, “the chosen resort of the artistic shopper”. Instead of being steered by garments coming out of Paris, Liberty found inspiration in artistic movements and clothes from further afield. Its distinctive textile design, particularly floral and paisley patterns, became known around the world.

In the 1960s, London designers like Mary Quant and Jean Muir used the shop’s prints in their own youth-focused fashion collections. From the 1990s, the shop expanded its collaborations with designers like Vivienne Westwood. Brands like Craig Green, Paloma Wool and JW Anderson have also launched at Liberty’s.