The Jewish East End

From the late 19th century, thousands of Jewish families fleeing persecution in Eastern Europe transformed Whitechapel and Spitalfields into a cosmopolitan district where Yiddish could be heard on every street.

East End

1880–1914

Fleeing persecution and finding home

Between 1880 and 1914, London’s small Jewish community was transformed by the arrival into the UK of 150,000 Eastern European and Russian Jewish refugees.

Fleeing economic hardship and religious persecution, up to 70% settled in London’s East End. They swelled an established Jewish neighbourhood concentrated in the area between Spitalfields and Whitechapel. Many found work in the area’s clothing industry.

The numbers arriving caused some concern. To prevent unjustified suspicion spreading, the established Jewish community encouraged the new arrivals to integrate into British society.

Despite many arriving penniless, Jewish families who came to London improved their situation through education and hard work. Once settled, they created a vibrant community tied together by extended families.

Today the area around Whitechapel is better known for its large British South Asian population – proof that London’s story is always one of new arrivals and overlapping communities.

Why the East End?

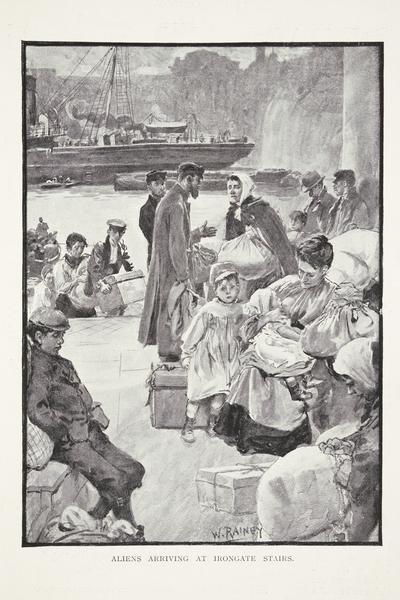

This district of London had long been associated with immigration. It was close to London’s docks and Liverpool Street Station, where people arrived after landing at the port of Harwich on the east coast of England.

The new arrivals came with little apart from the name of a relative or friend to stay with. They were encouraged to settle in the area due to the cheap housing, work opportunities and existing networks.

“571 workshops making men’s coats in less than one square mile”

How were the Jewish arrivals received at first?

The impact of mass immigration on an already overcrowded East End raised concerns among the authorities, as well as the established British Jewish community and overstretched charity workers.

To outsiders, the Jewish East End seemed like an alien “ghetto” filled with “strange exotics”. Jewish people’s language, diet and religion were unfamiliar. Crimes that appeared to be “foreign to the English style”, including the Jack the Ripper murders, were often falsely blamed on the new arrivals.

However, the Jewish East End was not a segregated “ghetto”. Jews and non-Jews lived side by side. Christian children known as “Shabas goy” were hired to light fires in Jewish homes on the Sabbath. Many non-Jewish women were hired to wash clothes and clean for their wealthier Jewish neighbours.

Mapping the community

In 1899 George Arkell was asked to create a map showing the spread of the growing Jewish community in Spitalfields and Whitechapel.

Arkell’s colour-coded map showed where Jews lived, adapting a method used on Charles Booth’s 1889 Descriptive Map of London Poverty.

The map was published in The Jew in London: a study of racial character and present-day conditions. Social reformer Samuel Barnett wrote the introduction. He hoped the publication would “do away with the prejudices which are founded either on the… jealousy of the Jews’ success or on the ignorance which is irritated at their different habits and opinions.”

He also hoped it would “dissuade any attempt to check by law the entry into England”. Just five years later, however, the government passed the UK’s first immigration act.

The 1905 Aliens Act and antisemitism

The Aliens Act of 1905 restricted immigration solely to refugees fleeing religious or political persecution. It aimed to ease fears that the Jewish people arriving were taking jobs from locals, keeping wages low and pushing up rents in the area.

Anti-Jewish sentiment could flare up in street fights. It also found an official voice in the British Brothers League, established in 1901.

But antisemitism was not a significant mass movement within the East End at the turn of the 20th century. Most non-Jews living in the East End accepted the ways of their new neighbours.

Life in the Jewish East End

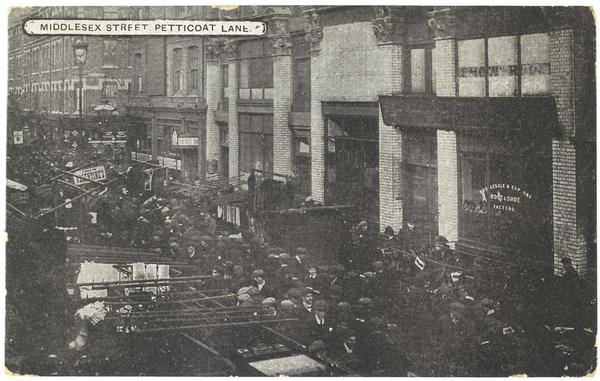

During the week, life in the East End focused on Wentworth Street or “The Lane”, which rang with the sounds and activity of Yiddish-speaking traders.

On Saturday evenings, social activity switched to the wide pavements of Whitechapel Road as Jewish families celebrated the close of the Sabbath with “the Saturday Walk”.

Although Polish, Russian and Eastern European Jews were culturally diverse, the Yiddish language was a common bond.

Jewish tailors in London

Many of those who arrived found local jobs in the clothing industry, which employed up to 70% of the East End’s immigrant workforce. By the 1880s, the industry was dominated by the “sweating” system of small workshops where labour was divided into unskilled or semi-skilled tasks.

In 1889, Charles Booth’s researchers counted 571 workshops making men’s coats in less than one square mile around Whitechapel. Most employed fewer than 10 workers, confined for long hours in cramped and steamy workrooms, an ideal breeding ground for tuberculosis.

Other Jewish arrivals worked as local market traders and shopkeepers. Jewish grocery stores, bagel bakeries and kosher restaurants thrived. By 1901 there were 15 kosher butchers on Wentworth Street.

“The emphasis was on integration”

Religion and schooling

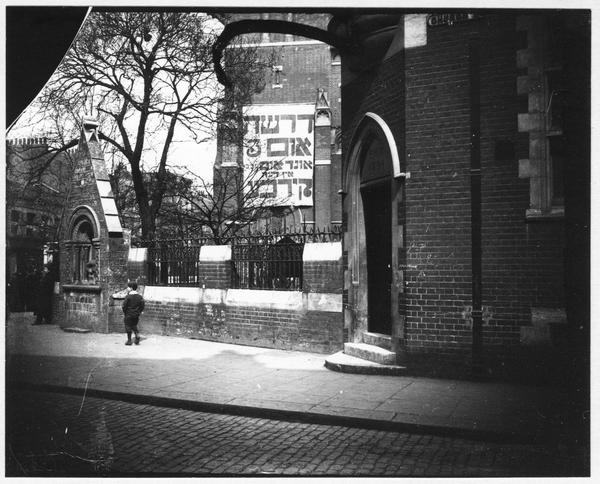

Jewish people maintained their religious traditions in self-run synagogues based on the village communities of Eastern Europe.

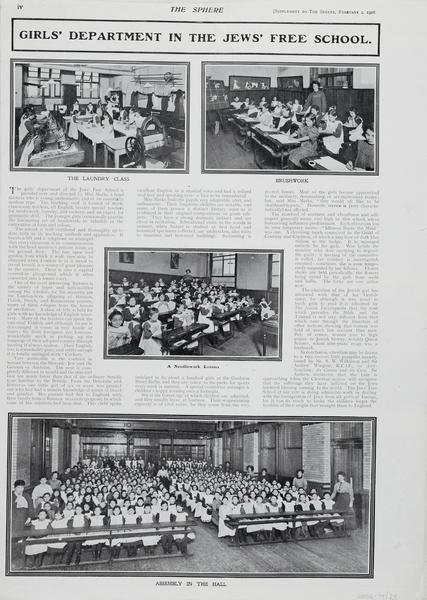

Education was seen as an opportunity to improve their lives. By 1900, the Jews’ Free School in Bell Lane had over 4,000 pupils and was the largest school in Europe. The emphasis was on integration. Pupils were encouraged to discard the Yiddish language and focus on becoming little English men and women.

Many also joined Jewish youth clubs that aimed to help young Jewish people straddle the bridge with English cultural traditions.

Images from the Jews' Free School in Spitalfields which appeared in a magazine in 1908.

Support from the Jewish community in London

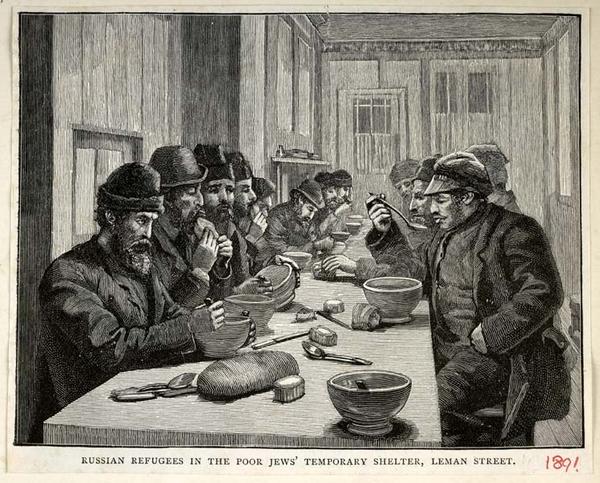

After arriving, Jewish people received help from a network of relief agencies. The Jewish Board of Guardians gave loans to buy sewing machines. The Poor Jews’ Temporary Shelter on Leman Street offered a place to stay for the first two weeks.

Wealthy British Jewish families, including the Rothschilds, supported the building of affordable housing for skilled Jewish workers.

The first tenement block built primarily for Jewish people, the Charlotte de Rothschild Dwellings, opened in 1887 in Flower and Dean Street. A second estate soon opened in Brady Street. And the Nathaniel Dwellings, housing up to 800 Jewish workers, were completed in 1892.

This is an edited excerpt of the essay The Jewish East London, 1899 published by Old House Books in 2012.