John Hargrave: Leader of the Kibbo Kift

John Hargrave believed his Kindred of the Kibbo Kift youth movement would be a force for change in a post-First World War world.

1920–1951

Marching to a utopia

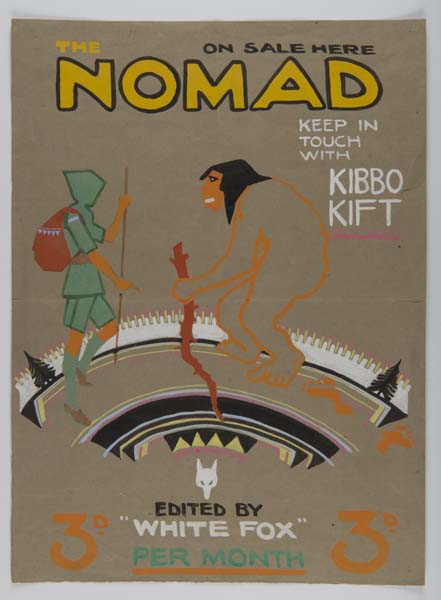

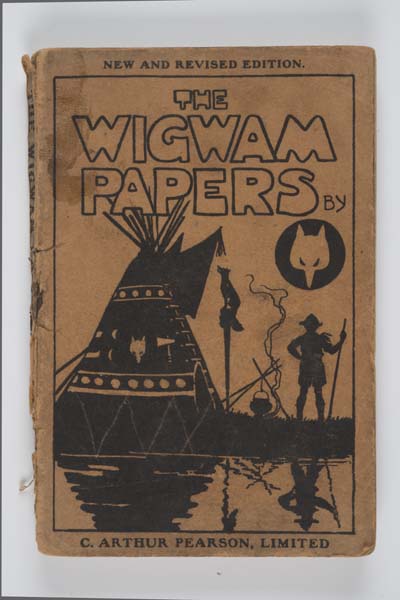

John Hargrave was a man of many talents: artist, illustrator, cartoonist, inventor, author, even psychic healer. But he’s best remembered as White Fox, the founder of the Kindred of the Kibbo Kift.

Formed in 1920, the Kibbo Kift (meaning ‘great strength’) was driven by Hargrave’s enthusiasm for handicraft and self-education. The movement began as a nature-loving group of costumed campers. But by the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, the Kibbo Kift had rebranded into a people's army who wore military-inspired uniform and marched the streets.

The Kibbo Kift grew in London, and its headquarters were always based here. Around 500 objects related to the movement – such as clothes, banners and photographs – are in our collection.

John Hargrave as White Fox, dancing with young braves.

Splintering off from the Scouts

The origins of Kibbo Kift can be traced back to Hargrave’s involvement with the Boy Scout movement. He joined aged 14 and rose through the organisation’s ranks.

But after witnessing the horrors of the First World War while serving in the Royal Army Medical Corps, he became frustrated by the Scouts’ increasing militarism. When he returned to Britain, he launched the Kibbo Kift. By 1924, it had around 500 members.

Postcard of John Hargrave in scout uniform, aged 16.

Hargrave was inspired by woodcraft ideas of spending time outdoors and developing camp skills. But unlike the Scouts, the Kibbo Kift was a pacifist and co-educational organisation. Women and girls were welcomed – including some Suffragettes.

“Hargrave believed that the Kibbo Kift could create a better society”

The Kibbo Kift’s utopian vision

Hargrave believed that the Kibbo Kift could create a better society through individual self-discipline and the embrace of an artistic, natural and healthy lifestyle. Members had to sign a declaration to:

- Camp out and keep fit

- Help others

- Learn how to make things

- Work for world peace and brotherhood

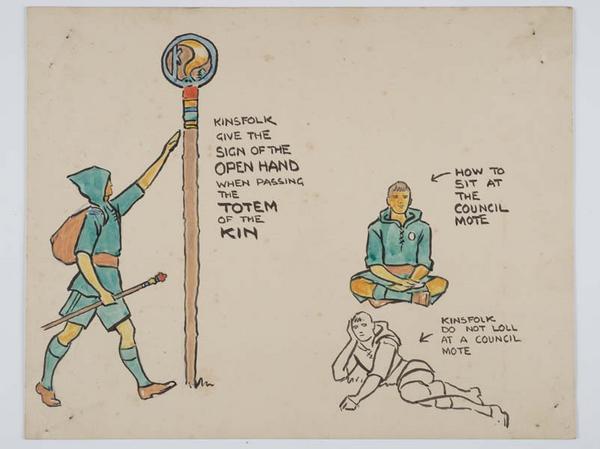

He combined this with an interest in magic. At the annual Althing, the movement’s main weekend outdoor camp, Kinsfolk made totems, put on folk plays and took part in ceremonies and rituals.

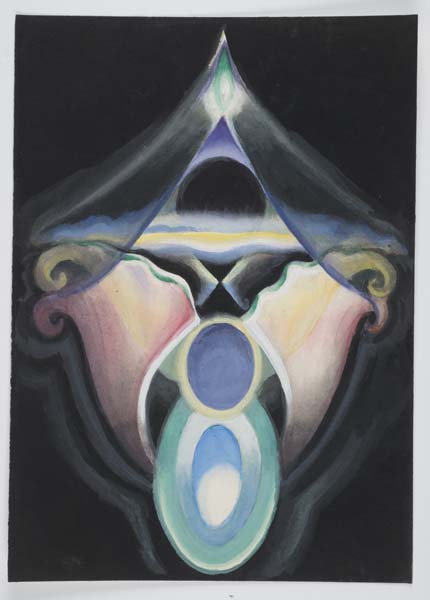

He also continued his work as an artist and illustrator defining the distinct visual style of the Kibbo Kift. Look through his drawings or the colourful badges, clothes and posters in our collection and you’ll see symbols drawn from mythology and the supernatural.

A military-inspired evolution

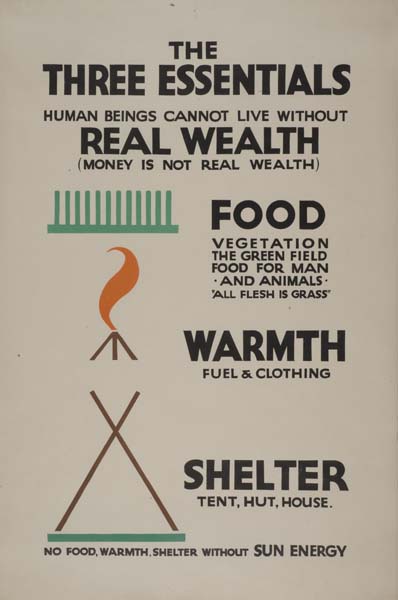

Politically, the Kibbo Kift rejected both rightwing and leftwing ideologies. But over the 1920s, Hargrave became consumed by the economic theory of Social Credit, which blamed the banking system for the existence of poverty, unemployment and war. He reshaped the Kibbo Kift to become militant supporters of the Social Credit movement.

It was an astonishing transformation. Renamed The Green Shirt Movement for Social Credit, aka the Green Shirts, the group would march through the streets spreading the word about Social Credit. They also began wearing a military-inspired uniform, which you can see on the cover of their newsletter sent out from their London headquarters.

In 1935 the Green Shirts became The Social Credit Party of Great Britain. They held public meetings, organised propaganda stunts and clashed with fascist ‘black shirts’ and communist ‘red shirts’.

The movement’s decline

The Green Shirts began to decline when the 1936 Public Order Act banned the wearing of political uniforms. The Second World War restricted their activities further. Social Credit candidates contested parliamentary elections in 1935, 1945 and 1950. But in 1951, with Hargrave’s attempts to revive the party unsuccessful, it disbanded.

After the war, Hargrave set himself up as a psychic healer, inventor and cartoonist. He earned his living as a cartoonist until his death at his Hampstead home in 1982.