Joseph Grimaldi: King of the clowns

Grimaldi’s extraordinary physical comedy changed the pantomime forever – but it came at a price

1778–1837

The founding father of British pantomime

Have you ever wondered why clowns paint their faces white?

You may find it funny. Or you may find it terrifying. But this clowning tradition came from the best known performer of the turn of the 19th century: Joseph ‘Joe’ Grimaldi.

Born in London to a family of entertainers, Grimaldi was destined to be a star on the stage. He started out as an actor and a dancer. But clowning was his calling.

During the course of his career, he transformed the role of the clown from that of a rustic fool, to the central character of a metropolitan pantomime.

A new kind of clown

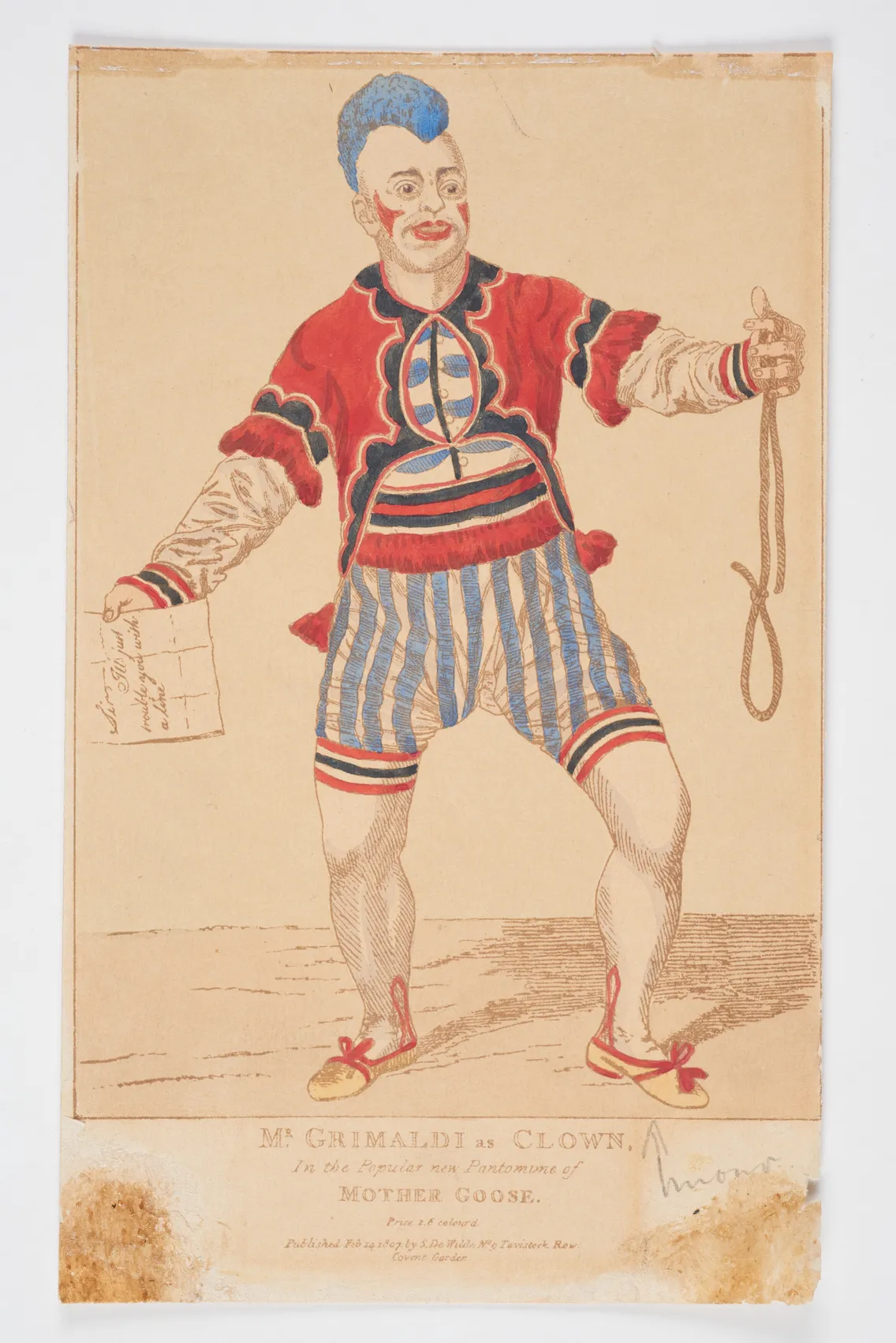

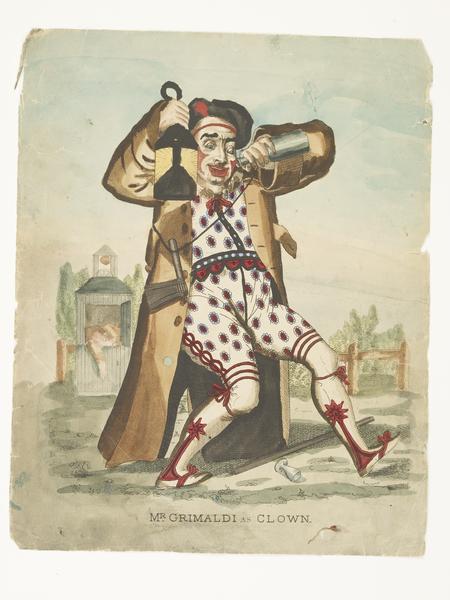

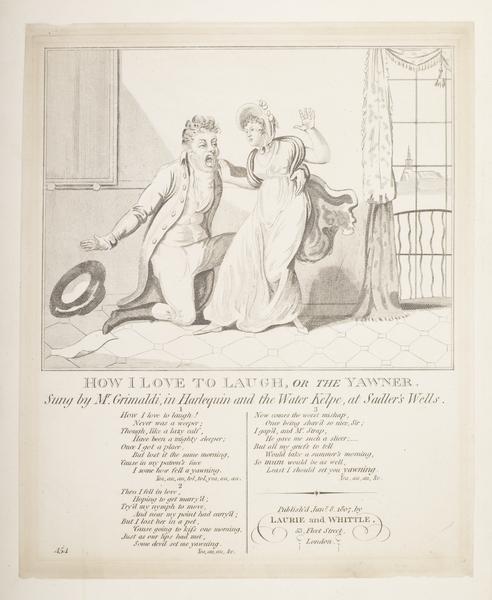

Grimaldi made his first appearance as a clown in Peter Wilkins, or, Harlequin in the Flying World at Sadler’s Wells, Islington, in 1800. Around that time, clowns wore tatty clothes with natural makeup. But the Peter Wilkins clown wasn’t like other clowns.

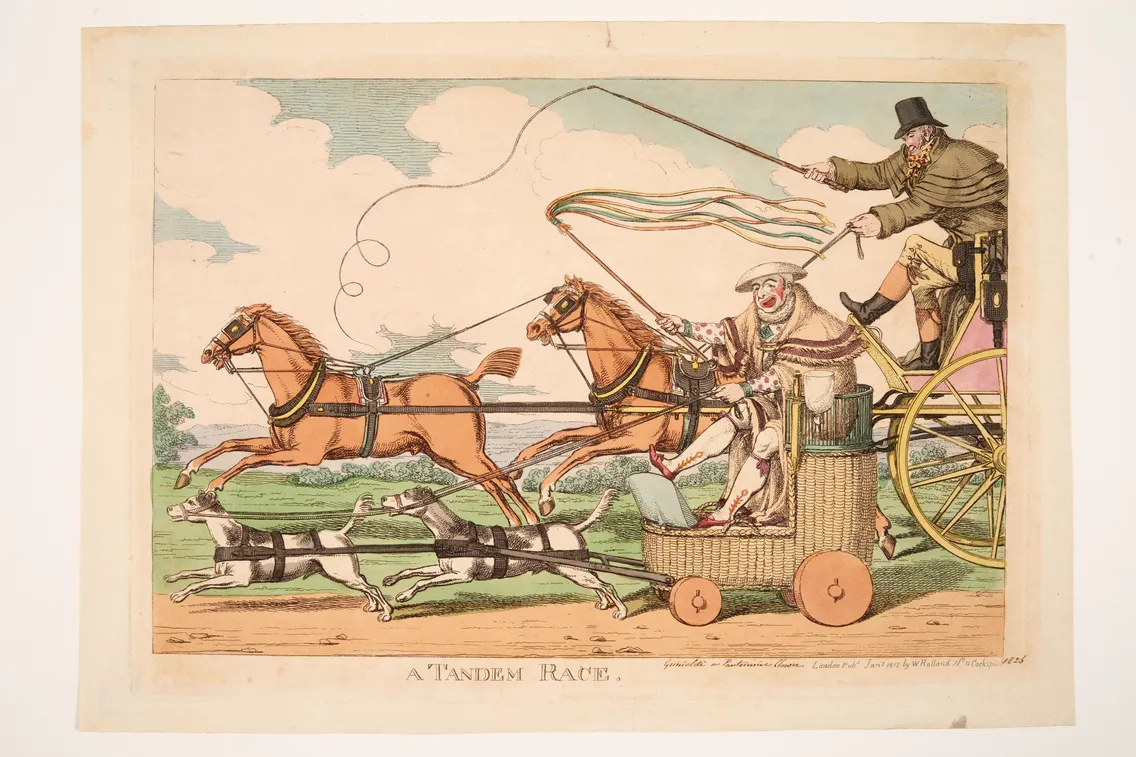

Grimaldi in the Pantomime of Gnomes & Fairies at Sadler's Wells theatre.

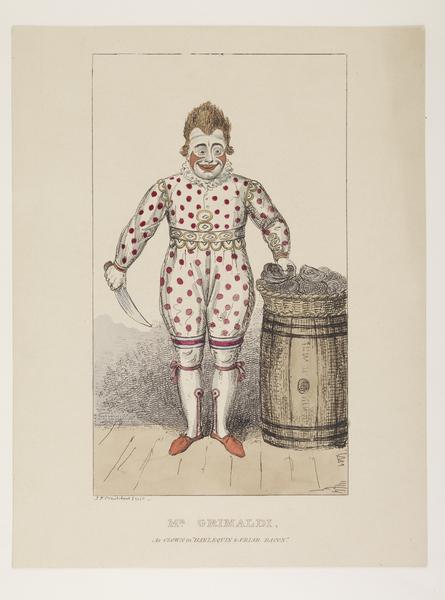

First, the pantomime broke convention by featuring two clowns, not the typical one. Grimaldi was Guzzle the Drinking Clown and the top London clown, John Baptist Dubois, was Gobble the Eating Clown. Second, the clowns were dressed in extravagant, colourful costumes. And third, it introduced a new style of makeup: white faces, with two red half-moons on the cheek.

“The modern clown was born”

Dubois left Sadler’s Wells at the end of the 1801 season. Grimaldi became the undisputed king of the city’s clowns. He was celebrated for his acrobatic skills, wild facial expressions and wicked – even devilish – activities onstage. The modern clown was born.

Transforming London’s pantomimes

Grimaldi’s clowns transformed the pantomime into a respectable and fashionable form of theatre. In the Regency era of the early 1800s, only three London theatres could have dialogue onstage – which was approved by a government censor. Pantomime had only songs and catchphrases and so was carried by physical movements. Grimaldi brought something new to this already hugely popular genre.

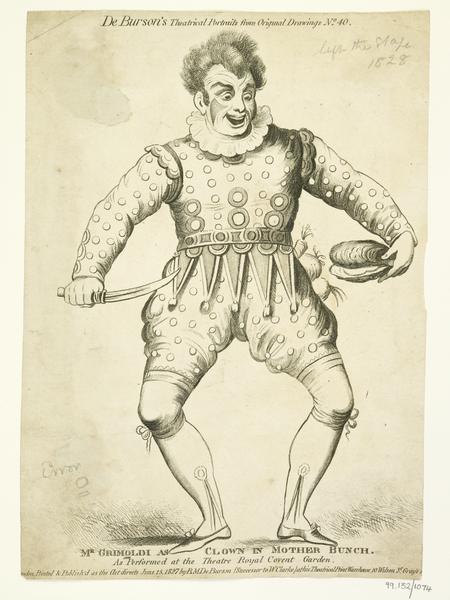

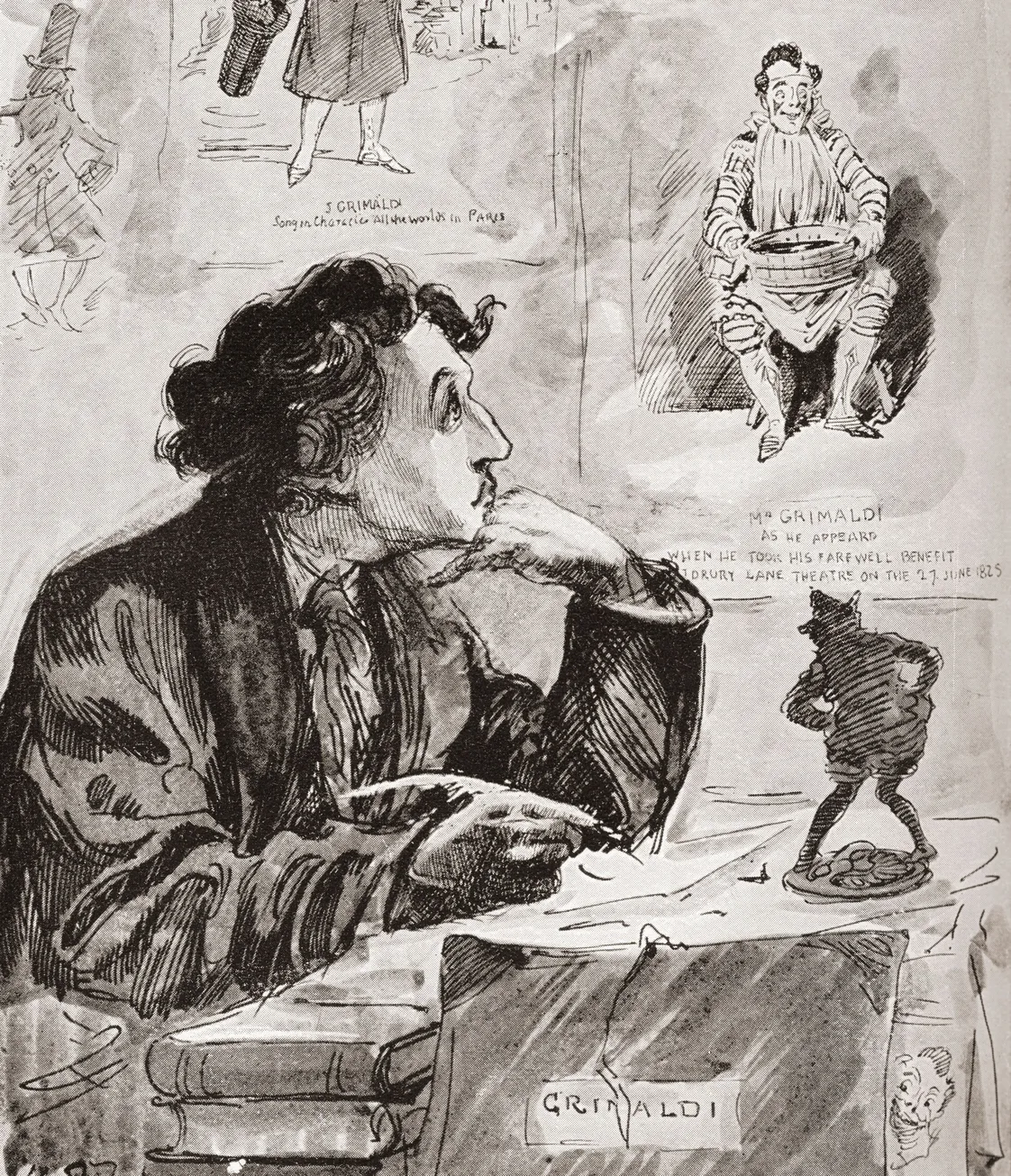

Over his 30-year career, he performed regularly at Sadler’s Wells, the Covent Garden Theatre (now the Royal Opera House) and the nearby Theatre Royal, Drury Lane – once the haunt of Shakespeare pioneer David Garrick. Audiences took home souvenir prints of him to colour in at home. And he won admirers as towering as the critic William Hazlitt, poet Lord Byron and author Charles Dickens.

“Never did I see a leg of mutton stolen with such superhumanly sublime impudence as by that man”

Lord Elron

The 1806 Christmas pantomime Harlequin and Mother Goose, or, The Golden Egg, in which Grimaldi played the sharply satirical clown, was the most successful pantomime Covent Garden ever staged. VIPs from across London travelled to see it. Politician Lord Elron said: “Never did I see a leg of mutton stolen with such superhumanly sublime impudence as by that man.”

Grimaldi’s success in London’s theatres and regional tours made him the most famous clown of his generation. He made huge sums of money – which he used to fund his extravagant lifestyle. He never kept that money for long.

Falling into poverty

Grimaldi paid the price for his intense physical comedy with his health. By 1823, his stiff joints meant he was hardly able to stand and he struggled with breathing problems. He retired from theatre that year, taking up advisory roles at Sadler’s Wells instead.

He made his final public appearances in 1828 at benefit shows held for him at Sadler’s Wells and Drury Lane. “His departure will… eclipse the gaiety of nations,” wrote The Times after the curtains closed for the final time.

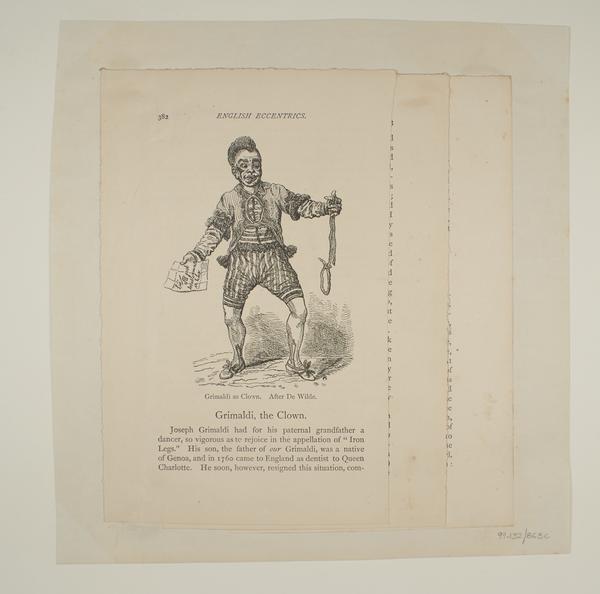

The many faces of Joseph Grimaldi.

Grimaldi fell into poverty and depression and relied on charity for the last years of his life. Joking about his struggles, he wrote in his autobiography: “I make you laugh at night but am Grim-all-day.”

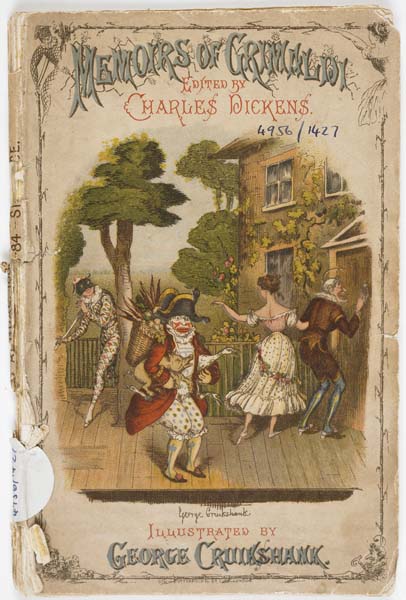

He died in May 1837. The Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi, edited by Charles Dickens and with illustrations by George Cruikshank, was published the following year.