Jack the Ripper

In the autumn of 1888, a serial killer murdered five women in Whitechapel in the East End of London. The murderer was never identified, but became known as Jack the Ripper.

Whitechapel

1888

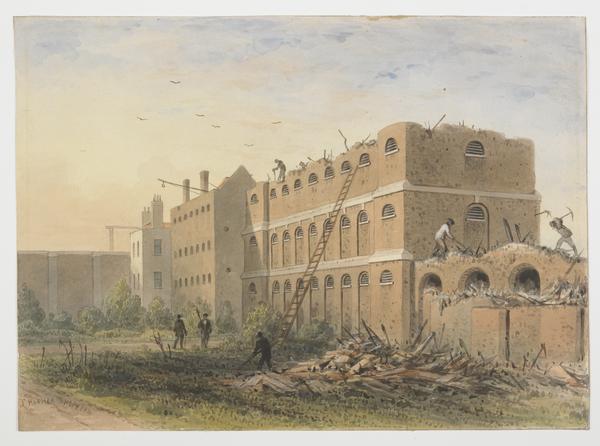

A print from the 1830s showing Whitechapel Road.

Five lives cut short

The crimes attracted frenzied attention in the newspapers, spread fear among Londoners and shocked the nation.

Speculation over the killer’s identity – often based on little evidence – has continued into modern times, making the events an infamous part of London’s history.

But this gory fascination with the murders – which are unlikely to be solved – can only tell us so much.

Recently, historians have put more focus on the lives of the women who were murdered. That helps us understand the day-to-day lives of poor Londoners living in the East End at the time, and gives us an insight into how women were judged and restricted in Victorian society.

In October 1888, the front cover of the Illustrated Police News included the murders of Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes, who were killed on the same night.

“More murders at Whitechapel, strange and horrible. The newspapers reek with blood”

Lord Cranbrook, 2 October 1888

The murders

The police investigation linked the deaths of five women to the same murderer. The women were Polly Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly.

They were killed within three months of each other – two on the same night. All of the women had their throats cut, with four of the bodies mutilated in a way which suggested the murderer had an understanding of the human body. The similarities between the attacks led to the murderer being referred to as Jack the Ripper.

Some people have linked the murders of other women in the area to the Ripper. A lack of evidence means we can’t be sure of the exact number.

Whitechapel in 1888

By 1888, Queen Victoria had been the country’s monarch for over 50 years. This was the Victorian era, a time when London had become the wealthy capital of a powerful empire. The city was modernising, but full of inequality.

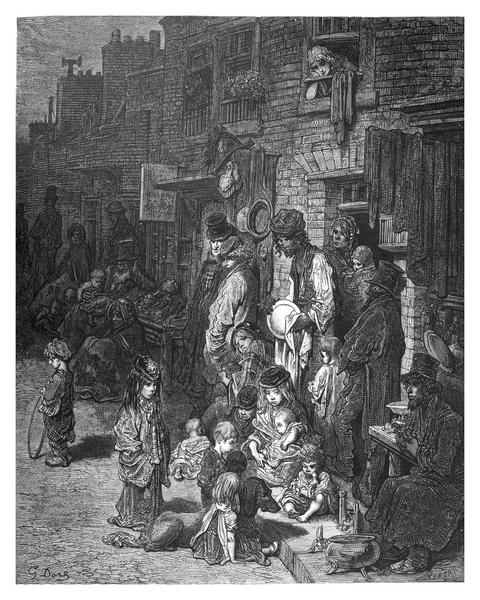

London’s wealth drew people from around the country, Ireland and Europe. There wasn’t enough housing for the city’s growing population, forcing poor Londoners to crowd into certain areas. The city’s systems for providing clean water and getting rid of waste were put under enormous strain.

Whitechapel, in east London, was one of the poorest districts. It was home to a large Jewish community, and the majority of people worked in the tailoring industry.

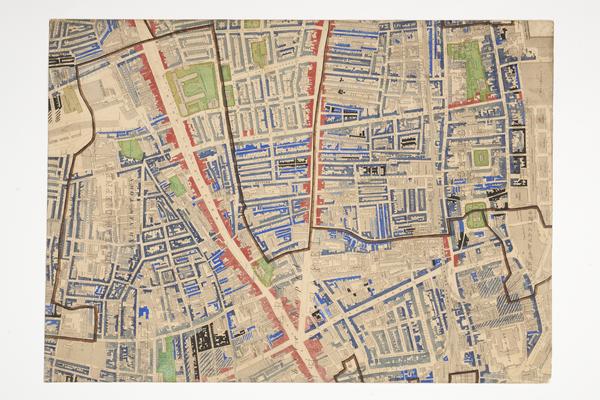

On a map created as part of Charles Booth’s study of poverty in the 1880s, Whitechapel is highlighted mainly in black and blue – the colours indicating “very poor” or “semi-criminal”.

The areas in blue and black on this map highlight the high levels of poverty around Whitechapel and Spitalfields in the 1880s.

Whitechapel was overcrowded, with some families sharing a single room. Houses were badly ventilated and damp. Jobs for unskilled workers were poorly paid and inconsistent. The intense poverty drove some adults and children into alcohol abuse, sex work and crime.

A woman walks through Hyde Park around 1895.

The women

The five women may have all lived in the Whitechapel area at the time of their deaths, but none were born there. Some were mothers. Most were born into working-class families.

They had relationships which ended through death and disagreement. And they made money in the ways available to women at the time. Annie Smith worked as a housemaid. Elizabeth Stride helped run a coffeehouse with her husband after moving from Sweden to London.

The police and journalists at the time, and many others since, wrongly labelled all of the women as “prostitutes”. Mary Jane Kelly is the only one known to have been working in the sex trade at the time of her murder.

Homeless women and those who only had enough money to live in crowded lodging houses – where they might stay for only one or two nights before returning to the street – were often wrongly associated with the sex trade in Victorian society.

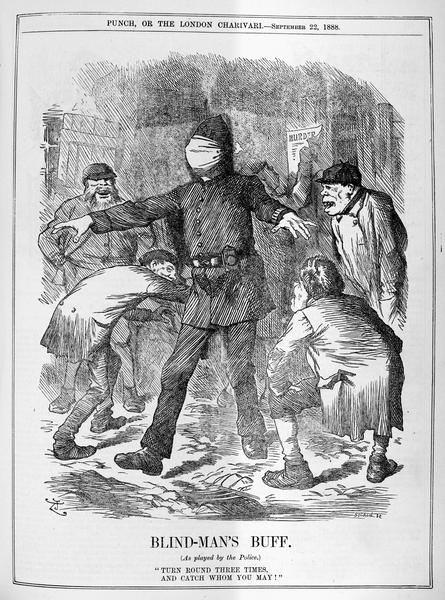

This cartoon mocks the Metropolitan Police for failing to find the killer.

The investigation

The Metropolitan Police’s detective department had existed for less than 50 years at the time of the murders. Police patrolled the area and carried out thousands of interviews to solve the crime and catch the killer.

Suspects were investigated. But the police never charged anyone.

Locals protested at Leman Street police station, demanding for the killer to be caught. A cartoon in our collection, published in 1888, mocks the police’s inability to solve the crime, showing a police officer with his eyes covered, attempting to catch a criminal.

The killings stopped after November 1888, but nobody knows why.

Antisemitic suspicion

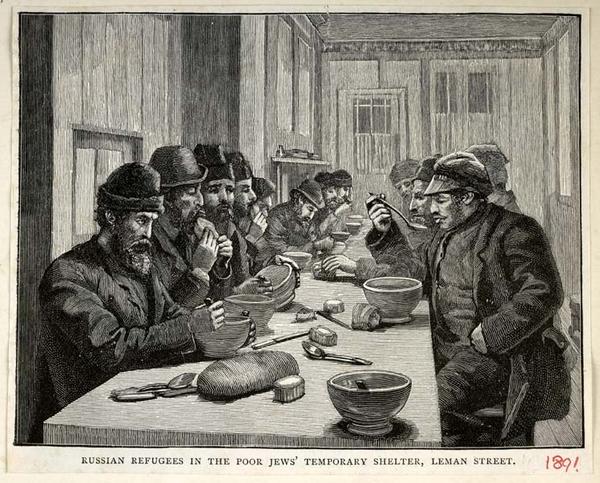

The Whitechapel murders happened at a time when thousands of Jewish refugees fleeing persecution in Eastern Europe were settling in Whitechapel and Spitalfields.

This engraving shows a temporary shelter in Leman Street, Whitechapel, which welcomed newly arrived Jewish refugees.

The unfamiliar language, diet and religion of the new arrivals – and local pressures over housing and work – made some people suspicious of Jews. They believed the murderer must have been a Jew – an antisemitic assumption not based on evidence.

Why Jack the Ripper is still talked about

The brutal details of the crimes were published by newspapers, shocking and fascinating the public. The first transatlantic telegraph cable had been laid in 1866, making Jack the Ripper’s murders an international story.

A section of the transatlantic undersea cable, which allowed the story to spread quickly to North America.

The police refused to give the newspapers information about the progress of their investigation. With the huge public hunger for more details, journalists suggested new theories. Stories became exaggerated and further from the truth. Summing up the atmosphere, the politician Lord Cranbrook wrote: “More murders at Whitechapel, strange and horrible. The newspapers reek with blood”.

From then on, the killings of Jack the Ripper became as much legend as fact – part of a classic depiction of a dark, foggy Victorian East End and its criminal characters.

To this day, books, articles and TV shows repeatedly re-examine the case, suggesting suspects and claiming to have identified the “true” murderer.