Joseph Merrick: 'The Elephant Man'

Joseph Carey Merrick became widely known in late-19th-century London as a human ‘exhibit’ in Whitechapel. Because of his physical disability, he was given the stage name ‘the Elephant Man’.

Whitechapel, Tower Hamlets

1862–1890

This page contains content some people may consider sensitive, or find offensive or disturbing. Understand more about how we manage sensitive content.

The London Hospital’s most famous resident

Joseph Merrick first became known to Londoners in the 1880s. He was part of an exhibit on Whitechapel Road where, because of his appearance, he was marketed to the public as being “Half-a-Man and Half-an-Elephant”. Human ‘exhibits’ like these were regarded as an acceptable form of popular entertainment in Victorian times.

Born in Leicester in 1862, Merrick’s growths on his bones, skin and other tissue got bigger over time. They increasingly impacted his mobility and made it hard for him to talk.

Like many disabled people in the 19th century, he faced discrimination, isolation and difficulty finding work. Merrick was forced to enter the Leicester union workhouse, a place where poor and vulnerable people in Victorian society worked and lived in terrible conditions.

Merrick decided to become part of a human exhibit to earn money and gain freedom from the workhouse. His life as a touring act, where his looks were exploited by showmen for profit, only lasted a few years. He later spent the rest of his life back in Whitechapel at the London Hospital.

How Merrick came to Whitechapel

In 1884, Merrick contacted the owner of a Leicester music hall named Sam Torr to become part of a ‘human novelty’ exhibition. After a few months in the midlands, he moved to a shop on Whitechapel Road under the management of Tom Norman, a successful exhibitor known as the ‘Silver King’.

Drawing of Joseph Merrick published in the British Medical Journal in 1886.

A pamphlet called The Autobiography of Joseph Carey Merrick was sold at the act, with Merrick receiving half the profits. From a first-person perspective, it describes his so-called “deformity”, tells the story of his hard upbringing at the hands of his step mother and explains his difficulties in finding work.

“I could not move about the town without having a crowd of people gather around me”

The Autobiography of Joseph Carey Merrick, 1884

We don’t know for certain how much of this was written by Merrick or his manager. But some believe this was Merrick’s attempt to claim ownership of his body. And it gives an insight into the judgement and difficulties disabled people like Merrick faced at the time. “My deformity had grown to such an extent,” the pamphlet reads, “I could not move about the town without having a crowd of people gather around me.”

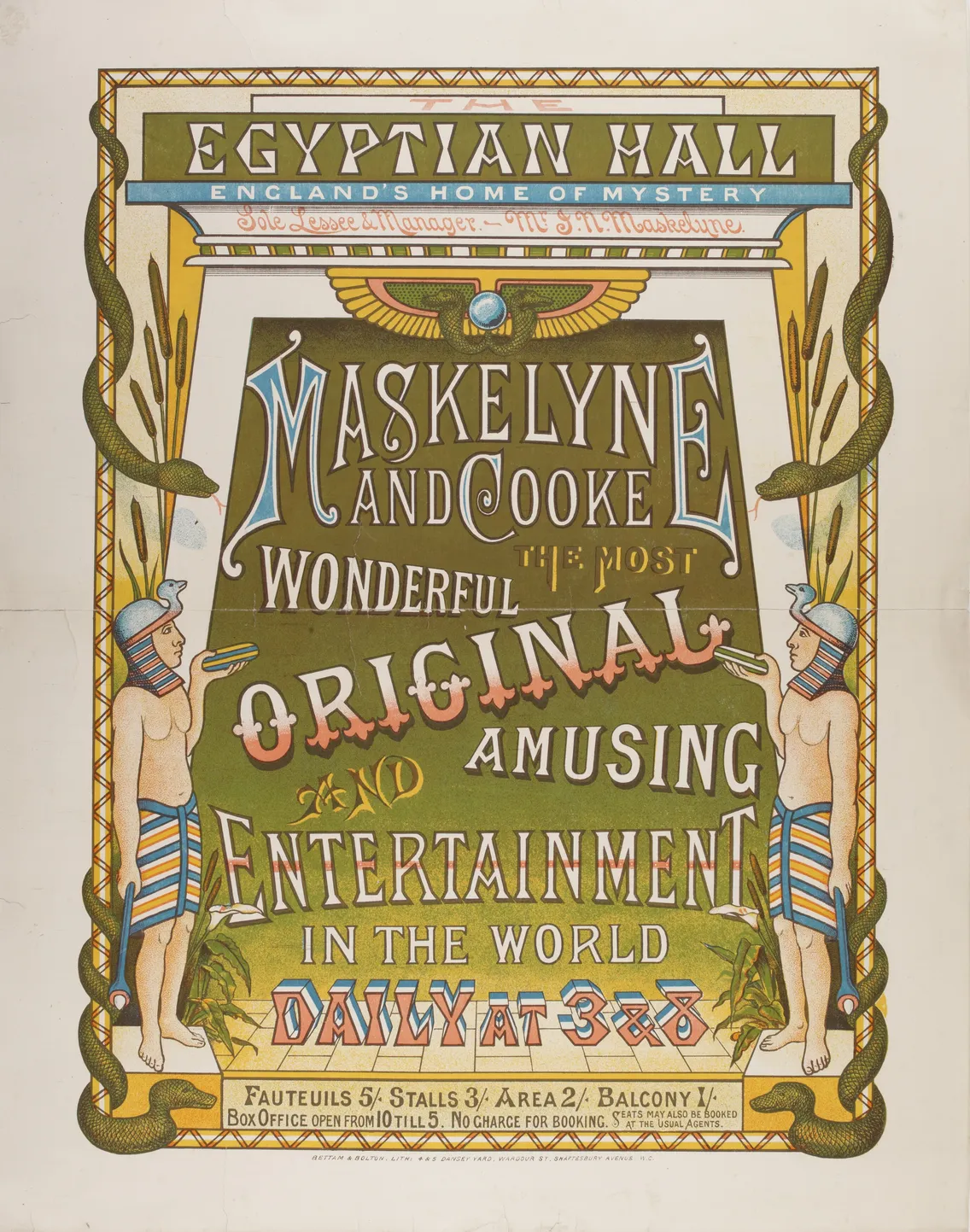

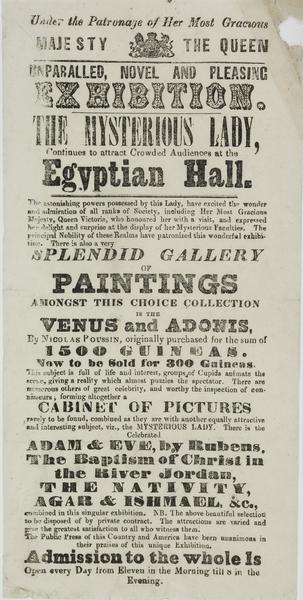

Victorian entertainment

In Victorian London, the public display of people – often those with physical differences, or bodies deemed ‘unusual’ – was considered entertainment. You can find playbills in our collection using offensive terms like ‘freaks’ and ‘curios’ to promote shows at famous venues like Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly.

These shows are rooted in the long history of the city’s fairgrounds and circuses. The centuries-old annual Bartholomew Fair in Smithfield, in the City of London, was one of the most notorious. People, including those from other continents, were put on display as early as the 1600s. English poet William Wordsworth called it a “parliament of monsters”.

The tide started to turn against these shows towards the end of the 19th century as people began to see them as exploitative and immoral. Merrick’s show was shut down by the authorities not long after it opened.

His touring life was cut short

Merrick toured Europe with a new manager and amassed savings of around £50 – over £5,000 in today’s money. But his manager robbed him of these savings and abandoned him in Brussels. This shows how vulnerable Merrick was at the hands of exploitative showmen.

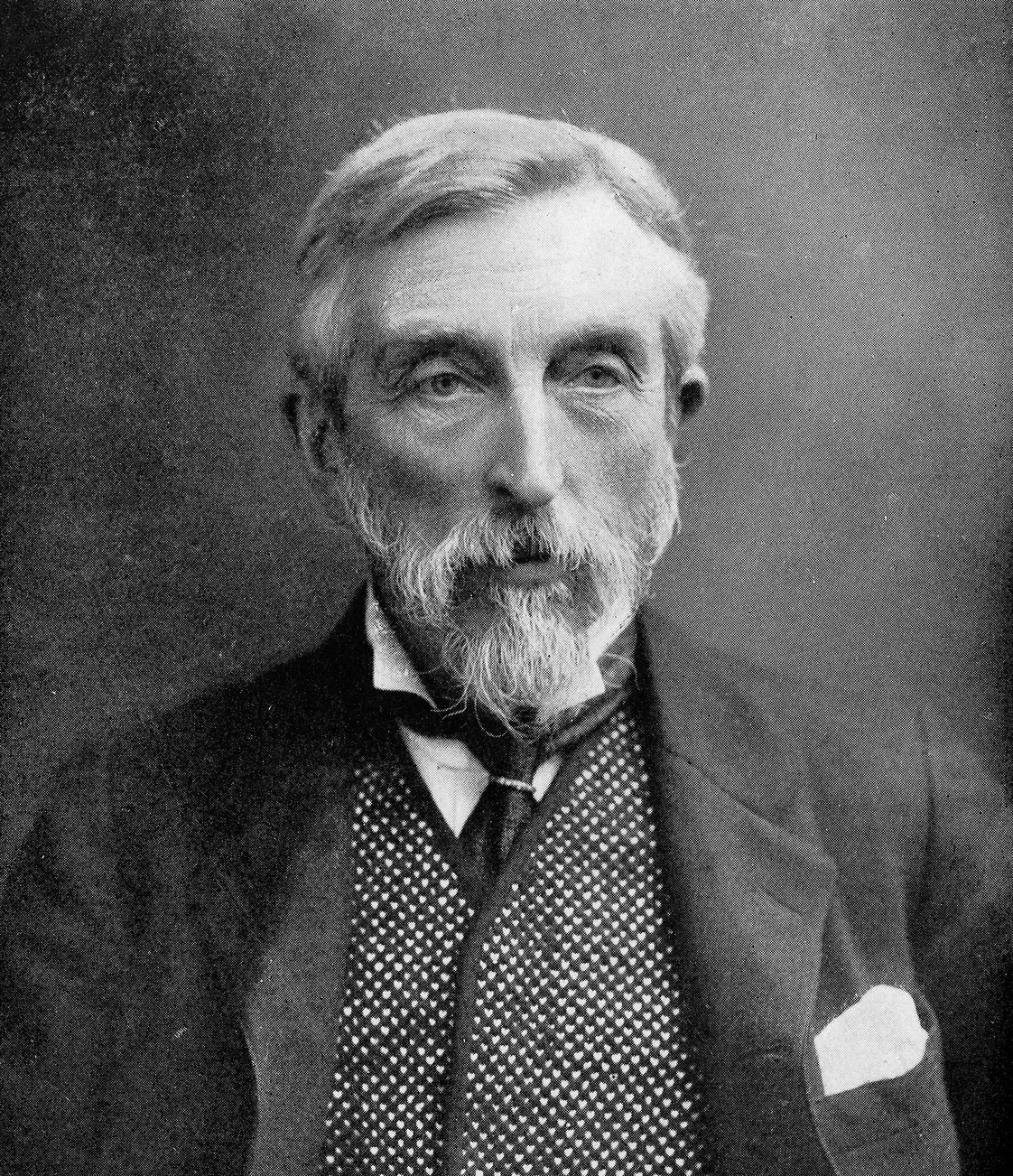

He was able to make his way back to London and in June 1886 was admitted to the London Hospital by a surgeon named Frederick Treves. Treves first encountered Merrick at the exhibition on Whitechapel Road, just opposite the hospital. Treves had himself exhibited Merrick to the Pathological Society of London in December 1882.

Living at Whitechapel’s London Hospital

Merrick spent the rest of his life at the London Hospital. An appeal in The Times raised money to convert rooms in the hospital into his own apartment.

Print depicting the London Hospital from the early 1800s.

Merrick became well known to Victorian society while at the hospital and had a new curious audience of upper-class visitors. That included Alexandra, the princess of Wales. His old manager Norman later argued that Merrick was “constantly seen and examined” and must have felt as if “he were a prisoner living on charity”. Now unable to work, Merrick would have been made dependent on the hospital’s care.

On outings from the hospital, Merrick hid his appearance from the public gaze with a floor-length cloak and a veil.

Memorial plaque for Joseph Merrick.

Merrick's death and legacy

Merrick died unexpectedly at the hospital on 11 April 1890, aged 27. Treves made casts of his body and took samples of his skin. And his skeleton was put on show at Queen Mary University of London’s medical school. Even after death, Merrick was on display and didn’t escape from an inquisitive public.

Over 130 years later, one of his biographers discovered an unmarked common grave in the City of London Cemetery and Crematorium, Newham, where the rest of his remains were most likely buried. A small plaque by the grave now marks his short life.